The lifespan of your new sofa may be much shorter than you expect.

Instead of once-a-decade purchases, furniture makers and restorers say, couches are becoming more like fast fashion—produced with cheaper materials, prone to trends and headed to the landfill after just a few years. High-quality sofas still exist, pros say, but they are harder to find. Mass-market options, even those that cost over $3,000, are increasingly made with less sturdy materials and construction methods.

Members of the furniture industry don’t agree on a single culprit but say the proliferation of makers, rising price of materials and our shopaholic tendencies all contribute. Expectations for a couch’s useful life now hover around seven years—and sometimes less—save for some of the most expensive models.

Consumers are complaining that their new couch’s cushions are lumpier, springs squeakier and frames flimsier than those of the well-loved models they replaced.

Ashley and Colin Lapin bought a $3,136 Eliot leather sofa on sale for $2,038 from direct-to-consumer brand Joybird in 2020 thinking it would be their forever couch. Within a few months, they say, a half-dozen buttons had popped off the tufting and discolored splotches appeared on the fabric. Worse, they say, the bottom cushions slide 6 inches forward whenever someone sits down.

“The $400 fake leather couch we got from Big Lots held up better than this,” says 40-year-old Colin, an Austin, Texas-based creative director, adding that the couple didn’t take their concerns to Joybird. “I feel a little duped.”

Joybird Vice President Gerardo Ornelas said in an email that the company is sorry to hear about the Lapins’ experience. The company has a 90-day return policy, limited lifetime warranty on foundational elements such as frames and springs and one-year warranty on manufacturing defects including loose buttons, he said.

A world of hurt

Furniture makers were inundated early in the pandemic as Covid-19 precautions kept millions of people home. Social-media posts bemoaning new furniture have shot up since then. Mentions of sofas that are low-quality, falling apart or uncomfortable were up 19% in 2023 across platforms including Twitter, YouTube and Reddit compared with 2020, according to analytics company Sprout Social.

Melissa Newell and Jennie Fisher spent $1,945 on an Eddy reversible sectional from West Elm in 2021 to upgrade their work-from-home setup, since Fisher often works from the couch.

“It is coming apart at the seams,” says Newell, a 54-year-old nurse anesthetist in Birmingham, Ala. Photos reviewed by The Wall Street Journal show misaligned edges with staples poking out, dented back cushions and pilled fabric.

“We could have spent less and I think gotten something of equal quality,” Newell says.

After months of research, Philadelphia-based government content strategist Tamar Fox thought she had found the holy grail with her $2,457 sofa from BenchMade Modern, a direct-to-consumer furniture brand. Within 18 months, she says, springs started poking out the bottom.

“I’m just so frustrated and annoyed,” 39-year-old Fox says. “The fact that I have to decide on a new couch three times a decade is ridiculous.”

Michelle and Ted Glogovac say they are disappointed with the $2,200 Thomasville Rockford sectional they bought from Costco in late 2022 to replace an IKEA three-seater they owned for 20 years.

“With the history of the brand name Thomasville, we assumed it was going to be good,” says Ted, 58, who works in aerospace sales and lives in San Jose, Calif. Instead, he says the back cushions quickly retained a permanent slump, the fabric is riddled with water stains and the chaise is indented where Michelle puts her feet.

“It looks like we’ve had it for years already instead of just one,” says Michelle, a 42-year-old podcaster.

Costco didn’t respond to requests for comment. Thomasville declined to comment.

BenchMade Modern President Dan Campbell said in an email that the company discontinued the Riley model Fox purchased. “We take pride in the quality of our products, as well as how we always put our customers first,” Campbell said, adding the company offers a warranty that includes sofa framing and suspension.

A West Elm spokeswoman said, “We are proud of the product that we offer, and we have seen consistent improvement in customer metrics including a decline in returns and damages.”

The inside counts

Americans have more sofa options than ever. That’s not necessarily to their benefit.

“It has become kind of the Wild West,” says Adam Rogers, an independent furniture designer in Portland, Maine. “People have to choose between the right aesthetic, quality and price. If they want all three, good luck.”

Jeff Boyer and his team of four technicians at Creative Colors International restore around a hundred sofas a year, often through subcontracts with retailers making good on their warranty programs. The most common complaints he hears are about flaking leather, fractured frames and pancaked cushions.

When it comes to leather, consumers often don’t know what they’re buying, says Boyer, who is based in Frisco, Texas. The “genuine leather” touted on many mass-produced options isn’t a single skin, but a slurry of ground-up slaughterhouse scraps held together with binders and glues, he says.

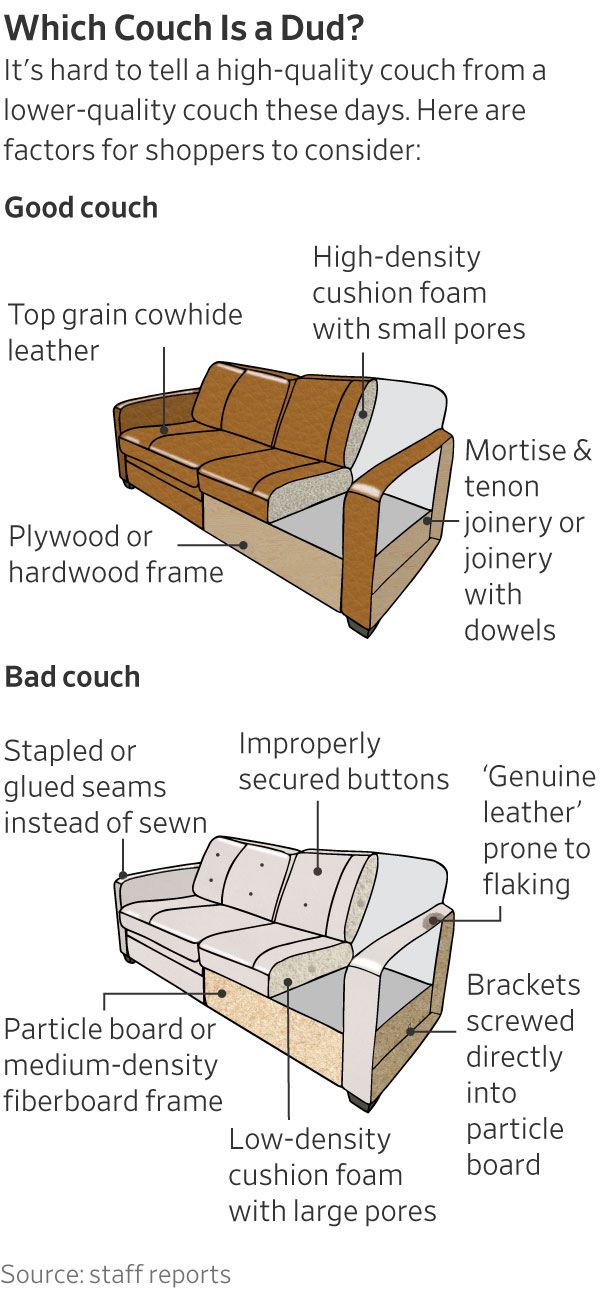

Genuine leather is the furniture equivalent of cheap cashmere, pros say. Buyers should look instead for top grain cowhide, which may darken from skin oils over time but won’t flake and fall apart.

One big advantage of older sofas is their hardwood or plywood frames, says Andy Buck, a professor of furniture design at Rochester Institute of Technology. Many newer sofas use particleboard or medium-density fiberboard, which Buck describes as compressed wood chips mixed with glue.

“It doesn’t hold a screw and over time it’s very difficult to repair, especially if it gets wet,” Buck says.

The easiest way to suss out your sofa’s skeleton, he advises: Look underneath. You should be able to see if the wood pieces are interconnected with one another in what is known as mortise and tenon joinery. With more brittle couches, those connections are made with an external bracket. Wiggling the arms and backrest is also a helpful test of their stability.

Boyer says he is getting more calls to fix snapped sofas, especially when the piece has an extendible foot or backrest. “It was a rare thing before, but we are seeing that happen even with some of the upper-end of furniture producers, where people are paying $5,000 or $6,000 for a sofa,” he says.

Low-density foam is one of Boyer’s biggest pet peeves. Fifteen years ago, cushions tended to retain their shape and comfort for a decade, he says. Now, homeowners ask him for help swapping out the innards in as few as three years.

Beyond the expense, more sofa replacement also comes at an environmental cost. American households are producing far more bulk waste than they once did, waste collectors say.

Buck at Rochester Institute of Technology says consumers could be better off spending a few thousand dollars to reupholster a thrift-store find or hand-me-down. “Most often the construction of vintage sofas will be superior to what’s made now,” Buck says.

Back in Houston, Ashley and Colin Lapin say they are still looking for their sofa for life.

“If this multi-thousand-dollar couch is disposable, maybe that means you can’t buy a permanent couch anymore,” Ashley says. “Maybe we go back to Big Lots.”

Write to Rachel Wolfe at rachel.wolfe@wsj.com