Europe’s car industry used to rule the world. Now they are fighting battles on every front.

At home, tougher emissions rules are forcing them to sell more electric vehicles, which are less profitable. In China, the rise of local competition is bringing the curtain down on a golden era for German brands. The latest threat is in the U.S., where President-elect Donald Trump champions tariffs .

“We really are in a time of great disruption,” said Andrew Bergbaum , co-leader of the automotive practice at consulting firm AlixPartners.

The turmoil is already leading to thousands of job losses and risks inflicting further damage on Europe’s economy, which has struggled to grow as fast as the U.S. in recent years. The car industry accounts for roughly 7% of gross domestic product in the European Union—far higher than stateside.

Volkswagen , the region’s bellwether automaker, reported record profit last year, but its stock now trades close to 14-year lows. It is even holding talks with its powerful union about closing factories in Germany for the first time. This week, VW workers held a so-called warning strike in protest .

VW isn’t alone. On Sunday, Europe’s second-largest carmaker Stellantis said its hard-charging Chief Executive Officer Carlos Tavares would quit , amid mounting tensions with suppliers and politicians. Last month, Ford’s European operation announced 4,000 job cuts. Big industry suppliers such as Bosch and ZF Friedrichshafen are also laying off thousands of workers each.

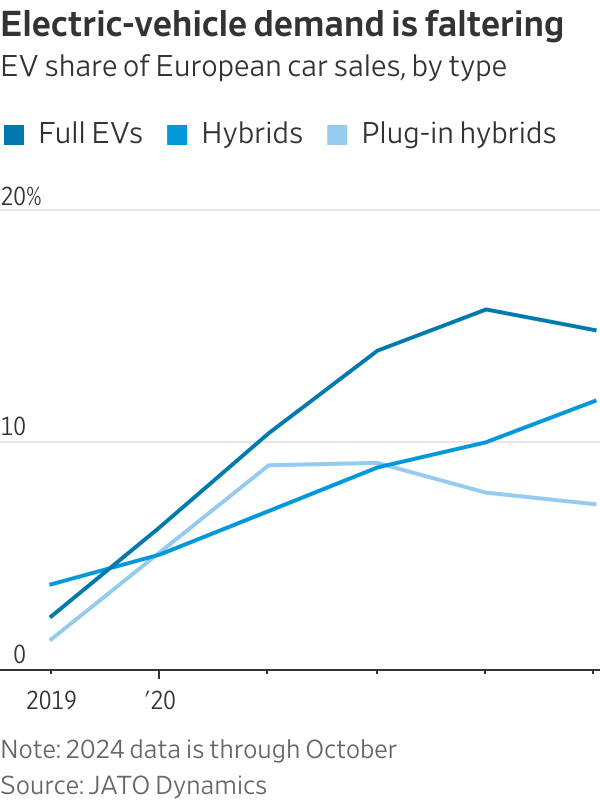

European carmakers planned for a rapid adoption of electric vehicles, spurred by regulators. But after an early burst of enthusiasm, consumers haven’t cooperated, wary of high prices and patchy charging infrastructure. Subsidies were withdrawn last December in Germany, hitting Europe’s largest EV market hard .

Starting next year, carmakers will have to sell many more EVs or hybrids in the EU to comply with new limits on carbon-dioxide emissions, or else pay fines. In the U.K., manufacturers face hefty penalties if EVs account for less than 22% of their sales this year.

VW has privately warned that it might have to pay EU fines of up to 1.5 billion euros, equivalent to roughly $1.6 billion, according to a person familiar with the matter.

The U.K. government last week hinted it could relax its rules, and some analysts expect the EU to follow suit. The uncertainty is perilous for an industry that relies on a high level of demand planning to coordinate long supply chains.

Even without the technology shift, Europe’s car industry would be struggling. Sales in the region are running almost a fifth below pre-pandemic levels after a period of high inflation that priced less-affluent buyers out of the new-vehicle market.

Production costs have been rising, particularly in Germany, which lost its supply of cheap Russian gas amid the war in Ukraine. This year, the combined profit of VW, Mercedes-Benz and BMW is expected to fall by a third. Analysts see only a modest recovery next year.

Another challenge is rising competition in Europe from Chinese EVs, which are often cheaper. While additional EU tariffs this year have slowed the European expansion plans of companies such as BYD, the policy is encouraging them to build new factories in the trade bloc.

Exports, a traditional strength of Europe’s luxury carmakers, aren’t making up for a smaller, more crowded home market. S&P Global expects vehicle shipments from Europe to total 2.7 million this year, 16% lower than in 2019.

China has long been a lucrative export market for top-of-the-range cars, but this year demand has been hit by a broader slowdown in luxury spending. Mercedes-Benz and BMW issued profit warnings in September, citing the weak Chinese market among other reasons.

It could get even worse: China has floated extra taxes on imported gasoline vehicles as a potential response to the EU tariffs.

Trump, too, has said he would introduce tariffs. This isn’t just about shipments from Europe: VW, Audi, Mercedes-Benz and BMW also manufacture products in Mexico for the U.S. Last week, Trump said he would impose a 25% tariff on goods imported from its southern neighbor.

Today’s plight is a dramatic turnaround for an industry that was an outsize winner from the falling trade barriers of the 1990s and 2000s. Europe emerged from the 2008 financial crisis with a global lead in the car in production and technology.

Even after China took the production crown, Europe’s car industry remained robust, accounting for almost a quarter of global light-vehicle output in the years before the pandemic. This year, its share is expected to fall to 19%, far behind China at 33% and not much above North America, according to S&P Global’s forecasts.

Meanwhile, EVs have handed the technological lead to the U.S. and increasingly China. Chinese companies used to pay VW for its engine know-how; now it is paying startups Xpeng in China and Rivian in the U.S. for EV expertise.

“We had a very favorable situation in the past 30 years,” said Fabian Brandt, the Germany-based global head of automotive consulting for Oliver Wyman. “A supercycle is coming to an end.”

Write to Stephen Wilmot at stephen.wilmot@wsj.com