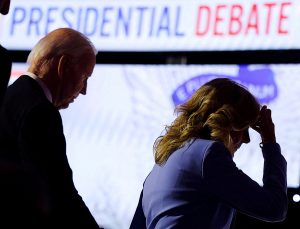

Last week’s presidential debate put the age issue front and center in the U.S. campaign. But there is a different age issue playing out across many Western democracies: a growing bloc of older voters demanding that their needs be met.

Older voters loom large in elections this year in the U.S., U.K. and France. Not only do they turn out to vote more reliably than the young, but they also account for a growing share of the electorate.

As a result, leading political parties in many countries are pledging to protect retirees’ income and health coverage, at a time when growing numbers of retirees will strain government finances. Older voters often are more concerned than younger ones about crime and immigration, and less likely to support environmental initiatives.

In the run-up to Britain’s election on Thursday , every major party backed the country’s “triple lock” guarantee for retirees, which ensures that their state pensions—the British equivalent of Social Security payments—will outpace inflation over the long term. Last year, such pensions rose 10.1%, while the median wage for workers ages 19 to 49 rose by 5.7%. This year, pensioners are set to get another 8.1% bump.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak , trailing in the polls, is promising retirees a tax break, too. For young people, he has proposed a mandatory national service for 18-year-olds—either a year in the military or volunteer work. That plan is deeply unpopular with the young but plays well with those over 55.

British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak visits the Morrisons supermarket as part of a Conservative general election campaign event, in Carterton, Britain July 2, 2024. REUTERS/Phil Noble/Pool

In the current U.S. election cycle, voters appear more concerned about the age of the candidates than whether their policies favor the old. President Biden, who stumbled badly in last week’s debate, is 81, and presumed Republican candidate Donald Trump is 78. As for Congress, the median age of senators at the beginning of this Congress was 65.3, a point at which people are eligible for Medicare, according to Pew Research Center.

“When you’re watching a debate and you see that both of the candidates that are for the primary parties in our country are not going to be here to see the effects of climate change come out, of course that’s not going to be the priority for them,” said Daphne Gould, a 27-year-old flight attendant in Atlanta who said she supports Democrats because of that issue.

Old people have long punched above their weight politically because they vote proportionally more than the young. In the 2022 U.S. midterm election, about two-thirds of citizens 65 and over voted, more than double the turnout rate for people 18 to 29, according to a Brookings Institution analysis of census data.

Demographic change and increases in longevity mean older voters are going to make up an ever larger share of the electorate in many nations. The Netherlands, Norway and Croatia are just some of the European countries where there are now political parties whose main goal is to champion the interests of retirees.

In Britain, in the early 1980s, there were nearly twice as many registered voters under 40 as over 60. Now, the over-60s have almost caught up. But given that they vote more reliably, there are now 1.3 ballots cast by the over-60s for every ballot by under-40s, according to Zack Grant, a researcher at the Nuffield Politics Research Centre at Oxford University who analyzed British election data.

The ballot-box power of the over-60s surpassed that of the under-40s a few years before the triple-lock guarantee was introduced in 2010. By 2028, total spending on state pensions is projected to outstrip spending on defense, education and policing combined, according to UKOnward, a London think tank.

“Our country is tilted to favor the old over the young,” said David Willetts, a former cabinet minister who was part of the Conservative government that implemented the triple lock, a policy he opposed. “Older people…have the money and the power.”

Older voters alone can’t decide elections. Sunak’s party is expected to lose despite overwhelming support from older voters. The Labour Party, widely expected to win the election, wants to lower the voting age to 16, partly to offset the growing clout of older voters. Germany recently lowered its voting age to 16.

Going against the interests of older voters can be politically costly. In France, a move last year by President Emmanuel Macron to raise the country’s retirement age by two years , to 64, sparked months of protests by old and young people alike. Lawmakers refused to pass the bill, forcing Macron to use constitutional powers to make the change without a vote.

Macron’s popularity took a hit , and his party came in third place in Sunday’s first round of voting for parliamentary elections. The first two place finishers, the far-right National Rally and a coalition of leftist parties called the New Popular Front, both opposed the pension changes. The New Popular Front wants to lower the retirement age to 60.

Older voters sometimes favor policies that aren’t in young people’s interests. In 2016, British voters under 35 voted by almost 2-to-1 to remain in the European Union , while voters over 55 strongly favored leaving. Now, the U.K. economy is 5% smaller than it would have been if Brexit hadn’t passed, Goldman Sachs estimates.

“It’s a given that if you’re young, you have less influence,” said Samuel Thomson, a 34-year-old video producer in London. Even young politicians such as Sunak, who is 44, seem to focus far more on older voters, Thomson said.

People gather to protest against the French far-right Rassemblement National (National Rally – RN) party, at Place de la Republique, following results in the first round of the early 2024 legislative elections, in Paris, France, July 3, 2024. REUTERS/Yara Nardi

Pension priority

As baby boomers retire, their pensions and healthcare are accounting for a larger percentage of government spending. Over the past 15 years in Britain, government healthcare spending rose to the equivalent of 7% of gross domestic product, from 6%, while education spending slipped to 4%, from 6%.

In the U.S., the cost of Social Security and Medicare is projected to rise to the equivalent of 10.2% of economic output in a decade, up from 8.3% today, according to the Congressional Budget Office . By 2054, according to CBO, spending on Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid for people 65 and older is projected to account for more than half of the federal government’s noninterest spending. At that point, 25% of the U.S. population will be receiving Social Security benefits, up from 20% today.

“Younger voters who are going to be stuck with the bill aren’t really paying attention to it,” said Brian Riedl , a former Republican Senate aide now at the conservative Manhattan Institute. “So older voters are going to the polls and essentially robbing younger voters.”

Social Security’s costs already exceed its revenues, and in about 10 years, politically toxic automatic benefit cuts will kick in unless Congress acts to fill the gap with options such as higher taxes, transfers from the general fund or borrowing.

A decade ago, Republicans regularly offered plans that would curb Social Security and Medicare benefits for future retirees, which they said would make the programs smaller but more sustainable.

In his successful 2016 campaign, Trump promised not to reduce benefits—co-opting a traditional Democratic stance—and he is sticking to that position in the current campaign. During Trump’s first term, Republican House Speaker Paul Ryan ’s plans for reducing projected Medicare spending went nowhere.

In Germany, the government unveiled a plan in May to preserve until at least 2039 the current formula for determining state pensions for retirees, despite its rising cost. Germany’s government spends more than 100 billion euros ($107.5 billion) a year to prop up the pension system, almost a quarter of all government spending and nearly twice the annual budget for defense.

The average age of registered party members of the ruling Social Democrats in Germany is 60, and 61 for the opposition Conservatives.

“When we connect with people at folk fests and events we organize, many of them are already pensioners,” said Oliver Grundmann, a Conservative lawmaker. “It’s not easy to talk to them about the future. They care about their pensions, about hospitals, about nursing homes, not necessarily about solar power and digitization.”

In late 2021, Spain’s socialist government scrapped an unpopular 2013 overhaul of the nation’s generous state pension system, which allows workers to retire with at least 80% of their preretirement income up to certain limits. The estimated annual cost of rolling back that cost-cutting move will reach the equivalent of 3.5% of GDP by 2050, according to the nation’s central bank. To help pay for it, the government hiked payroll taxes on existing companies and workers.

Protect the old

The idea behind the creation of government safety nets such as Social Security was to make sure older people who stopped working didn’t face poverty and could afford healthcare.

Many current retirees face no such prospect, having benefited from soaring real-estate values and generous retirement savings programs. In the U.S., the median net worth of households led by people age 65 to 74 was $410,000 in 2022, according to the Federal Reserve.

More than 1-in-4 British pensioners is a millionaire in pounds, meaning more than $1.3 million. That figure has risen fourfold in the past 10 years, according to the Intergenerational Foundation, a think tank focused on issues of generational fairness.

James Milne, a 72-year-old retiree in London, bought his small house in the Southwark neighborhood for £152,000 in 2000. “It’s probably worth two million now,” he said. Under a 1980s government plan to encourage homeownership, his wife bought at a discount the public housing where she lived, then later sold it at the market rate, turning a large profit and helping to pay for the couple’s trips to Australia, Indonesia and across Europe.

Milne said he spends his days reading Dickens, enjoying the sunshine by the river and spending time with his two sons in their 20s, who still live at home because they can’t afford their own place. “I love being retired,” he said. “I wish I’d done it earlier.”

For the first time, British retirees have more disposable income than working-age people, once you account for housing costs, according to the London think tank Resolution Foundation.

Yet much public policy still aims to protect retirees. Tax and benefits changes since 2010 have left the average U.K. pensioner about £1,000 pounds a year better off, while households with children 14 and under are £780 pounds worse off, according to the Resolution Foundation .

Workers 65 or older no longer have to pay an 8% “national insurance” tax to fund welfare spending, effectively giving them a pay raise even though they often earn more than young people. While in the U.S. many homeowners pay capital-gains taxes when they sell homes that have soared in value, in Britain, it’s the other way around: The buyers, who tend to be younger, pay a tax.

Younger people in Britain are the first generation to have lower rates of homeownership than their parents.

“Owning a home for me is just not on the cards,” said Adam Lamb, 31, an Oxford University graduate who teaches Spanish and French at a public school in south London. Lamb lives in a cramped three-bedroom house in south London with two friends. Nearly half his income gets taken up with rent and utilities. He is still paying off his student debt and has no savings.

Younger millennials such as Lamb, born in the late 1980s, earn on average 8% less at age 30 than members of Generation X, born 10 years prior, at the same age. It will take them at least five more years of working full time to become homeowners than their parent’s generation, and they can expect to retire with £45,000 pounds less in savings, according to the Resolution Foundation.

One reason home prices are so expensive in Britain is a chronic shortage of newly built ones.

Leo-Gibbons Plowright, who worked on the Lewisham city council in London, said roughly nine in 10 housing proposals were turned down. “You get lobbied like crazy, with emails and petitions and people turning up,” he said. “Usually, it’s the existing homeowners, and the people who have time on their hands to do that are retirees.”

Write to David Luhnow at david.luhnow@wsj.com and Richard Rubin at richard.rubin@wsj.com