SOURE, Brazil — Brazil’s military police already have a reputation as one of the toughest combat forces on the planet. But the battalion on Marajó Island at the mouth of the Amazon River has taken things to the next level. Here they patrol the streets on buffaloes.

The horned 1,800-pound beasts, which can pursue suspects across soggy mud flats and swim through thick mangrove swamps if necessary, are the only way to hunt down criminals across the vast island during the rainy season, police say.

“There are places here you can’t reach by motorbike or even boat, but buffalo, now you can always get there by buffalo,” said Sgt. Ronaldo Souza, as he saddles up Minotaur, the most formidable of the battalion’s seven water buffalo, his silky black hide gleaming under the tropical sun.

In Soure, a quiet town of some 24,000 people on the island’s northeastern tip, officers in bulletproof vests and leather boots start the day by riding the elite herd downtown to the main square, their handguns holstered.

The sight alone is enough to keep small-time crooks at bay, say locals who brag that this might be the only place in Brazil where you can wear a watch in public without fear of being robbed.

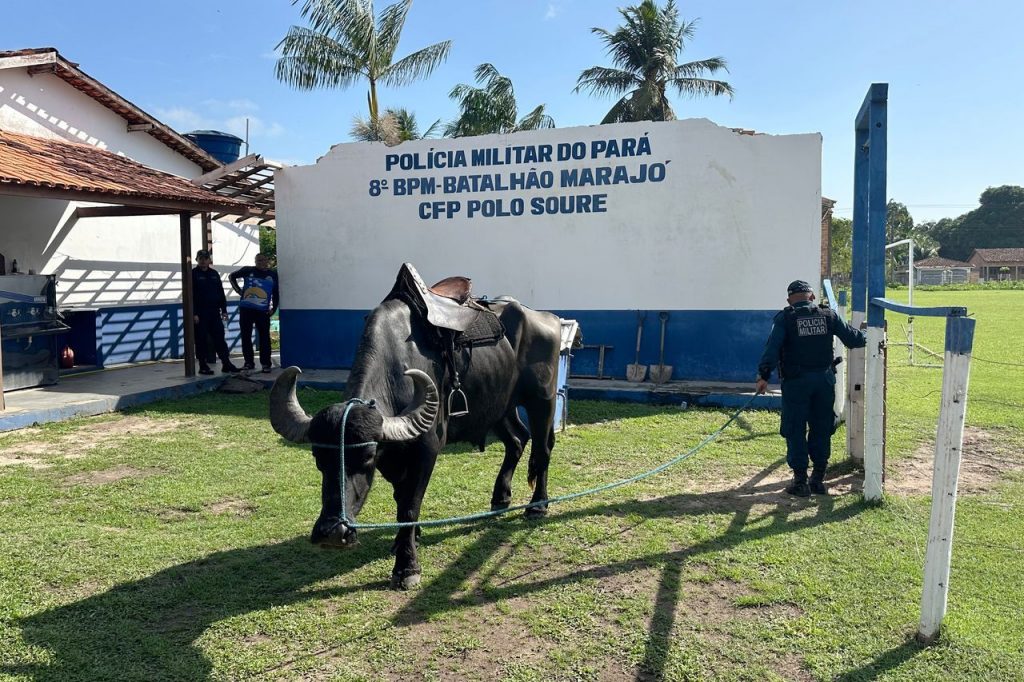

Military policemen tend to their buffaloes at their base in Soure on Marajó Island in Brazil. PHOTO: SAMANTHA PEARSON/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

While water buffaloes roam parts of South America, they are native to Asia and still a rare sight across most of Brazil. But on Marajó, a giant island the size of Switzerland where the Amazon River empties out into the Atlantic, there are now some 600,000 of them, about as many as there are people. No one really knows how they got there.

One popular legend goes that ancestors of the island’s brawny Carabao breed swam to shore in the 19th century after escaping a shipwreck. As the tale holds, the French plucked the buffalo from the rice fields of Asia and shipped them to French Guiana to provide cheap meat for their penal colony. But the boat sank before arrival.

Not to look a gift buffalo in the mouth, the people of Marajó have made every possible use of the creatures. Buffaloes now serve as Marajó’s taxis, garbage trucks and delivery vans, hauling people and goods around the island. Restaurants serve up buffalo hamburgers and creamy award-winning cheese from the milk, followed by tangy buffalo ice cream.

They lead Marajó’s carnival and independence day processions, and the island’s most beloved buffaloes even have their own Instagram pages with thousands of followers.

A water buffalo takes a break between swimming with tourists at a beach near Soure. PHOTO: SAMANTHA PEARSON/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Tourists can’t get enough of them. At one of the island’s paradisiacal river beaches, bikini-clad visitors line up to swim with the burly beasts, thrusting themselves belly-down onto the buffalo’s backs while clinging onto the loose skin around their necks as the animals glide patiently up and down the shoreline.

“Most people own dogs, but here on Marajó we have buffaloes as pets,” said Antenor Penante.

Like other islanders, he has a deep affinity for the buffaloes in his own backyard but would happily eat someone else’s. In fact, his family has spent the past three generations stripping down buffaloes’ skins from the slaughterhouse next to his home to make leather sandals.

His store’s most popular product, though, is a leather purse made from a buffalo’s scrotum. “One woman complained because she couldn’t fit her cellphone inside but I said, ‘Ma’am, there is really not much I can do about the size of a buffalo’s balls.’”

It was the early 1990s when the military police first enlisted the buffaloes. They really didn’t have much to lose, said Sgt. Idalino da Silva. “Back then, resources were tight—we had one Volkswagen Kombi van.”

A worker strips down a buffalo’s hide at Antenor Penante’s leather workshop. PHOTO: SAMANTHA PEARSON/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The cops made sure to prove their new badass credentials, commissioning a giant mosaic made of bullet casings to adorn the battalion’s entrance, depicting a muscular, red-eyed buffalo brandishing a gun.

The military police battalion in Soure has since swelled to 90 officers, most of whom now cruise around in air-conditioned patrol cars. But Souza, Silva and the other half a dozen members of the buffalo squad still pride themselves on being the battalion’s ultimate crime-fighting force.

There is one problem: there is really not much crime to fight.

Firstly, the whole island usually takes a nap from around midday to 3 p.m., which eliminates a lot of potential criminal activity in the afternoon.

Da Silva struggles to remember the last time the squad arrested anyone, recalling the last major incident a year ago when the buffalo brigade was called out to break up an argument between a husband and wife.

The most exciting thing to happen here was probably an attempted bank heist 20 years ago, they said. But on Marajó Island everyone knows everyone. Suspicious locals had already reported the newly-arrived stranger to the police, who arrested him before the aspiring criminal even set foot in the bank.

“To get away with a robbery here, you really need to come up with a good plan,” said Souza, adding that going on the run on an island was also not the smartest idea.

Members of the buffalo battalion—from left, Ronaldo Souza, Raimundo Carlos, Idalino da Silva and Jaime Serantes—line up against a mosaic made from bullet casings. PHOTO: SAMANTHA PEARSON/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

An official of the buffalo battalion leaves the military police base. PHOTO: SAMANTHA PEARSON/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The only crime that has really flourished on this buffalo-mad island over recent years is the theft of what some might say is the only thing worth stealing around here: buffaloes.

Officers took to stationing the beasts on distant farms in recent years so they could spring into action and hunt down missing buffaloes rustled off by criminals in the dead of night.

Though outfitted for the kind of urban combat common to some Brazilian cities, members of the buffalo brigade actually spend much of the day as farm hands, tending to their animals as they graze on the soccer field next to the police base.

The cops pamper them from a young age. And for the most part, the buffaloes only obey their keepers so it is up to the cops to do the work themselves. That means lathering the animals with coconut soap, deworming them and hand feeding them mangoes. The cops shush them like a baby when they get antsy.

In fact, spend a few days on Marajó and it soon becomes apparent that on an island that depends so heavily on buffaloes, it is the humans who are at the service of the animals rather than the other way around.

Marcio Alves waits while his three buffaloes finish grazing in downtown Soure. PHOTO: SAMANTHA PEARSON/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

“Mine only like to work in the mornings,” said Marcio Alves, who had been perched on his motorbike by the side of the road for three hours. It turned out he was taking his three buffalo (Lord, Goat, and Blacky) for a walk.

The trio sleep in his backyard and earn him a living by pulling around carts of construction material in the morning. But the only way to keep them sweet, Alves says, is to let them out to graze around the town in the afternoon.

“They’ll decide to go home soon,” he says, setting off again to follow them to another patch of long grass down the street. “They know the way…they’re smarter than most people.”

Write to Samantha Pearson at samantha.pearson@wsj.com