KYIV, Ukraine—Ukraine fired long-range missiles provided by the U.S. into Russia for the first time Tuesday, posing a test for Russian President Vladimir Putin after Moscow’s threats to retaliate for such a move.

Ukraine used the Army Tactical Missile System, known as ATACMS, to strike an ammunition storage facility in Russia’s Bryansk region, a Ukrainian official said. The strike came just days after President Biden gave approval for their use.

“This is a signal that they want escalation,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said in response to the attack on Tuesday, describing it as a new phase in the war.

Russia has warned for months that use of such long range missiles against its territory would amount to an attack by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and lead to a clear response, but it hasn’t specified what that would be. Russian President Vladimir Putin on Tuesday signed amendments to Russia’s nuclear doctrine, in an action that appeared to be timed to send a further warning to the West.

In Washington, the White House dismissed the Russian move as more saber rattling, noting that Moscow’s revision of its nuclear doctrine had been expected. “This is more of the same irresponsible rhetoric from Russia, which we have seen for the past two years,” a National Security Council spokeswoman said.

The U.S. had warned Russia weeks ago that its use of North Korean troops against Ukraine was a “significant escalation” in the war and that Washington would respond, the spokeswoman said.

The Ukrainian Armed Forces said Tuesday that they had struck an arsenal near the town of Karachev at 2:30 a.m., causing 12 secondary explosions and detonations. The Ukrainian official confirmed that the strike was carried out using ATACMS.

The Russian Defense Ministry said its air defenses had shot down five ATACMS missiles launched by Ukraine against a military target in Bryansk region. The fragments of a sixth missile struck by a Russian interceptor rocket hit the military target causing fires on its territory, it said, but didn’t result in casualties.

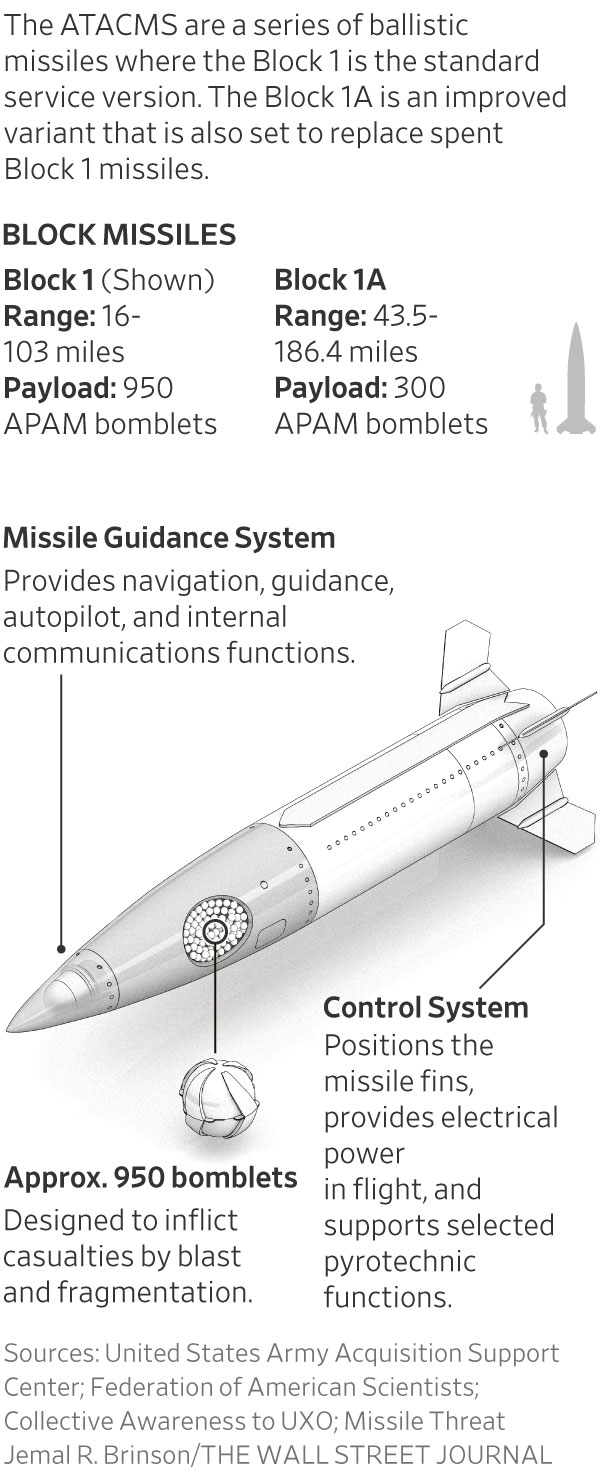

ATACMS, a surface-to-surface missile system fired from a mobile launcher vehicle, can strike between 100 and 190 miles away, depending on the model of the system.

The Biden administration had long declined to authorize Ukraine’s use of ATACMS in Russia, citing concerns of escalation . But the White House gave the greenlight after thousands of North Korean troops were deployed to Russia’s Kursk region, where Moscow has amassed more than 50,000 troops seeking to oust Ukrainian forces that seized territory in a lightning offensive in August.

Kyiv has also been calling on the U.K. and other Western allies to allow Ukraine to use other long-range weapons, such as the Storm Shadow missile. The U.K. hasn’t ruled out granting such permission. German leader Olaf Scholz has declined to send Taurus long-range cruise missiles to Ukraine despite pleas from Kyiv and pressure within his own government.

In recent months, Russia sought to head off the U.S. decision on ATACMS by warning about retaliation. Putin in September alleged that missiles as sophisticated as ATACMS can only be fired with the help of U.S. satellites and military instructors.

“If this decision is made, then it will mean nothing less than the direct participation of NATO countries—the U.S., European states—in the war in Ukraine,” he said. “And that will substantively change the very essence, the very nature, of the conflict. It will mean NATO countries are fighting against Russia.”

Despite Moscow’s nuclear threats, U.S. officials have generally been more worried that Moscow would counter in other ways, such as stepping up sabotage operations in Europe or arming Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen. Russia supplied the Houthis with targeting data as they attacked ships in the Red Sea, The Wall Street Journal has reported.

Western security officials believe Russia was behind a covert operation to put incendiary devices on U.S.-bound cargo or passenger planes. The plot was seen as part of a widening sabotage campaign that includes arson and attacks on pipelines and data cables.

Further attacks could send “a message that hostile actions on Russia’s internationally recognized territory will have a price tag,” said Alexander Gabuev, the director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

Putin has also hinted that using ATACMS against Russian territory could prompt Moscow to place more military assets in countries closer to the U.S. Russia recently sent a nuclear-powered submarine, capable of firing Kalibr cruise missiles, and a navy frigate to Cuba’s Havana harbor, 100 miles from Key West, Fla.

Russia also stepped up cooperation with Iran and North Korea. Iran is supplying drones that Russia uses to strike Ukrainian cities and infrastructure, and North Korea has sent some 11,000 troops to Russia in recent weeks, according to U.S. and Ukrainian estimates.

On Tuesday, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said Russia could ultimately deploy as many as 100,000 North Korean troops in Ukraine, where it is steadily gaining territory in the east.

Russia’s strike campaign against Ukrainian cities has intensified, but it is constrained by the number of missiles it can produce for such barrages.

The amendments to Russia’s nuclear doctrine unveiled on Tuesday are a largely symbolic move, according to analysts. The new document expands the range of threats Russia can respond to using nuclear weapons, and says an attack against Russia using conventional weapons can be a pretext for a nuclear response, including against a nonnuclear state aligned with a nuclear power, an apparent reference to Ukraine.

According to the doctrine, attacks that warrant a nuclear response are those that “pose a critical threat to the sovereignty and/or territorial integrity” of Russia or Belarus, a staunch ally where Russia also stores some of its nuclear missiles. They include use of ballistic missiles, such as ATACMS, and a “mass launch” of cruise missiles, jet fighters, or drones, which Ukraine has actively used in recent months to target Russian military bases far from the border.

Putin proposed the changes in a session of the Russian security council in September, warning the U.S. against continued support for Ukraine. “The idea was to try to find a way to limit or constrain the assistance that the West provides to Ukraine, and create some uncertainty about the possible scenarios,” said Pavel Podvig, a senior researcher at the U.N.’s Institute for Disarmament Research.

Alan Cullison in Washington contributed to this article.

Write to Matthew Luxmoore at matthew.luxmoore@wsj.com and Ian Lovett at ian.lovett@wsj.com