A $16 bacon cheeseburger may not be enough to save your neighborhood bar and grill.

Independent restaurants are on financial life support, owners say, squeezed between escalating payroll costs and diners’ dwindling tolerance for ever-higher checks. Wages for waitstaff, table bussers and line cooks will grow more expensive for many eateries this year, with 22 states in January raising the minimum wage for hourly workers.

The industry’s economic strains can be seen on the appetizer plate at Chef Zorba’s Restaurant in Denver. Owner Karen LuKanic recently swapped Greek giant beans for homemade stuffed grape leaves to save money, and switched to cheaper shoestring potatoes from thick-cut fries. Denver has increased its minimum wage annually since 2020, most recently in January to $18.29 an hour, while Colorado has expanded paid sick leave and other employee benefit requirements.

“We are just keeping our head above water,” said LuKanic, who estimated about half her restaurant’s sales now go to payroll and other employee-related costs.

Chef Zorba’s charges $15.75 for a bacon cheeseburger, $5 more than in 2018. Even at those prices the 78-seat restaurant can’t turn a profit. LuKanic said she would consider closing if her Small Business Administration loan wasn’t guaranteed by her house.

American restaurants emerged from the Covid-19 pandemic to find their traditional economics no longer work. After struggling to stay afloat through lockdowns , restaurant operators endured surging food costs and supply chain shortages. Restaurateurs raised menu prices. In January, prices for food eaten away from home were up 30% compared with the same month in 2019, Labor Department data showed.

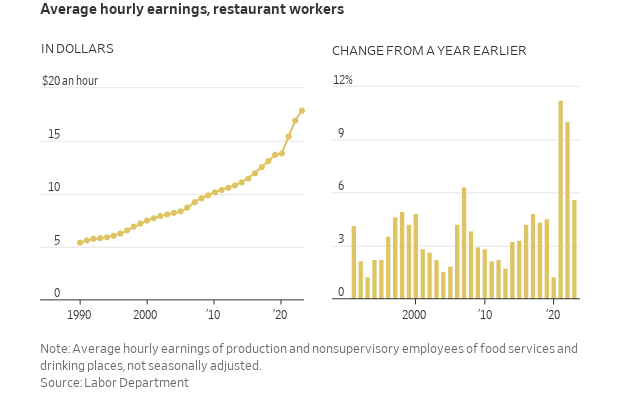

Restaurants’ food bills have stopped their pandemic-era surge. But payroll costs are still climbing.

Tracy Anne Hickman, a server at Chef Zorba’s. PHOTO: RACHEL WOOLF FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

In January, 59% of small-business owners reported higher labor costs were their biggest source of inflation, according to a survey of more than 425 entrepreneurs conducted for The Wall Street Journal by Vistage Worldwide, a business-coaching and peer-advisory firm.

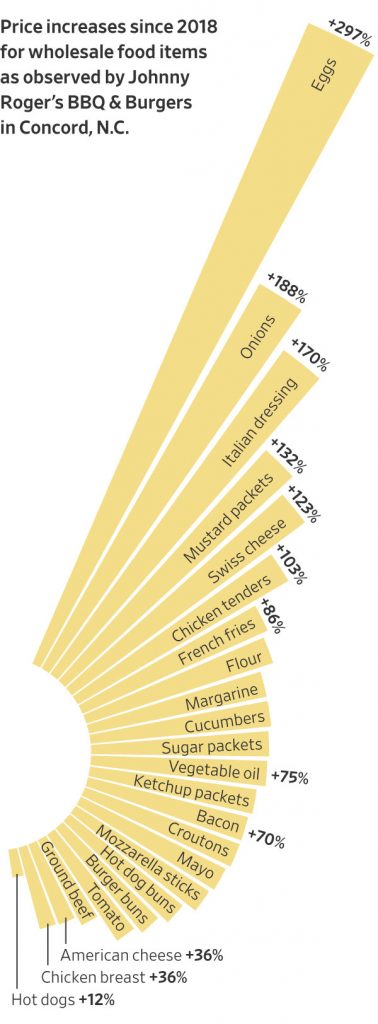

Customers’ postpandemic habits add to challenges. At Johnny Roger’s BBQ & Burgers in Concord, N.C., dinner traffic can be uneven, which means sometimes paying employees who may be idle. Owner and chef Barrett Dabbs tried cutting one front-of-the-house position last year, but ended up bringing it back: “That’s the place where I don’t want to make cuts to save money, something that is directly customer facing.”

Takeout orders account for about 80% of Johnny Roger’s dinner business, up from 20% prepandemic. Dabbs figures it costs him $1 per customer every time someone places a to-go order, because of the extra expense of packaging. To offset costs, he’s raised prices and now asks customers if they want utensils and condiments instead of automatically putting them in the bag.

A Johnny Roger’s bacon cheeseburger now costs $12.50, up from $8.50 when the restaurant opened in 2018. Dabbs hopes to hold the line there. “Customers aren’t going to come visit you if you are charging $14, $15 or $16 for a burger.”

He offers a daily lunch special, priced at $8 plus $1 for a beverage, as a loss leader.

Barrett Dabbs, owner and chef at Johnny Roger’s BBQ & Burgers in Concord, N.C. PHOTO: ANGELA OWENS/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Long-term winners

By some measures, U.S. restaurants are booming. The National Restaurant Association, an industry trade group, forecasts U.S. food-service sales will hit a record $1.1 trillion this year, up 5% from 2023 levels. Employment in restaurants and bars, which fell around 2.4 million jobs at the end of 2020 after the pandemic struck the U.S., have returned to precrisis levels, Labor Department figures show.

McDonald ’s, Chipotle and other takeaway-oriented chains have emerged as long-term winners, while many sit-down establishments struggle. Such full-service dining operations haven’t regained all the workers they had before the pandemic, Labor Department data show, while fast-food restaurants are again fully staffed. Sales for fast-food and other limited-service restaurants grew by more than a third from 2019 to 2023, around twice the rate as sit-down restaurants, according to National Restaurant Association estimates.

The surge in restaurant and bar worker wages since 2021 followed years in which their hourly earnings ticked up by an easier to manage 2% to 4% annually.

For independent restaurants that make food from scratch, higher labor costs are particularly painful.

Evan Kelamis, owner of breakfast and lunch spot Savoy in Tulsa, said his labor costs increased by more than 16% in 2023 alone—though the minimum wage in Tulsa has stayed at $7.25 per hour—because he has to pay more to attract and retain workers.

“There’s tremendous competition with the gig economy,” said Kelamis, a fourth-generation restaurateur. Potential employees can also work for Amazon , Uber or Instacart, he said.

Kelamis expects to raise prices again this year to help pay for meals Savoy workers largely make with their own hands , including items such as shareable half-pound cinnamon rolls. With higher labor costs, his traditional method of pricing menu items——food costs equal roughly 28% of what the customer pays——no longer works. He hasn’t yet figured out what will.

Carving up chicken tenders

At Johnny Roger’s BBQ & Burgers, owner Dabbs is scouring every cost. He recently yanked the television from his restaurant, eliminating an $80 a month cable bill. He found a cheaper source for dishwashing chemicals. Since that supplier delivers monthly instead of weekly, Dabbs for a while stored the extra inventory in his garage until he shifted to a storage space.

He shaved $50 off the $90 monthly storage bill by catering co-marketing events and providing free meals for the storage space’s employees.

“The profit percentages are so low,” said Dabbs, who owns Johnny Roger’s with his wife, Sarah. “For that $50, I’d have to do $600 in sales.”

Owner Sarah Dabbs at Johnny Roger’s BBQ & Burgers in Concord, N.C. The restaurant has been scouring costs. PHOTO: ANGELA OWENS/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Dabbs, who spent years as a food and beverage director for locally owned businesses before opening Johnny Roger’s, now buys jumbo chicken tenders and splits them in-house because the per-pound price of precut tenders has more than doubled. He swapped Heinz ketchup packets for a less-expensive brand. The restaurant, known for its family-recipe barbecue rub and homemade sauces, added a food truck last year, generating more sales with little extra overhead.

For years, desserts such as the “Breakup Sundae,” laden with vanilla ice cream, candy pieces, caramel, chocolate and whipped cream, drew families to the restaurant’s patio on warm evenings. Dabbs put the soft-serve ice-cream machine in storage during the pandemic, then kept it there because it required too much labor to maintain. The restaurant now offers banana pudding, chocolate mud pie pudding and brownies, items that can be prepared in bulk once a day. He pulled homemade onion rings, another favorite, off the menu last year, allowing him to trim kitchen staffing.

Johnny Roger’s labor costs are up about 25% since 2019, Dabbs said, but workers still struggle. “Our employees are right on the poverty level,” he said.

Dabbs runs a holiday coat drive at his two restaurants; some of the coats he collects go to children of employees.

Paycheck to paycheck

Alex Wagner, the restaurant’s operations manager, now earns $17.35 an hour, up from $9.25 when he started at the restaurant six years ago.

Yet expenses have gone up more than pay, said Wagner, 33. “I still live paycheck to paycheck.” Wagner said he would like to buy a car and repair his credit, but can’t because it is difficult to save on his salary.

Dabbs cosigned the lease for the house Wagner shares with his wife, two sons and a roommate. “I am the operations manager. I still need help,” Wagner said.

Alex Wagner is the operations manager at Johnny Roger’s BBQ & Burgers in Concord. PHOTO: ANGELA OWENS/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

As a percentage of sales, restaurants rely on labor more than other retail sectors, making the rise in wages particularly draining on profits, according to industry economists. It takes 12 employees to generate every $1 million in restaurant sales versus roughly three employees at grocery, general merchandise and clothing stores, according to analysis by the National Restaurant Association.

Independent restaurants are less able to spread out administrative costs and command volume discounts. Labor costs have been rising faster and longer at independent restaurants than in the economy as a whole, with full-service restaurants seeing the biggest increases over the last year, according to an analysis by Gusto, a small-business payroll and benefits provider.

Ed Doherty, a franchisee for Applebee’s and Panera Bread who also runs a handful of pubs and wine bars, said he had to re-engineer the menus of his independent establishments to reduce costs in the last year. His chain restaurants, in comparison, had healthy profit margins.

“That’s the advantage of being with Applebee’s and Panera,” he said. “You are able to negotiate prices better than an independent can get.”

About 4,590 more independent restaurants closed than opened last year through November, according to food-industry market-research firm Datassential.

Denver doldrums

When LuKanic first bought Chef Zorba’s from its second-generation Greek owners in 2018, she measured her business against 17 other Denver-area diners. Only eight remain, she said.

The restaurant has operated in a residential section since 1979, where regulars order gyro sandwiches, chicken and rice soup and homemade baklava. With Chef Zorba’s prices up 8% from 2019 levels, some now grumble when they see their checks.

LuKanic knows how they feel. The restaurant’s real-estate taxes have increased 60% since 2019, and energy costs 30%. Theft has added costs: Thieves have carted off Chef Zorba’s propane tanks, outdoor heaters, a $600 storage shed and racks the restaurant had chained up outside. Even rubber floor mats have disappeared while drying behind the restaurant.

In addition to minimum-wage increases, LuKanic now spends thousands of dollars a year for paid sick leave and other employee benefits. She said she’s increased salaries of her managers to around $65,000 a year to remain in line with her hourly workers’ additional pay.

Some of Chef’s Zorba’s 37 workers still feel pinched.

Natasha LaPlante, a 41-year-old server at Chef Zorba’s, said she appreciates her current pay of $18.29 an hour plus tips from a restaurant-wide pool after making $6 an hour when she started waiting tables in Oklahoma decades ago. But LaPlante and her wife are struggling to pay off debts. She said that if her wife lost her job, the family, which includes her wife’s two children, wouldn’t be able to live off her salary alone.

“It’s not like we go out shopping a lot,” said LaPlante.

Lifting prices further would help LuKanic get closer to breaking even, but she worries about scaring away customers used to the restaurant’s average check of $17.25.

LuKanic’s original business loan attached a lien to her house. In 2022, she tapped a federal program for small businesses still trying to recover from the pandemic, which eliminated the lien, but added a personal guarantee for her debt. LuKanic’s house and all her assets now back the restaurant’s financing, and she has little in the way of retirement savings.

“I could go belly up,” said LuKanic, who has a 16-year-old daughter. “I’ve worked my whole life to get where I am.”

Write to Heather Haddon at heather.haddon@wsj.com and Ruth Simon at Ruth.Simon@wsj.com