In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the U.S. and the global economy experienced a “China shock,” a boom in imports of cheap Chinese-made goods that helped keep inflation low but at the cost of local manufacturing jobs.

A sequel might be in the making as Beijing doubles down on exports to revive the country’s growth. Its factories are churning out more cars, machinery and consumer electronics than its domestic economy can absorb. Propped up by cheap, state-directed loans, Chinese companies are glutting foreign markets with products they can’t sell at home.

Some economists see this China shock pushing inflation down even more than the first. China’s economy is now slowing , whereas, in the previous era, it was booming. As a result, the disinflationary effect of cheap Chinese-manufactured goods won’t be offset by Chinese demand for iron ore, coal and other commodities.

China is also a much larger economy than it was, accounting for more of the world’s manufacturing. It had 31% of global manufacturing output in 2022, and 14% of all goods exports, according to World Bank data. Two decades earlier China’s share of manufacturing was less than 10% and of exports less than 5%.

Everyone is investing in manufacturing

In the early 2000s, overproduction mainly came from China, while factories elsewhere shut down. Now, the U.S. and other countries are investing heavily in and protecting their own industries as geopolitical tensions rise. Chinese firms such as the battery maker Contemporary Amperex Technology are building plants overseas to soothe opposition to imports, though they already produce much of what the world needs at home.

The result could be a world swimming in manufactured goods, and short of the spending power to buy them—a classic recipe for falling prices.

“The balance of China’s impact on global prices is tilting even more clearly in a disinflationary direction,” said Thomas Gatley, China strategist at Gavekal Dragonomics.

There are some countervailing forces. The U.S., Europe and Japan don’t want a rerun of the early 2000s, when cheap Chinese goods put many of their factories out of business. So they have extended billions of dollars in support to industries deemed strategic, and imposed or threatened to impose tariffs on Chinese imports. Aging populations and persistent labor shortages in the developed world could further offset some disinflationary pressure China exerts this time.

“It won’t be the same China shock,” said David Autor , a professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and one of the authors of a 2016 paper that described the original China shock.

A different sort of China shock

Even so, “the concerns are more fundamental” now, Autor said, because China is competing with advanced economies in cars, computer chips and complex machinery—higher-value industries that are viewed as more central to technological leadership.

The first China shock came after a series of liberalizing reforms in China in the 1990s and its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001. For U.S. consumers, this brought considerable benefits. One 2019 paper found that consumer prices in the U.S. for goods fell 2% for every extra percentage point of market share grabbed by Chinese imports, with the biggest benefits felt by people on low and middle incomes.

But the China shock also piled pressure on domestic manufacturers. In 2016, Autor and other economists estimated that the U.S. lost more than two million jobs between 1999 and 2011 as a result of Chinese imports, as makers of furniture, toys and clothes buckled under the competition and workers in hollowed-out communities struggled to find new roles.

A sequel of sorts appears to be under way.

China’s economy expanded 5.2% last year, a subdued rate by its standards, and is expected to slow further as a drawn-out real-estate crunch crushes investment and consumers rein in spending. Capital Economics, a consulting firm, thinks annual growth will slow to around 2% by 2030. Beijing is seeking to engineer an economic turnaround by plowing money into factories, especially for semiconductors, aerospace, cars and renewable-energy equipment, and selling the resulting surplus abroad.

Deflation in China

But weak demand and overcapacity means Chinese producer prices have been falling for 16 months, led by consumer and durable goods, food products, metals and electrical machinery.

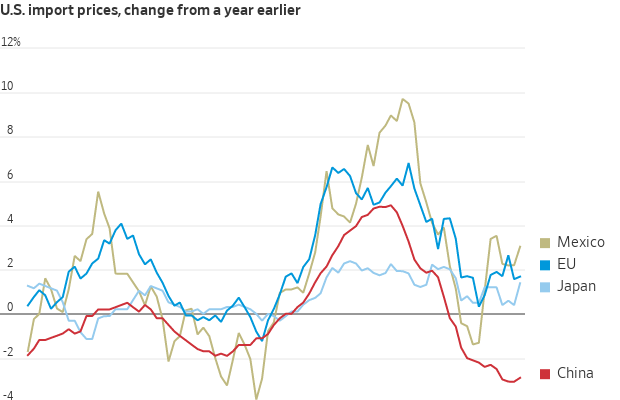

That disinflationary impulse is showing up around the world. The price of U.S. imports from China fell 2.9% in January from a year earlier, while the price of imports from the European Union, Japan and Mexico all rose.

Unlike in the early 2000s, however, the Western world now sees China as its chief economic rival and geopolitical adversary. The EU is considering whether Chinese-made electric vehicles are unfairly subsidized and should be subject to tariffs or other import restrictions. Former President Donald Trump , who is seeking the Republican nomination for November’s presidential election, has floated the idea of hitting imports from China with tariffs of 60% or higher.

Such protectionism might shift some of the deflationary impact to other parts of the world, as Chinese exporters look for new markets in poorer countries. Those economies could see their own fledgling industries shrivel in the teeth of Chinese competition, much as the U.S. did in an earlier era. Unlike Japan or South Korea, which abandoned low-cost manufacturing as they progressed to higher-value exports, China has maintained a commanding position in low-cost sectors even as it pushes into products typically dominated by advanced economies. China represents “a unique mercantilist challenge,” said Rory Green , chief China economist at GlobalData–TS Lombard.

Write to Jason Douglas at jason.douglas@wsj.com