Most Americans will be setting their clocks forward on Sunday, an annual ritual that allows them to start fighting about daylight-saving time an hour earlier.

The experience—interrupted sleep, tired children—is so distasteful that in recent years there have been growing calls to get rid of the clock change altogether.

President Trump has seized on the cause. “The Republican Party will use its best efforts to eliminate Daylight Saving Time, which has a small but strong constituency, but shouldn’t!” he wrote in a post on Truth Social in December. But in 2019 he tweeted that “Making Daylight Saving Time permanent is O.K. with me!”

Economists have jumped into the debate. Daylight-saving time’s original selling point was to reduce energy use by making sunsets later in the day. New research questions that claim.

Preliminary findings from Yale economist Matthew Kotchen , with Arianna Salazar-Miranda, Erin Mansur and Steve Cicala, suggest that in some places daylight-saving time saves electricity, while in others it uses more, with the overall effect across the U.S. basically a wash. The upshot is that electricity saved by behavior such as leaving lights off until later in the evenings is spent in the darker mornings by doing things like turning on the lights to make sure our socks match.

Separately, traffic-flow data the researchers are analyzing suggest that daylight saving might lead people to drive more—which doesn’t exactly save energy either.

More driving is certainly the case when daylight-saving time starts each March, which is understandable: A lot of outdoor sports practices begin the week after the clocks change, for example. And Kotchen suspects it is also true across daylight-saving time in general: No matter what time the sun rises, most people aren’t going to hit the golf course or grab a meal with friends before they go to work.

FILE – Dave LeMote uses an allen wrench to adjust hands on a stainless steel tower clock at Electric Time Company, Inc. in Medfield, Mass., in this March 7, 2014 file photo. Most Americans will set their clocks 60 minutes forward before heading to bed Saturday night March 7, 2015, but daylight saving time officially starts Sunday at 2 a.m. local time (0700GMT). (AP Photo/Elise Amendola, File)

This isn’t the first time Kotchen has examined daylight-saving time and its effect on the economy. A 2008 paper with economist Laura Grant analyzed detailed consumer electricity-use data in Indiana—and showed that daylight-saving time actually led to greater electricity use .

Daylight time

The idea that shifting our days forward could save energy goes a long way back. In 1784, a century before the establishment of global time zones, Ben Franklin advocated rousing Parisians earlier to reduce the City of Light’s candle usage. The U.S. instituted daylight-saving time in World War I and World War II, also to save energy.

Congress codified the dates for daylight-saving time in the 1960s. It lengthened daylight time starting in 1987, and again starting in 2007, so that it now lasts eight months of the year. For both those extensions, the reason cited was, once again, to save energy.

Many businesses favor daylight time over the alternative, known as standard time. An outdoor cafe might attract customers later in the evening, while a golf course could fit another foursome in before nightfall. In the 2007 extension, the end of daylight-saving time moved from the last Sunday in October to the first Sunday in November, adding an extra hour of light to Halloween evenings. It was a provision that excited candy makers, on the expectation of better Halloween sales.

But for some lawmakers, eight months of daylight time isn’t enough. In an effort led by Sen. Marco Rubio (R., Fla.), now secretary of state, the Senate in 2022 passed the “Sunshine Protection Act.” The bill proposed making daylight-saving time permanent, and it passed by unanimous consent . But it went no further.

Sen. Ed Markey , a Democrat from Massachusetts who co-sponsored the 2022 bill, has been backing daylight time for decades. As a representative, he introduced the legislation behind both the 1987 and 2007 extensions, and now favors permanent daylight-saving time.

“It’s time to lock the clock so we can spring forward into permanent sun and smiles,” Markey said in a statement to The Wall Street Journal.

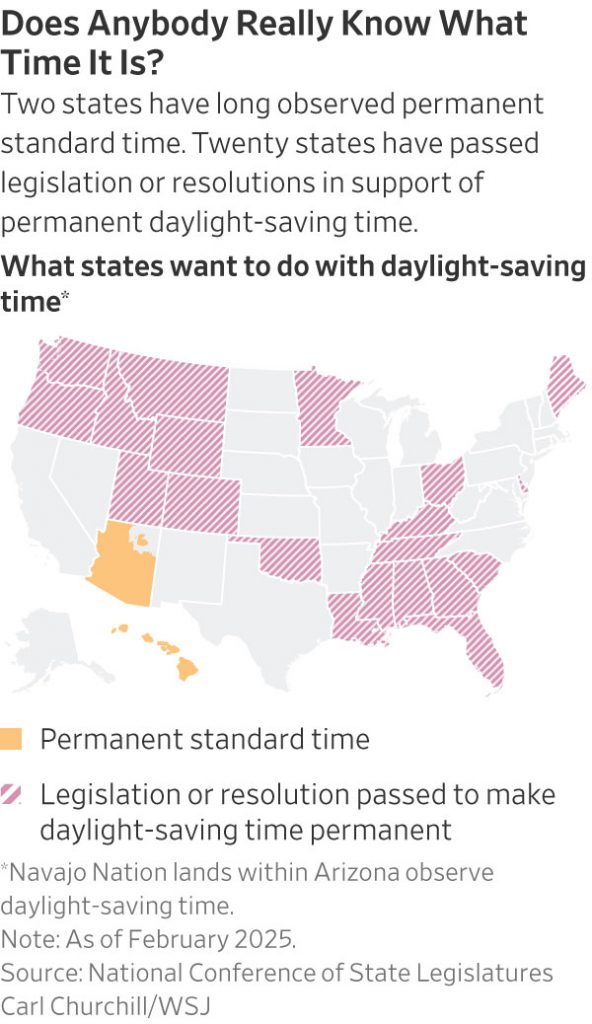

Twenty states have passed legislation or resolutions to move to permanent daylight time, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. But they haven’t actually moved: Federal law doesn’t currently allow states to go to permanent daylight time.

However, the law doesn’t preclude states from staying on permanent standard time. For example, Arizona stays on standard time year-round, excluding the parts of the state that are within the Navajo Nation. The extreme heat in the summers would make the later part of the day much hotter under daylight time.

Standard time

Sleep scientists say that lawmakers who want permanent daylight time are picking the wrong side. Research suggests staying on standard time would be better, for health reasons .

The American Medical Association in 2022 called for permanent standard time. The period after the spring clock change, after all, has been associated with increased health risks, such as shorter sleep, more car accidents and an increase in heart attacks.

What’s more, daylight time puts body clocks and alarm clocks at odds with each other, the organization said.

The body clocks that organize our daily rhythms tend to respond to the sun’s position in the sky, explains sleep scientist Elizabeth Klerman , professor of neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. Our social clocks—the times that are on our watches and phones—are what’s set by society so we can coordinate our schedules.

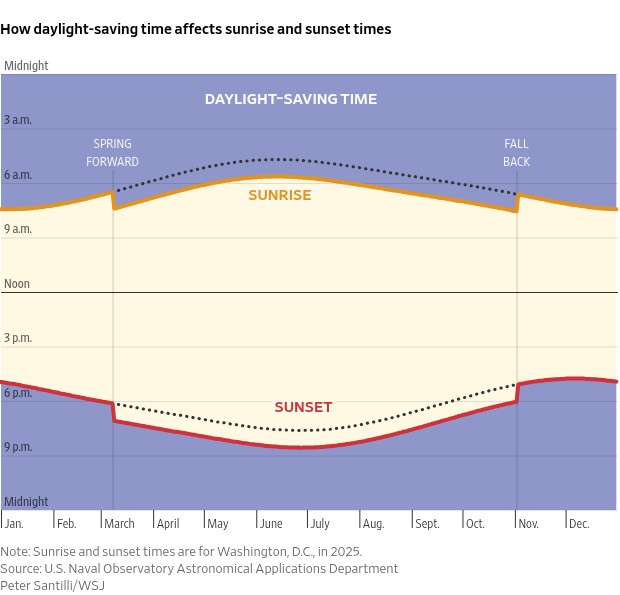

Ideally, our body clocks and social clocks should be closely aligned. Standard time, where daylight hours are earlier in the morning, is the better option, sleep experts say. In the middle of a time zone during standard time, the sun is at its highest point right around noon. During daylight time it’s at its highest around 1 p.m.—throwing the whole day off.

Dark mornings vs. dark evenings

To a degree, whether people are in favor of moving to year-round daylight-saving time could be a function of where they live. Markey, the daylight-time proponent, is from Malden, Mass., on the eastern edge of the Eastern Time Zone. Its latest sunrise occurs in early January, at 7:13 a.m. A move to permanent daylight saving would push that to 8:13 a.m.

Bill Schuette, a Republican in Michigan’s House of Representatives, is from Midland, Mich., in the western portion of the Eastern Time Zone. Its latest sunrise in early January comes at 8:10 a.m. A move to permanent daylight would make that 9:10 a.m. Schuette introduced legislation to put Michigan on permanent standard time last year.

It didn’t progress, and he thinks it is far from the most important thing he has worked on. But nothing he has done before has prompted so many calls to his office, and he learned that it is truly a bipartisan issue—as in, there are both Republicans and Democrats who love the idea of Michigan moving to permanent standard time, and other Republicans and Democrats who really hate it.

“It really has been an interesting civics crash course,” he said.

Kotchen, the Yale economist, isn’t sure the public would support going on permanent daylight-saving time or standard time for long. The U.S. experimented with permanent daylight time starting in January 1974, in response to the 1973 oil shock. People hated it: They struggled to get up, rouse children for school and go to work in dark mornings. Clock changing was reinstated that fall.

The experiment yielded no definitive energy savings—which was one of the main points in the first place.

Year-round standard time might not fly either: The transition to daylight-saving time is harsh—maybe more so since it moved in 2007 to early March from early April—but people might miss the late-summer light.

“I think what we have now is probably like splitting the difference in a way that is the right balance,” said Kotchen.

Trump on Thursday appeared to have lost his enthusiasm for tackling the issue. “A lot of people like it one way,” he said. “A lot of people like it the other way.”

Write to Justin Lahart at Justin.Lahart@wsj.com