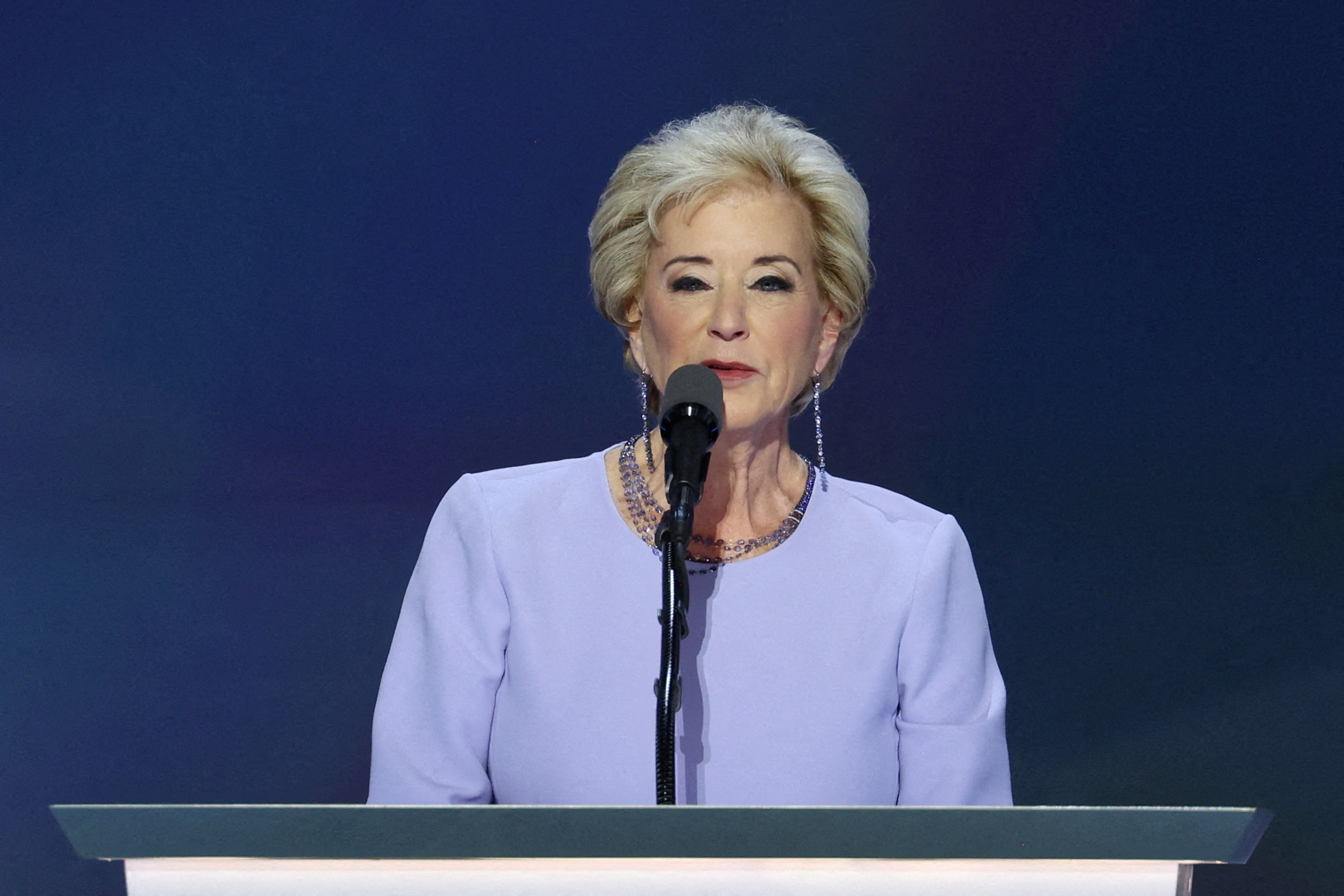

Donald Trump said he would nominate World Wrestling Entertainment co-founder Linda McMahon to lead the Education Department that he has vowed to dismantle.

“We will send Education BACK TO THE STATES, and Linda will spearhead that effort,” Trump said in a statement Tuesday evening.

The selection of McMahon as education secretary came hours after Trump picked Howard Lutnick for commerce secretary , a job for which McMahon had been a leading contender.

McMahon, a former head of the Small Business Administration in Trump’s first term, serves as co-chair of the Trump transition team. She and her husband, Vince McMahon , built WWE into an entertainment powerhouse that popularized wrestling showmen such as Hulk Hogan and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson.

She briefly served on the Connecticut State Board of Education, has supported literacy programs, including through WWE, and has been a board member of Sacred Heart University.

McMahon, who twice ran unsuccessfully for U.S. Senate in Connecticut, has said she supports school choice, tougher accountability and local oversight in education. “I believe in local control. I am an advocate for choice through charter schools,” McMahon said, according to an archived version of her 2010 Senate campaign site. She has also promoted career and technical education, according to a policy report she wrote for the America First Policy Institute, a conservative think tank that she chairs.

McMahon still needs to be confirmed by the Senate to take the position.

‘A rallying cry’

While campaigning, Trump turned the education department into a stand-in for conservative discontent with public education and federal overreach. He repeatedly called the 45-year-old agency a bloated and radical bureaucracy and vowed to eliminate it, a long-held dream by Republicans dating back to the department’s infancy.

Whether or not Trump and McMahon could actually shut down the 4,425-employee department—the smallest of any cabinet-level agency —would depend on overcoming practical and political hurdles. Some conservatives say Trump shouldn’t waste political capital doing so. Instead, they say, he should use the agency to fight left-wing ideology in schools and universities.

To close the department , Trump would have to persuade Congress. The significance of abolishing the department would depend on whether its underlying programs are eliminated too or simply moved to other agencies.

“It’s more of a rallying cry to people like, ‘Yeah they’re in our way,’” said Jeanne Allen , chief executive of the school-choice group Center for Education Reform and a former education official in the Reagan administration. “It’s a legislative challenge; it’s not about a department.”

The Education Department administers the $1.6 trillion college student-loan program. Stephen Voss for WSJ

‘Out of Washington’

Federal education funding typically makes up 10% or less of K-12 education dollars and includes money earmarked for schools with low-income students and students with disabilities.

The agency also administers the $1.6 trillion college student-loan program, investigates claims of discrimination and sets rules for improving low-performing schools, among other responsibilities. The department’s involvement in local schools is limited, though—it is legally prohibited from dictating local school curriculum or professional standards for teachers.

Trump hasn’t named major education programs that he could cut. Instead, he has made broader statements about returning education back to the states, cutting back on education spending and limiting so-called woke curriculum.

“We’re moving it all out of Washington, and we’re gonna let the states run the schools,” Trump said last month on Fox News.

Betsy DeVos , Trump’s first-term education secretary , said last week she thinks the department she once oversaw is clogged up by unnecessary bureaucracy and no longer fulfilling its mission. She said she could see an argument for shutting it down but would want support for low-income and disabled students kept intact.

The money could instead be given to states in block grants with fewer strings attached. “Shy of actually shutting it down, there are many other avenues to depower that agency and get the focus off of adults and adult issues and onto the issues they’re supposed to be serving,” DeVos said.

Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation-led conservative blueprint that Trump has distanced himself from , lays out a path toward getting rid of the department and reducing federal involvement and spending in schools. It includes ending Title I funding—which goes to schools with more low-income students—within 10 years, eliminating or block-granting many other programs and sending remaining functions to other agencies.

During Trump’s first term, he proposed merging the departments of education and labor. At another point, he tried to cut education spending, while subsuming a variety of programs into single block grants. Congress didn’t agree to either idea.

Margaret Spellings , an education secretary under President George W. Bush , said the idea of splitting up the functions over several agencies seems untenable, particularly for small school districts that would have to navigate even more bureaucracy. “What is the play that’s being run here?” she asked.

Under the Bush-championed law No Child Left Behind , federal authority in education expanded substantially. The law was eventually replaced and scaled back in 2015.

Political logistics

Completely shutting the department would require an act of Congress and likely a supermajority in the Senate.

Cutting back on federal education funding is likely to be unpopular with both Democrats and Republicans, said Patrick McGuinn , a political science and education professor at Drew University.

“The states don’t want to see that federal money go away,” McGuinn said. The 14 states that got the greatest share of their education funding from the federal government all voted for Trump this year, according to Education Department data .

Arne Duncan , who served as education secretary under former President Barack Obama , expressed dismay at Trump’s calls to ax the department.

“What’s so incredibly sad to me about all this is how much he and others have tried to politicize education,” Duncan said. “It should be the ultimate bipartisan or nonpartisan issue.”

Corrections & Amplifications undefined Trump said he would nominate Linda McMahon to lead the Education Department on Tuesday evening. An earlier version of this article incorrectly said the nomination came on Thursday evening. (Corrected on Nov. 19)

Write to Sara Randazzo at sara.randazzo@wsj.com and Matt Barnum at matt.barnum@wsj.com