Russia freed wrongly convicted Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich as part of the largest and most complex East-West prisoner swap since the Cold War, in which he and more than a dozen others jailed by the Kremlin were exchanged for Russians held in the U.S. and Europe, including a convicted murderer.

Gershkovich and other Americans left Russian aircraft moments ago at an airport in Turkey’s capital, Ankara. Russia had kept the 32-year-old behind bars for more than a year on a false allegation of espionage. It sentenced him in a hurried and secret three-day trial to 16 years in a high-security penal colony.

Moscow also released former Marine Paul Whelan, journalist Alsu Kurmasheva and Vladimir Kara-Murza , a British-Russian dissident and Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist, sentenced to 25 years in prison on treason-related charges. Russia also released a number of political dissidents.

The sweeping deal involved 24 prisoners and at least six countries, and came together after months of negotiations at the highest levels of governments in the U.S., Russia and Germany, whose prisoner, Russian hit man Vadim Krasikov , emerged as the linchpin to the arrangement.

White House officials, U.S. diplomats and personnel from the CIA had crisscrossed Europe and the Middle East looking for friendly governments willing to release the Russian spies in their custody in return for Americans held by the Kremlin.

President Biden—about an hour before he notified the world he was dropping out of the presidential race on July 21—called the prime minister of Slovenia, whose country was contributing two convicted Russian spies to the swap, to secure the pardon necessary for the deal to proceed. CIA Director William Burns traveled to Turkey last week to meet his counterpart there and finalize the logistics for the swap.

At the center of the deal was Krasikov, a convicted murderer that Russian President Vladimir Putin had been pushing to free since 2021. The former intelligence officer, a veteran of the Soviet-Afghan war, had shot and killed a Chechen rebel leader in a Berlin park, and was serving a life sentence.

The exchange is emblematic of a new era of state-sponsored hostage-taking by autocratic governments seeking leverage over rivals. It was negotiated as tensions soared between Russia and the West over the war in Ukraine .

It also offers sobering evidence of the asymmetry between the U.S. and Russia in this new, piratical order. Putin can order foreigners plucked from restaurants and hotels and given lengthy prison sentences on spurious charges—something an American leader can’t do.

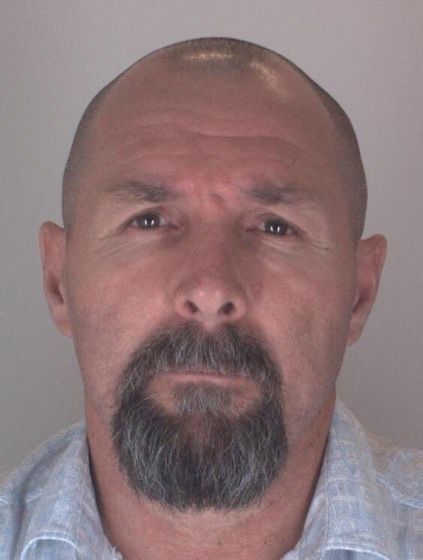

An undated picture obtained by Reuters shows Russian hitman Vadim Krasikov who was sentenced to life in 2021 for the assassination of a Chechen-Georgian dissident in a Berlin park, in Berlin, Germany, August 1, 2024. Picture obtained by REUTERS

As the U.S. sought over the course of a year to extract Gershkovich, Whelan and others without offering Krasikov in return, senior Russian intelligence officials had made clear there was no deal without him. German officials eventually agreed, extracting their own price of a dozen Russian prisoners in return.

The Biden administration has pursued a series of large prisoner swaps with hostile countries, including last year extracting 10 Americans and a fugitive from Venezuela and a major deal with Iran in which the U.S. released billions of dollars in frozen revenue. Critics have questioned whether such deals encourage the arrest of more Americans.

Biden’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, said in an interview that the president “is willing to take the hard decision to make sure that you get innocent people home, and they are going to do their damndest to do that, even if they have to pay a price.”

The State Department classifies a number of countries, including Russia and North Korea, as posing such a serious risk of detention that it discourages Americans from visiting. Privately, U.S. officials call them “abductor states” and fear their number will grow unless there are new measures to deter them.

The U.S. designated Gershkovich and Whelan as “wrongfully detained,” which commits the government to work toward their release.

Thursday’s elaborate swap happened five months after the unexpected death of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny in an Arctic prison camp in February. The U.S. and Germany had initially hoped that Navalny could be released in a broad agreement that began taking shape earlier this year, after Biden invited German Chancellor Olaf Scholz to the White House.

The two countries regrouped after Navalny’s death, assembling a package through paper-only draft proposals, hand delivered from Sullivan’s office to his counterpart in Germany. Officials from Biden and Scholz on down tried for weeks to overcome the logistical hurdles of such a large trade.

Putin and other officials had been increasingly vocal about doing a prisoner swap for Gershkovich and others since late last year. In a February interview with Tucker Carlson, Putin indicated he especially wanted Krasikov , who gunned down a Chechen rebel leader in broad daylight in a public park in the heart of the German capital in 2019.

Gershkovich— the first foreign correspondent charged with espionage in Russia since the Soviet Union collapsed—was detained by Russia’s Federal Security Service, or FSB, in March 2023, while on a reporting trip in Yekaterinburg, about 900 miles east of Moscow.

Prosecutors falsely said Gershkovich was gathering information about a defense contractor for the CIA. In fact, he was on assignment for the Journal. Gershkovich, the Journal and the U.S. government have all vehemently denied the accusation against him.

Gershkovich’s trial, condemned by Washington as a sham, was held in secret, and Russian authorities haven’t publicly released any evidence to back their assertions.

Gershkovich’s court appearances—during which he was often photographed smiling—became front-page news across America and Europe. Well-wishers raised banners at Major League Baseball games and Premier League soccer matches, calling for his release.

Journalists and celebrity news presenters from Carlson to CNN anchor Jake Tapper spoke out on his behalf.

Supporters received upbeat and joke-filled letters from Gershkovich, written in his 9-by-12-foot cell at Moscow’s infamous Lefortovo prison, where Soviet interrogators once tortured and murdered alleged “class enemies.”

Whelan, the longest-serving American deemed unlawfully detained in Russia, had also become a high-profile concern for Washington.

Included in Thursday’s swap also was Kurmasheva, a Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty journalist. The mother of two adolescent girls was detained last year for failing to register her American passport when she entered Russia on a visit to her ailing and elderly mother.

Russian authorities opened a new criminal case against Kurmasheva, a dual U.S.-Russian national, in December over a book she helped edit that criticizes the Russian invasion of Ukraine. She was eventually charged with spreading false information about Russia’s military, before being abruptly convicted after a secret trial and sentenced on July 19.

Kurmasheva has denied the charges against her through her lawyer and family. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and her family say she was targeted because she is a journalist and U.S. citizen.

Her husband, Pavel Butorin, said in a post on X after her sentencing that he and his daughters “know Alsu has done nothing wrong. And the world knows it too. We need her home.”

Other freed Russians included a suspected intelligence officer who had been living undercover in Norway’s Arctic north. Poland freed a Russian-born Spanish journalist charged with espionage. The U.S. freed a Russian businessman convicted of stealing millions from U.S. companies.

Among the Russian political prisoners freed is Lilia Chanysheva, who was close to Navalny. Americans left behind in Russian prisons include Marc Fogel, a history teacher at the high school where U.S. Moscow embassy staff sent their children. He is serving 14 years in a penal colony. He was arrested in 2021 for carrying less than an ounce of medical marijuana. He said he had intended to use the drug for medical purposes to treat chronic pain.

The U.S. has sought to free him on “humanitarian grounds.” His family has said he has suffered from neuropathy and has a hip replacement making him vulnerable to falls.

Write to Drew Hinshaw at drew.hinshaw@wsj.com , Joe Parkinson at joe.parkinson@wsj.com and Aruna Viswanatha at aruna.viswanatha@wsj.com