In a meeting with top Justice Department officials, Javier de Luis pressed them on Boeing : The plane maker had told the government that it couldn’t find records related to the January door plug blowout on an Alaska Airlines flight.

“You’re going to let them get away with that?” he prodded at the April meeting. De Luis wasn’t a lawmaker or lawyer—his sister, Graziella de Luis , died in a 737 MAX crash in 2019.

Weeks later, the Justice Department said the plane maker had failed to live up to commitments to improve its compliance program after crashes of two 737 MAX jets about five years ago. The move opened the door to potential criminal prosecution of the company, and marked another recent victory for families of people who perished in high-profile airplane accidents.

Families scarred by the 2018 and 2019 MAX crashes and earlier aviation disasters have channeled their grief and anger into concerted efforts to tighten regulations, craft new air-safety policy and extract penalties from companies. By sticking together for years and honing their messages into concrete requests and Beltway-ready presentations, they have become an influential force, even if their efforts aren’t always successful, according to current and former congressional officials, lobbyists and industry officials.

Families and friends who lost loved ones in the March 10, 2019, Boeing 737 Max crash in Ethiopia, hold a memorial protest in front of the Boeing headquarters in Arlington, Virginia, on March 10, 2023 to mark the four-year anniversary of the event. (Photo by OLIVIER DOULIERY / AFP)

The families of MAX crash victims fought in court to be legally recognized as crime victims, granting them meetings with prosecutors and a voice in potential punishments. At the April meeting between federal prosecutors and family members, de Luis presented a point-by-point argument as to why the Justice Department should punish Boeing.

Supporting evidence, he said, had turned up in a federal review of the company’s safety culture—a review that de Luis participated in, mandated by a law he had helped lobby for.

In mid-May, Justice Department prosecutors accused Boeing of failing to set up a robust compliance program in an alleged violation of the company’s criminal settlement agreement that followed the MAX crashes. Boeing, which can appeal the DOJ’s decision, has said it believed it met the requirements and looked forward to responding to federal prosecutors.

The dispute sets the stage for courtroom drama in Boeing’s criminal case.

Also in May, Congress cleared an aviation bill that left untouched a rule requiring most pilots to log 1,500 hours of flying time before they can fly for airlines. That requirement became a flashpoint last year as the industry grappled with a shortage of pilots.

Family members of the 50 people who died in the 2009 Colgan Air crash near Buffalo, N.Y., pushed for that requirement and opposed efforts they said would water it down. Some industry groups have countered that flying requirements lack structure, and lawmakers had proposed ways to incorporate more flight simulator time.

The MAX and Colgan families are part of a grim fraternity of grassroots advocates. The National Air Disaster Foundation, another group founded by air-crash survivors and victims’ families, is a member of government aviation rule-making bodies. Other high-profile tragedies, such as the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, have spurred advocacy groups of their own.

Ronce Almond , who until last year worked as a top Democratic aviation staffer for the Senate Commerce Committee, said the MAX and Colgan crash families are among the most effective safety advocates in Washington.

“They will continue to dog you until you at least acknowledge their position,” said Almond, who worked on policy with both family groups.

Beltway beginnings

The MAX families ramped up their advocacy a few weeks after the second Boeing MAX crash, in Ethiopia in March 2019. Among the most prominent members of the group have been Michael Stumo and his wife, Nadia Milleron , whose uncle is Ralph Nader , the longtime consumer crusader and fixture in Washington, D.C.

As the couple mourned the loss of their daughter, Samya Rose Stumo , Nader suggested they take action. Regulators around the world had grounded the 737 MAX. “They’re going to put this plane back in the air without fixing it,” Milleron recalled worrying.

American civil aviation and Boeing investigators search through the debris at the scene of the Ethiopian Airlines Flight ET 302 plane crash, near the town of Bishoftu, southeast of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia March 12, 2019. REUTERS/Baz Ratner

Milleron began helping to organize other MAX families when they were in a hotel lobby in Ethiopia waiting to visit the crash site in 2019, collecting names for a WhatsApp group.

“We want no third crash,” Stumo said.

Over the course of the next year, the MAX families lobbied behind the scenes against Boeing, an aerospace giant known for its influence in Washington. They worked both sides of the aisle as lawmakers considered overhauling how the Federal Aviation Administration approves new aircraft. At one House hearing during the pandemic, Milleron was the only member of the public who attended, sitting alone with a photo of her daughter around her neck.

The MAX families regularly secured meetings with senior FAA officials. Boeing often found out only after the fact that the families had met with officials at the company’s most important regulator, according to a former Boeing lobbyist.

“Historically, grieving families have a lot of moral authority with members of Congress,” Nader said. “They can’t stare down the bereaved families as easily as they can stare down just consumer advocates.”

The families later focused on a key pressure point—the FAA’s Boeing oversight office in the Seattle area. They viewed the acting manager of that office, Ian Won , as an independent FAA official who was holding Boeing’s feet to the fire, and their support contributed to the agency keeping Won in that role longer than expected, according to Almond and others briefed on the matter.

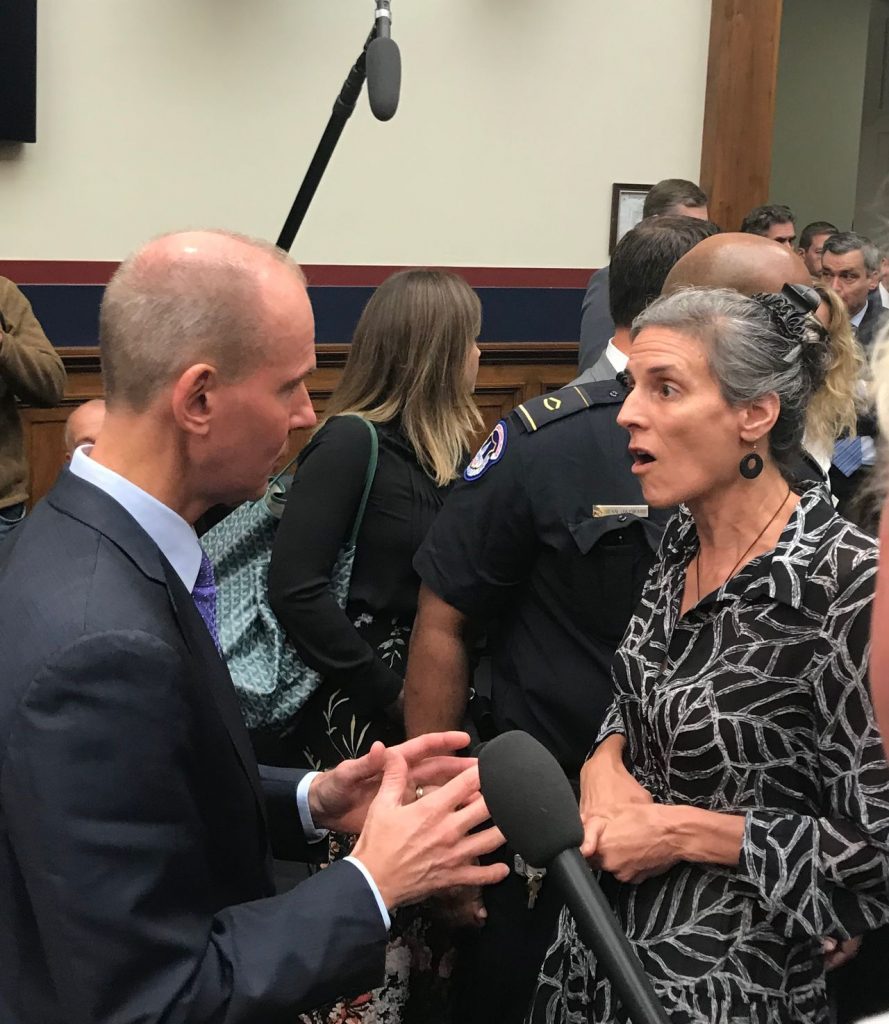

Nadia Milleron and then-Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg. PHOTO: ANDREW TANGEL/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

They haven’t achieved all of their goals. The FAA ungrounded the MAX jets in 2020, against the families’ wishes. In 2022, they unsuccessfully tried to prevent the FAA from certifying delayed versions of the 737 MAX without major cockpit upgrades, though Congress mandated some safety improvements .

Boeing Chief Executive David Calhoun , speaking at the company’s mid-May shareholder meeting, said the plane maker had reshaped its focus on safety after the crashes.

“Our employees remember the lessons learned from those accidents, they apply them in their daily work and they will continue to remember them in the decades to come,” said Calhoun, who took over as Boeing CEO in early 2020.

‘You really want to know why we’re here?’

The Colgan families started mobilizing soon after the 2009 crash, attending a National Transportation Safety Board hearing. They grew alarmed after learning about mistakes and lapses that contributed to the disaster and revelations about the crews’ training, schedules and work habits. At the Capitol, they showed up almost weekly for hearings and honed their message.

The 2010 FAA bill included new safety measures the families had sought. Those included raising experience and training requirements for new airline pilots, updating rules on pilot duty hours and rest time to alleviate fatigue, and mandating creation of a national database of pilot records to improve background checks and screening.

Lawmakers lauded the bill as a triumph for citizen activists and the strongest piece of aviation-safety legislation in decades. A plaque at the FAA’s headquarters recognizes the families for driving safety improvements.

The Colgan families have continued to meet with FAA chiefs, tracking implementation of the safety law’s requirements. Scott Maurer , whose daughter Lorin died in the crash, said he now finds himself explaining the crash and its aftermath to a new generation of lawmakers and staff members who don’t remember it.

At a hearing on a proposed aviation bill last summer, Maurer was seated next to Stumo. A pilot, there to lobby Congress to raise the mandatory retirement age for aviators, leaned over and asked what brought them there.

“Do you really want to know why we’re here?” Maurer asked him. “Both of us lost our daughters.”

Seeking prosecution

The MAX families’ next fight will play out in coming months in a Fort Worth, Texas, courtroom, where prosecutors in 2021 settled a criminal charge against Boeing. That deal allowed the company to avoid prosecution but imposed various requirements, including a three-year probationary period.

With Boeing found in breach of the settlement, the Justice Department could extend the company’s probation, work out a new agreement, take Boeing to trial or seek a plea agreement. At another meeting with DOJ officials on Friday, the families said they wanted the Justice Department to prosecute Boeing and any responsible executives.

“It’s time for the DOJ to show some courage,” said Ike Riffel of Redding, Calif. He lost his two sons, Melvin, 29, and Bennett, 26, in the second MAX accident.

Justice Department officials have told the families they take their input seriously. Leigha Simonton , the top federal prosecutor in Dallas, said in April the department was focused on “doing what’s right by you and your family.”

Write to Andrew Tangel at andrew.tangel@wsj.com , Alison Sider at alison.sider@wsj.com and Katy Stech Ferek at katy.stech@wsj.com