All those bosses still grumbling about the remote-work ethic are right about one thing: We’re working less on Fridays than we used to—some of us, a lot less.

Monday through Thursday, American work life has returned to some approximation of normal.

The rush hour is back. Offices are sort of buzzing again, especially midweek. Sometimes we even wear ties and pointy heels .

Yet in the past couple of years, the once-casual Friday slid further into work-leisure limbo land—emerging less a full-on workday and more a staging ground for the weekend. Yes, the Friday office is a ghost town, but that’s only part of it.

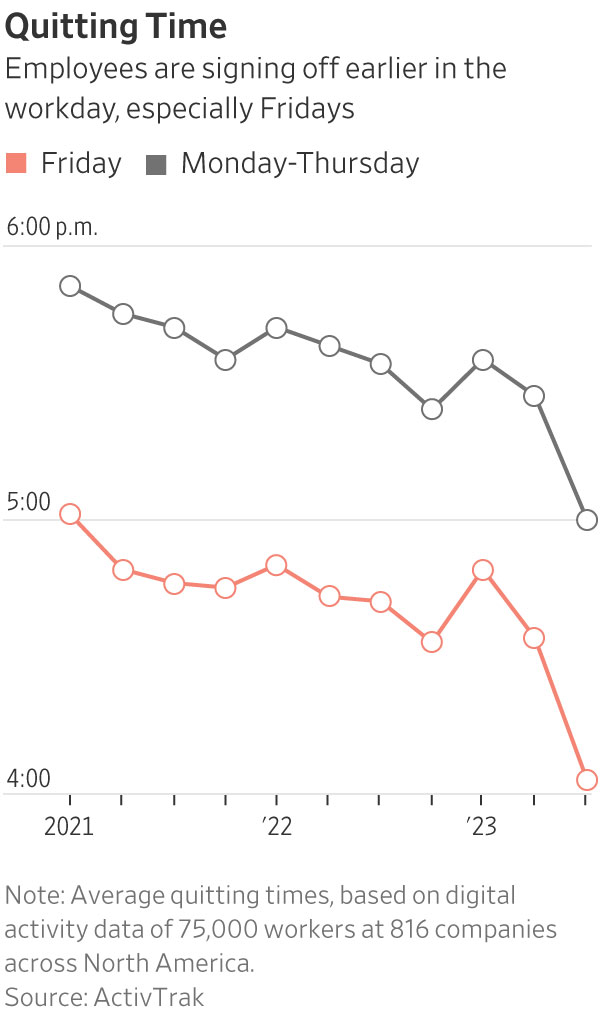

Compared with early 2021, when the remote workday often bled into evening, the average worker now signs off an hour earlier, at 4:03 p.m., according to an analysis of 75,000 workers across North America by workforce analytics firm ActivTrak. That’s also an hour earlier than the average quitting time the rest of the week (though we tend to start work a tad earlier on Fridays, too).

So why isn’t the sky falling, and worker productivity along with it? Growing evidence suggests it’s because taking it easier one day of the week can supercharge performance on others, plus mitigate the costs of worker burnout and turnover. Some bosses are even discovering their staff work more effectively when they’re left to sort their Fridays on their own.

The Friday cure-all

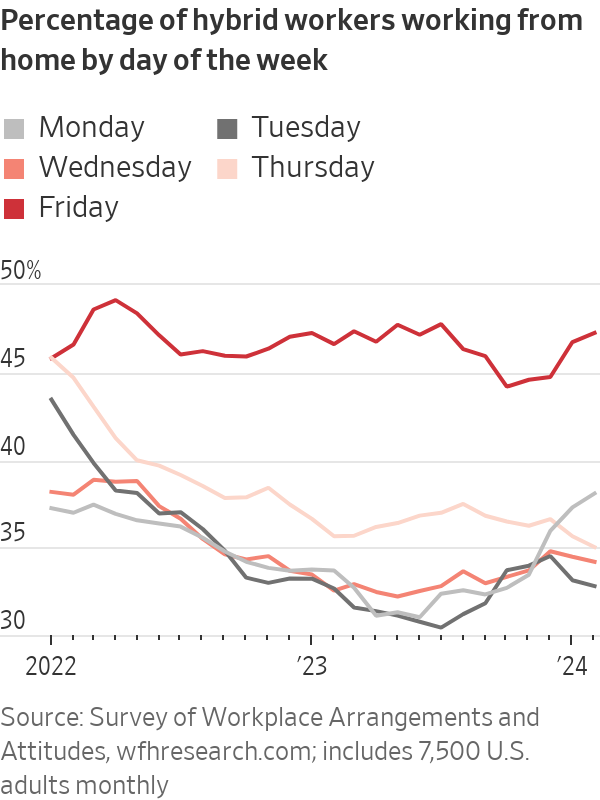

Companies have largely ceded Fridays to the work-from-home camp as a compromise.

Shorter Fridays at work are showing up in other facets of life, too. ClassPass, a subscription app that lets members access thousands of gyms, salons and spas, found that Fridays were the most popular day of the week in 2023 for scheduling wellness and beauty services. Weekly spending at restaurants used to peak at Friday lunchtime in 2019, back when work lunches were still a thing. That peak has since shifted to Saturday brunch, according to data from the Square payment platform.

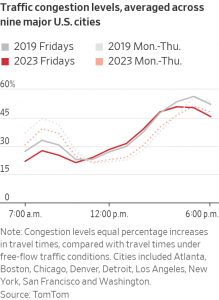

Maybe it’s because so many more people are on the road mid-Friday instead. In many U.S. cities, Friday-morning rush hour is one of the least congested times to drive during the workweek, even less so than in 2019, according to traffic data from mapmaking and location-technology firm TomTom. Early afternoon traffic, on the other hand, is even busier on Fridays as people head out sooner for weekend trips or other nonwork pursuits.

Maybe it’s because so many more people are on the road mid-Friday instead. In many U.S. cities, Friday-morning rush hour is one of the least congested times to drive during the workweek, even less so than in 2019, according to traffic data from mapmaking and location-technology firm TomTom. Early afternoon traffic, on the other hand, is even busier on Fridays as people head out sooner for weekend trips or other nonwork pursuits.

Friday, of course, was always the day we might dress down or cut out early for Happy Hour. The difference now is that it’s become a repository for all the ways we—and our employers—want to fix work life. Welcome to the meeting-free zone of Focus Fridays. Need a respite from the grind? More bosses are instituting year-round Summer Fridays as an antidote. (Meanwhile, some workers are unilaterally making them a habit.)

Freedom, not fewer hours

None of this makes Luke Liu, founder and chief executive of Albert, an interactive learning platform for grades 5-12, lose sleep over his all-remote staff’s productivity. He moved to a half-day Friday policy in 2022 to alleviate worker burnout, reasoning that Friday afternoons were the least productive part of the week anyway.

“On paper, it’s a 10% loss of time,” he says. “In reality, it’s a 2% to 5% loss.”

That lost time gets more than made up at other times with most staff, he says. Many of Albert’s 50 employees use the extra half day to take care of medical appointments and other errands, leaving more time to recharge on the weekend and to focus on their jobs during the rest of the workweek.

That lost time gets more than made up at other times with most staff, he says. Many of Albert’s 50 employees use the extra half day to take care of medical appointments and other errands, leaving more time to recharge on the weekend and to focus on their jobs during the rest of the workweek.

Letting everyone take Friday afternoons pays off in other ways too, he says. In the 20 months since Liu initiated the policy, six employees have quit—about a fifth of his staff churn in the 20 months before. “It gives back a lot of time to our managers,” he said.

There’s little doubt that lighter Fridays are tied to the greater number of people who work remotely that day, but that misses the point, says Nicholas Bloom , an economist at Stanford University.

“If you just looked naively at the days people are home, you think they’re goofing off,” he says. “If you look at the data, it’s a more complicated story.”

He points to a 2022 study he co-wrote of more than 1,600 professionals at a large tech firm weighing whether to adopt a hybrid-work model. For the six-month experiment, half the staff worked full time in the office, the rest had the option to work remotely Wednesdays and Fridays.

On their days working from home, typically one day a week, employees tended to work two hours less than the full-time office group. Many used the time for medical appointments, picking children up from school or exercise. But they made up 1.5 hours by working more over the rest of the week. They also took 15% fewer days off for sick leave and other absences, and their performance scores and promotion rates were the same as those of other workers.

“There’s no evidence that being in the office on Fridays improves productivity,” Bloom says. “There’s plenty of evidence it really annoys people.”

No more performative work

With less pressure to put in Friday facetime, virtually or in person, some workers say that’s when they do more meaningful work—even if it is a shorter day.

Staff at Super.com, an app that finds shopping discounts and other ways to save and earn money online, block off a three-hour window free of meetings every Friday to get more heads-down work done. When CEO Hussein Fazal recently analyzed how Super.com engineers use the time, he found they started 18% more coding projects—such as adding a feature or fixing a software bug—on Fridays than on other days of the week.

Interruption-free time is the key to tackling these meatier projects, says senior engineering manager Chau Duong, 34. “If you have to drop the work, it takes more time to resume,” he says.

In an internal survey, 40% of Super.com employees said they saved Fridays for their most important tasks. Half, though, said they aimed to keep their Friday workload light or use it to prep for the next week. Duong, too, says he also uses Fridays to tidy up loose ends and plan out the week ahead.

The much-hyped four-day workweek might never officially become the norm of the corporate world. But shorter, lighter Fridays appear to be how many people are creating a modified version organically.

For Sarah Ruiz, 30, who leads Albert’s customer-adoption team, Fridays are vastly different than they were several years ago. Back then, as an Atlanta-area middle-school math teacher, she’d often stay at work past 6 p.m. on Fridays, grading tests or tidying the classroom, to wait out the rush hour.

Now, on Friday mornings, she pulls together agenda notes for the coming week, or reviews where things stand with her boss. In the afternoon, she takes care of personal appointments or cleans the house. Sometimes she just watches TV or reads a book.

“It’s really about, what do I need as an individual?” she says.

Write to Vanessa Fuhrmans at Vanessa.Fuhrmans@wsj.com