Three years ago, everything seemed to be going right for Blake Xu.

The 33-year-old entrepreneur and his family had built a portfolio of properties during China’s real-estate boom. His wife was expecting their first child. He had just sold an apartment, and put almost half of the proceeds into the stock market.

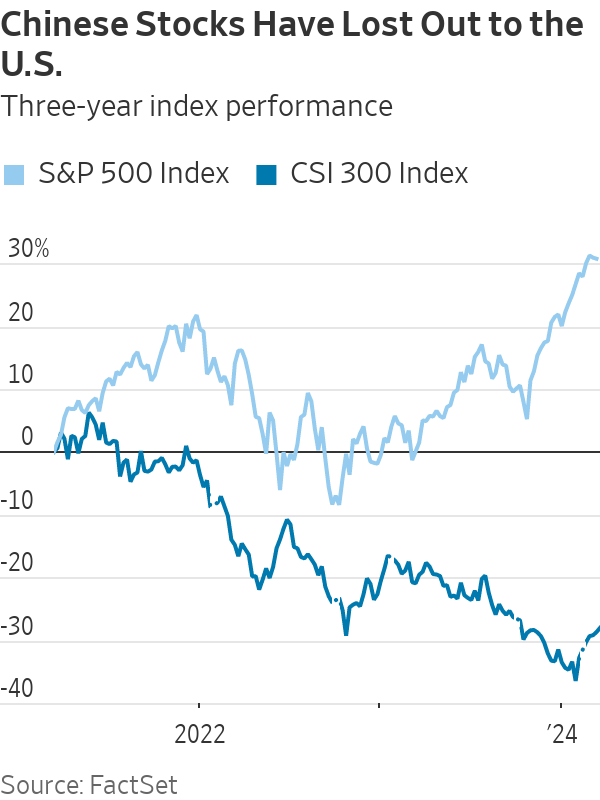

Since then, the property market has entered a yearslong downturn , the country’s benchmark CSI 300 stock index has lost around a third of its value and the economy has become increasingly vulnerable, suffering from moribund consumer confidence, weak private-sector investment and sky-high youth unemployment.

Xu has already pulled almost all of his money out of China’s stock market. His next exit may be from China itself. undefined undefined “I don’t know where the future path lies,” said Xu, who lives in Shanghai. “Once our child grows a little older, we intend to send him abroad, and perhaps we will also go.” undefined undefined For most of their lives, China’s new generation of middle-class citizens could take a booming economy for granted. But the property rout, the stock-market slump and the wider economic downturn have forced them to confront a difficult question: Are China’s boom years over for good?

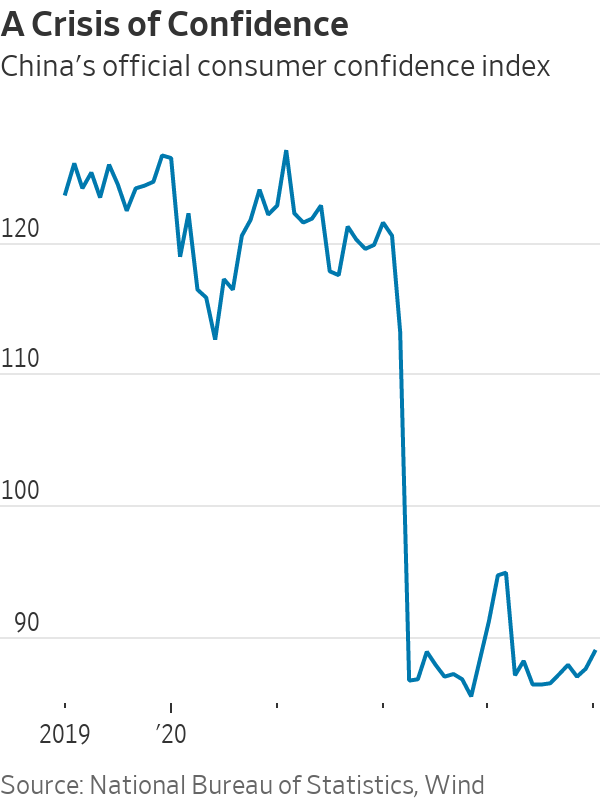

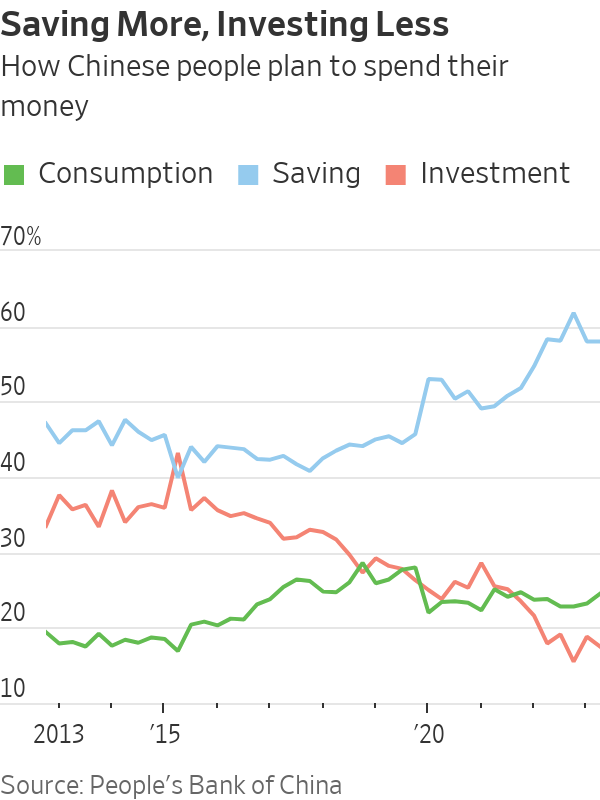

Chinese citizens are spending less, saving more and shying away from risky investments. Household savings in the country reached $19.83 trillion by February, the highest figure on record, according to data from the central bank. Consumer confidence is near its lowest level in decades.

The increasing sense of nervousness among China’s city-dwellers and white-collar workers could be a major problem for Beijing. China’s government has for years derived legitimacy from its reputation for sound economic management. undefined undefined Now, that reputation looks increasingly shaky.

Finding an exit strategy

Hugo Chen, 30, was born during the early stages of China’s remarkable economic transformation, which came after former leader Deng Xiaoping rolled back the worst excesses of Maoism and opened the doors to global trade.

Chen, who was raised in the wealthy coastal city of Shenzhen, studied for a master’s degree in the U.K. He moved back to China in 2017 to work in finance and, like many Chinese citizens, decided to play the stock market. He also bought bonds and invested in insurance products.

But last year, he made a decision: no more Chinese shares.

Chen, a banker, had previously helped an insurance company manage its money. He knew more than most about investing—and China no longer seemed like a smart place to invest money.

By the end of 2023, the CSI 300 index had fallen for three years in a row. Even worse, stocks in the U.S., Japan and elsewhere had surged. It was supposed to be China’s century , but the economy and the stock market were losing ground to those in other countries.

“Becoming poor is one thing. Becoming poor while others get rich is another,” said Chen.

He shifted most of his investments into funds that buy U.S. stocks.

China has more than 220 million individual investors, meaning stock-market moves can have a big impact on the national psyche. These small investors once had a reputation as gamblers. After the slump of the past few years, they have scaled back their bets and increasingly shifted to safer assets such as money-market funds.

The real-estate sector has done even more damage to confidence. What started as an attempt by Beijing to rein in excessive debt in the sector around three years ago has morphed into a multiyear crisis, pushing dozens of developers to the brink of collapse and pulling the rug out from under one of China’s main drivers of economic growth.

The price of existing homes in China’s most developed cities fell 6.3% in February compared with the same month last year— the biggest year-over-year decline on record .

Xu, the entrepreneur, sold a second property in a process he described as extremely painful. But he has no regrets: The money will give him the flexibility he needs to leave the country if things get worse, he said.

“Emotionally, I hope for the best for this country,” said Xu. “However, if this team of leaders stays, to be frank, I have to have an exit strategy, as the outlook is worrisome.”

That is precisely the kind of sentiment that will unsettle officials in Beijing. Although China’s government keeps a tight grip on power, it is acutely sensitive to the public mood.

China’s population has a history of public displays of dissent, including public protests against banks and companies . Beijing has tolerated at least a degree of dissent, as long as its citizens follow one overriding principle: Don’t blame the central government.

But some people in the country do blame Beijing for the current economic troubles, pointing to policy U-turns on internet companies, private education and real estate, and a strict approach to containing Covid-19 that has dealt lasting damage to confidence in the country.

The shift toward low investment and high savings is fueling a vicious cycle, where the economic slump erodes confidence levels and, in turn, low confidence worsens the downturn, said Yasheng Huang, professor of global economics and management with MIT Sloan School of Management and a fellow at the Wilson Center.

“When a society settles on a particular psychology, it’s not easy to shift,” he said.

From hope to fear

Scarlett Hu, 37, remembers how it felt to be back in China in 2014. She had just returned from studying abroad, and took a job in Shanghai’s luxury-goods sector.

“At that time everyone in the society was full of hope. There was this promising sentiment around,” said Hu. “When we went out to relax after work, we believed that tomorrow would be better and let’s have fun today.”

Hu bought an apartment in Shanghai in 2017 and started buying mutual funds that invest in the stock market in 2020, before the birth of her son. She hoped the money would help pay for his education. At the time, it seemed like a smart bet: The real-estate market was booming, and stocks were nearing a record high, cheered on by China’s bullish state media .

Her apartment has now lost 15% of its value, and her mutual-fund portfolio is down 35%.

“Now we talk about concrete plans and measures to secure a more certain future, focusing on ways to enhance our sense of security. You don’t feel that kind of ambition any more,” she said.

China’s government has taken steps to tackle the downturn, including easing lending rules for battered real-estate firms, cutting borrowing rates and pledging to resolve the debt problems of local governments. But Beijing appears reluctant to adopt the sort of direct stimulus Western governments embraced in the wake of Covid-19, when direct payments to consumers helped get spending back on track.

In early March, Chinese Premier Li Qiang said the government was targeting growth of around 5% for 2024, and there have been recent signs of improvement .

But economists think Beijing will find it difficult to hit this growth target, and some people in the country worry that things are about to get worse.

A 40-year-old equity analyst based in Beijing said she lost her job last August when the consulting firm she worked for closed. She has two children to care for, her husband’s income is unstable, and she is bracing herself for more pain to come.

“Everyone is saying that this year might still be the best in the next decade, so we should be prepared for a long period of hardship,” she said.

Write to Cao Li at li.cao@wsj.com