China’s economy is struggling, but another Asian giant, neighboring India, is suddenly squarely on investors’ and manufacturers’ radar. The first two decades of the 21st century were largely the story of China’s rise. Will the next two be the story of India’s?

There are plenty of reasons for optimism. The country’s population surpassed China’s last year. More than half of Indians are under 25. And at current growth rates, it could become the world’s third-largest economy in less than a decade, having recently overtaken the U.K., its old colonial ruler, for the no. 5 spot. India’s equity market has now seen eight straight years of gains. Worsening trade relations between the West and China only helps its case.

But India’s path forward is likely to look very different—and more challenging—than China’s.

While its labor resources are, in theory, plentiful, a host of barriers still make it difficult to connect workers with employers. That makes it hard for households and companies alike to build up the savings needed for the kind of investment booms that transformed East Asian tigers like Taiwan and South Korea and lifted them out of poverty. Still-high barriers to trade are another problem, especially if India wants to become a gadget assembly hub like China.

That isn’t to say that recent progress hasn’t been impressive, or that it won’t continue. Big electronics assemblers like Foxconn and Pegatron have poured hundreds of millions of dollars into the country, and its share of global exports has risen.

Demographically, India is where China was when its growth was taking off in the 1990s. According to the U.N., almost one-fifth of the world’s 15- to 64-year-olds will be Indian by 2030. India’s age-dependency ratio—a measure of the burden of child and elderly care on households—has fallen to 47 in 2022 from 82 in 1967, according to the World Bank.

Low dependency ratios often help lift savings and investment: Plentiful workers keep labor costs for companies in check while households themselves invest excess income rather than spending it supporting children or parents.

Unfortunately, India has struggled to smooth the path into the labor force—especially for women. Only a third of India’s female working-age population was in the labor force in fiscal year 2022, according to figures from India’s Ministry of Labour and Employment released last year. That is up about 10 percentage points since 2018, but still well below the global average for low-middle income countries of around 50%, and far below China’s 71%.

Moreover, much of the improvement since 2018 is in rural, rather than urban workforce participation—little help for labor-hungry urban factories.

Hefty subsidies for agriculture and rural food aid may be one reason. A lower tolerance for traveling away from home to live and work, compared with China where many female workers live in dormitories, may be another: 45% of women surveyed by the government last year said child care and homemaking duties kept them out of the workforce.

India’s love-hate relationship with trade is another problem. Unlike China, India is a boisterous democracy. People-pleasing protectionist measures are part of the equation. According to the World Trade Organization, India had the among highest import duties globally in 2022, with an average Most Favored Nation rate of 18.1%. In comparison, China was at 7.5%, the European Union at 5.1% and the U.S. at 3.3%. Such import restrictions may be cumbersome for manufacturers reliant on importing components to assemble and export their products.

India has been investing heavily in infrastructure in recent years, and the nation’s creaky transport network has improved—for example, the average speed of freight trains has increased over 50% in the past two years, and wait time at ports has fallen by 80% since 2015, according to Macquarie. But the government is already highly indebted, which may make continued progress difficult if a big private-sector boom doesn’t lift tax revenues.

India’s public debt load stands at about 85% of GDP—second only to Brazil among emerging economies. Central government capital expenditures will rise to an almost two-decade high of 3.3% of GDP by the end of this financial year ending 2024. Sustaining that level of infrastructure build will require higher revenues, lower subsidies or a lot more involvement from the private sector.

This all makes it crucial for India to do everything it can to smooth the path for foreign direct investment, especially in manufacturing.

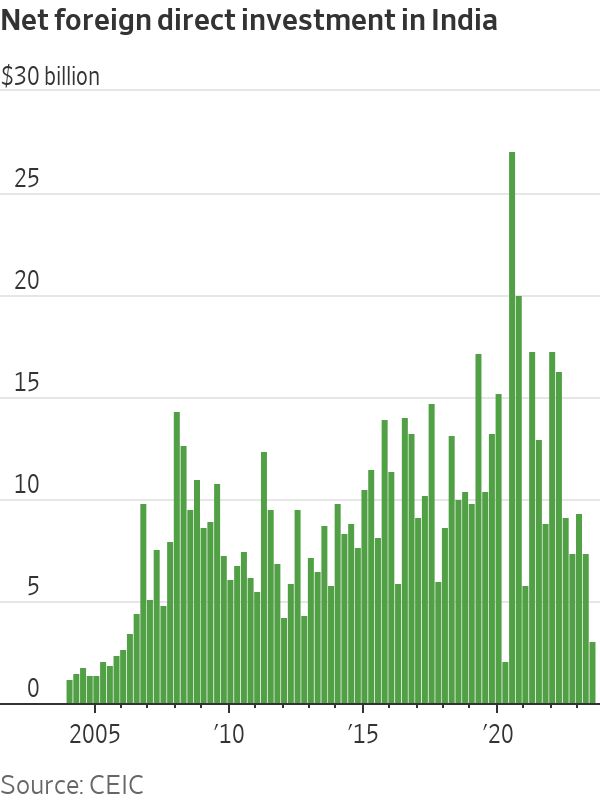

In order for India to punch its geopolitical weight, it needs outside investment to help push the manufacturing sector’s share of GDP up from below 15%, where it has been for years, to somewhere near the official 25% target. But recent signals are mixed. FDI dipped in 2022 and 2023 after hitting record levels in 2020.

Part of this decline is easy to explain: the collapse of the global tech bubble, of which India was an important part, and the general retreat in global venture-capital finance. But FDI into sectors like computers, which was equal to about 0.5% of GDP in 2021 according to HSBC, has also dropped back markedly. That is worrying because India desperately needs those labor-intensive assembly jobs. Electronics giants like Foxconn are investing heavily, but are also contending with inflexible labor laws, among other issues.

For now, at least, India remains a primarily consumption and services driven economy. Unless it can truly supercharge manufacturing FDI—which probably means solving labor market bottlenecks and reducing trade barriers, among other tasks—it may struggle to match the ferocious takeoff trajectories of the onetime Asian tigers and dragon.

Write to Megha Mandavia at megha.mandavia@wsj.com and Nathaniel Taplin at nathaniel.taplin@wsj.com