Last year, when he was a college student majoring in computer science and interning at SpaceX, Luke Farritor began working on a problem that captivated many of the world’s brightest young minds, one that could only be solved with machine learning, computer vision and the latest advances in artificial intelligence.

He wanted to read a bunch of 2,000-year-old papyrus scrolls.

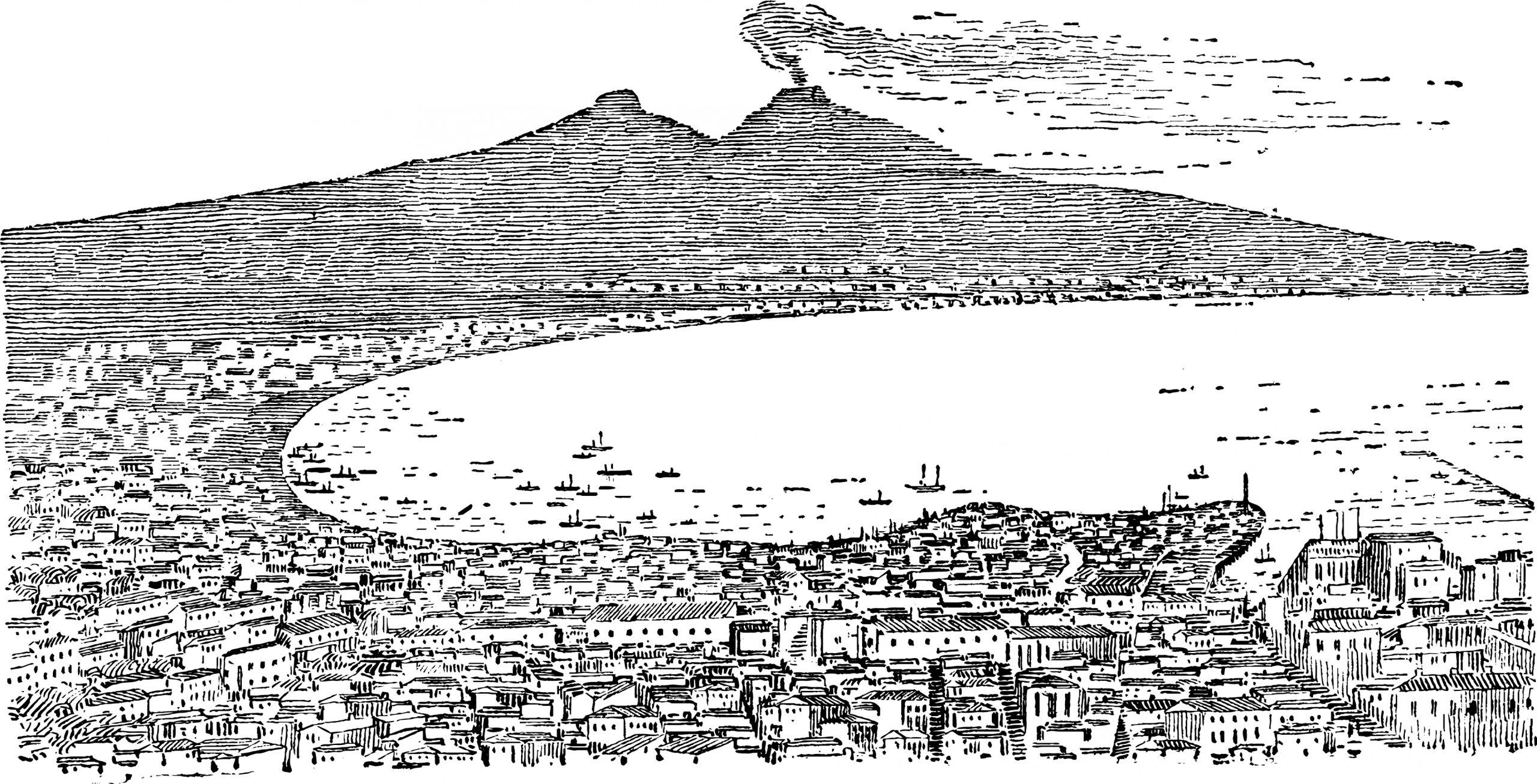

These scrolls known by the seductive name of the Herculaneum papyri have been unreadable since Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 A.D. and they were buried under mud and ashes at a private villa near Pompeii. For centuries, they were lost to history. Even when they were discovered in the 1700s, the carbonized scrolls were too fragile to handle.

Then tech investors, billionaire quants and Silicon Valley luminaries decided to fund the Vesuvius Challenge , a $1 million competition with the crazy goal of using AI to recover a few passages from the Herculaneum papyri. And it actually worked! This week, the Vesuvius Challenge trumpeted a monumental technological breakthrough: The scrolls have finally been opened.

The winning team consisted of three students, including Farritor, 22, who investigated ruins of antiquity from his University of Nebraska dorm room. They didn’t know each other before the Vesuvius Challenge. They still haven’t met in person. But they built on each other’s work and did something together they couldn’t have done alone—something that many thought couldn’t be done at all.

And by looking so far into the past, they’re offering a peek into the future.

“I think this promises a very exciting future where seemingly impossible ideas will become possible,” said another member of the winning team, Youssef Nader , a 27-year-old machine-learning Ph.D. student at Freie University in Berlin.

I mentioned that to Richard Janko , a professor of classical studies at the University of Michigan, who’s been dreaming of reading these scrolls since before the Vesuvius Challenge winners were born. He told me that it didn’t just seem impossible. It really was impossible. “We couldn’t have done this without the tech guys,” Janko said.

Thinking about the Roman Empire

To understand what they did and how they did it, it helps to know the history of the Herculaneum papyri. Or at least the recent history . The quest to unroll them began not with a volcanic eruption two millennia but two decades ago, when University of Kentucky computer scientist Brent Seales devised a method of applying modern technology to crack an old mystery.

The remains of the Herculaneum papyri don’t look like anything left behind by ancient civilizations that might contain the secrets of science, math and philosophy. They look more like something your dog left behind on the rug. The burnt scrolls were in such rough shape that they couldn’t be physically unraveled, which made them a perfect target for Seales’s pioneering research.

The process of virtually unwrapping the Herculaneum papyri involved three steps: scanning, segmentation and searching for ink. It sounds basic, but it’s really bonkers. “It seems like a magic trick,” Seales said. First the scrolls had to be scanned at high resolution by a particle accelerator. Then the sheets had to be identified, separated and digitally flattened. Only then could the machine-learning models find ink. Stephen Parsons , a graduate student in Seales’s lab, published a dissertation last year showing this was theoretically possible. But it was unclear how long it would take to convert theory into reality until Seales received an email from Nat Friedman .

“I ignored it,” he told me, “because I didn’t know who he is.”

Friedman is a tech investor, entrepreneur and the former chief executive of GitHub. In the early days of the pandemic, something odd happened to him: He fell down a rabbit hole into ancient Rome. When he learned about the existence of the Herculaneum scrolls, he became obsessed. When he learned about Seales’s effort to read them, he wanted to help. He wasn’t sure how. But once the professor responded to his email, Friedman pitched him on an unconventional idea: a contest.

One of the many benefits of contests is that they are magnets for talent—especially young talent like Farritor. A brilliant college student with interests in both computer science and archaeology, he was exactly the sort of person with the skills to help. But nobody would have ever asked him.

“This kind of approach to research is grossly underrated,” Farritor said. “I think there should be tons of prizes like this for so many different fields.”

Farritor was an intern at SpaceX last year, listening to Friedman on a podcast while driving to the company’s Starbase facility in Boca Chica, Texas, when he heard about the Vesuvius Challenge. It wasn’t just one thing about the contest that he found alluring. It was everything: the money, the historical significance, the chance to impress his heroes, the idea of bringing tech to new (and old) fields and the sheer adventure of it all. “I also just enjoy working on projects,” Farritor told me. “I can scroll through TikTok, or I can work on this.”

Nader, who is from Egypt, was similarly compelled when he read about the contest on Kaggle , which hosts data-science competitions, though for slightly different reasons. “The word papyrus struck a chord for me as an Egyptian,” he told me. Soon, he was focusing more on the Vesuvius Challenge than his Ph.D. work. “It was like my secret double life,” he said. Before long, he was only thinking about the Roman Empire.

Many of the 3,000-plus tech nerds in the Vesuvius Challenge were students like Farritor, Nader and Julian Schilliger , the third member of the winning team, a 28-year-old robotics graduate student at ETH Zurich in Switzerland. Young people are usually the ones with the time, creativity, raw ambition and curiosity to experiment with new technology. And today’s young people are the ones who will show us how to be smarter about AI.

“In the sciences, it’s the youngest people who are the smartest,” Janko told me. “In the humanities, it’s the oldest.”

Start making sense

The mission to bring ancient Rome back to life began on the Ides of March last year.

The contest was started by Seales, Friedman and his investing partner Daniel Gross , and they crowdsourced the funds to dangle a tantalizing grand prize: $700,000 for the first team to recover four legible passages of 140 characters each by the end of 2023. They knew the Vesuvius Challenge would attract a legion of AI geeks. What they didn’t know was how much progress money could buy.

When he thought about how to structure the contest, Friedman made a crucial discovery of his own: He believed it would be essential to blend competition with cooperation. That’s why the Vesuvius Challenge offered another $300,000 in prizes that rewarded milestones along the way—an incentive for participants to share their progress and code. “If it was just a competition, you’d have teams or individuals work on it and make a little progress, but then give up because it’s way too much work to do for a small chance of success,” Friedman said. He wanted to make that small chance of success much bigger.

For example, when one contestant with a Ph.D. in theoretical astrophysics looked at the scans for a really, really long time, a technique he called “persistent direct visual inspection,” he managed to detect traces of crackled ink hidden in the scrolls. It was a momentous finding that merited a $10,000 progress prize—and Farritor’s attention.

When he read about the discovery of “crackle pattern” in the shape of Greek letters, Farritor trained his machine-learning model on those characters to look for more of them, since it would take computer vision to recognize the ink strokes a human eye could never see. One contribution had inspired another. This was exactly how the Vesuvius Challenge was supposed to work.

Last summer, Farritor moved back to Nebraska, where he lived with five computers in his dorm room, and his AI model spotted a string of 10 letters that spelled porphyras —purple.

This made Farritor the first person in two millennia to read a word in the unopened Herculaneum papyri. It also made him $40,000.

He used some of the money to splurge on a gift for his brother: a vintage poster for the Talking Heads concert movie “Stop Making Sense.” With his share of the $700,000 grand prize, he says he’d like to take his mother to Paris. He’s also thinking about building an autonomous boat to circumnavigate the globe.

The future of the past

Meanwhile, halfway around the world, Nader was plugging away at his own AI models , which earned him a $10,000 progress prize. He invested in a new computer and the access to cloud-computing power he would need to win the grand prize.

By then, there was an active Vesuvius Challenge community on Discord. Now that the seemingly impossible was becoming probable, Farritor and Nader made the strategic decision to join forces. Instead of competing against each other, they would collaborate with each other. In the days before the Dec. 31 deadline, they also teamed up with Schilliger, whose impressive work extracting sheets from the scrolls fed their models with more data. Their entry stood out among the 18 submissions that the Vesuvius Challenge organizers sent Janko and other papyrologists to review—and reveal what people had been waiting thousands of years to see.

So what do the scrolls actually say?

Well, as it turns out, they’re sort of amazing. Likely written by the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus, they discuss topics we’re still talking about today: music, food, pleasure. Basically, how to lead a happy life.

“It’s just incredible to have hit upon something that we can understand and has some universality to it,” Friedman told me. “You can almost see someone writing this on Substack right now.”

Everyone involved with the Vesuvius Challenge is already thinking about what they might do next and how they can apply the lessons of this contest to other seemingly impossible tasks.

But knowing a little bit about the papyri also made them want to know a lot more. The first year of the Vesuvius Challenge unearthed 5% of one scroll. There’s another six-figure prize attached to this year’s goal: recovering 90% of the four scrolls that have been scanned. And they hope that’s just the start. Classics scholars also believe there is a bigger library of hidden treasures waiting to be excavated from Herculaneum that could keep them busy for the next 2,000 years.

Farritor plans to keep working on the scrolls, too. But he might not have as much time: He just dropped out of school to work for Friedman.

His first day on the job was Monday—the day he won the Vesuvius Challenge.

Write to Ben Cohen at ben.cohen@wsj.com