JACUMBA HOT SPRINGS, Calif.—About a mile north of the U.S.-Mexico border, a makeshift collection of multi-colored blankets and tarps blooms in the desert. The people waiting there are migrants from around the world , most of whom snuck through a gap where an 18-foot steel wall meets a rocky hill outside this desert town about an hour east of San Diego.

The camp has a name, hand-painted on a plywood sign and lit with a solar-powered light for people arriving at night: Campo de Asilo, or Asylum Camp. Run by an aid group, it’s a destination for migrants planning to turn themselves in to U.S. border agents and request asylum.

That simple request is the main driver of record illegal immigration in much of the Western world. People travel thousands of miles, on foot and across seas, to turn up at the land borders of rich countries to ask for asylum, a form of legal protection for people who face persecution in their home country.

It’s also become a key loophole for economic migrants, who aren’t under threat but want better working opportunities. Quirks in the law and an overwhelmed processing system nearly guarantee entry, at least for a time.

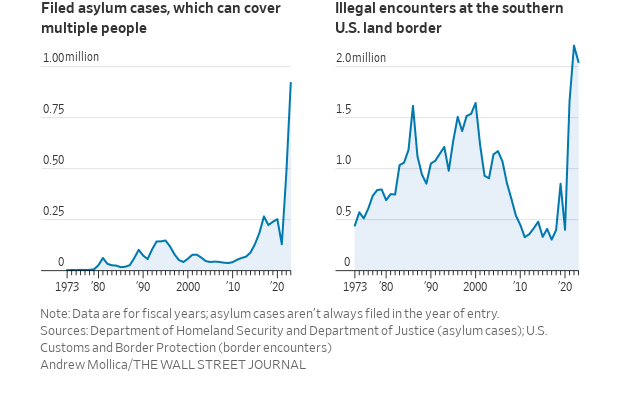

The U.S. received more than 920,000 applications for asylum during its 2023 fiscal year, compared with just 76,000 in 2013. Since a single application can cover multiple members of a family, the figures underestimate the actual numbers of people seeking asylum.

Family groups, who now almost always ask for asylum, make up about half the roughly two million people encountered by authorities who illegally crossed the U.S. frontier with Mexico last year. Another half million came through legal ports of entry, many using a Border Patrol smartphone app that launched in January 2023 to make an appointment to cross and ask for asylum.

Part of the surge is caused by events including the war in Ukraine, the return of the Taliban in Afghanistan, Syria’s civil strife and the brutal rule of authoritarian regimes in Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua. There is greater mobility nowadays, and sophisticated networks of smugglers are willing to move people across borders. And tips for using the asylum law now abound on social media.

The law in the U.S. typically gives migrants who have a reasonable claim of persecution the right to live and work in the country while their cases progress through the courts. So many are now coming that the U.S. lacks the capacity to quickly screen their cases, either at the border or in courts, where a typical asylum case now takes four years .

Even if an application is ultimately rejected, migrants by then have put down roots, often had American children and are rarely deported because of the costs and logistical challenges. They are left in limbo—they lose the right to work legally but aren’t kicked out.

Yet with the road to legal migration increasingly difficult even for migrants with high-tech skills, asylum is for many seen as the most viable way into the U.S. “If it’s not asylum, there are very, very few options,” said Rebecca Press, an immigration lawyer in New York who frequently handles asylum cases.

Kevin Chiluisa, an Ecuadorean who crossed the border in the desert into Arizona in September, said he wasn’t fleeing violence or oppression. He simply wanted a better life than the one he had in a small town in Ecuador’s eastern jungle region. Like many others, he wasn’t asked why he came when he handed himself in to Border Patrol—agents just began treating him as an asylum seeker. He now lives in Chicago with a cousin and gets by working odd jobs while awaiting his first immigration court hearing.

He’s not sure if he’ll be eligible for asylum, or whether he should even turn up to court. “They want to verify what you’re saying is true,” he said of the hearings. “I don’t have that.” If he loses, or decides to give up and stop showing up to immigration court, he is considering simply melting into the underground society of undocumented migrants and making a new life.

Top political issue

The numbers have overwhelmed the courts, Customs and Border Protection and the budgets of cities offering shelter to migrants , putting the issue of immigration at the top of political debates and the coming presidential election.

A Wall Street Journal national poll conducted in late February found that 20% of voters now rank immigration as their top issue , ahead of the economy, which had taken the top spot in December.

Texas has fought to take more control of immigration across its borders. Its aim to arrest and deport immigrants , being contested in federal court, has added even more disarray to U.S. immigration policy.

It’s a global issue. Europe, which has even greater protections for would-be asylees than the U.S., received 1.14 million asylum seekers last year , the highest since 2016, when a wave of migrants sparked by Syria’s civil war overwhelmed European borders. The issue has fed the rise of the far-right in countries across the continent. The U.K. spends the equivalent of $3.9 billion a year putting up asylum seekers in hotels while they wait for their cases to journey through overcrowded courts.

Germany received more than 330,000 asylum applications from people who turned up at its border last year—not including those from Ukraine—a more than 70% rise from 2022. Canada’s asylum applications more than doubled last year to nearly 138,000. Globally, the U.N. registered a record 2.6 million asylum applications in 2022, the latest year of available data and a 30% rise compared with pre-pandemic levels.

Countries are grasping for solutions. Italy recently struck a deal to make asylum seekers wait for their decisions in Albania. The U.K., Denmark, and Germany are all exploring ways to send asylum seekers permanently to third countries, including in Africa.

“The original idea was to provide protection for people who needed it, but what it’s become is a pathway to immigration,” said Alexander Downer, the former foreign minister of Australia, which has taken the hardest line against asylum seekers of any country in the West.

Migrants are checked before boarding a bus to be processed near Jacumba, Calif., in February. PHOTO: ARIANA DREHSLER FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

In 2013, when more than 20,000 people in small boats turned up in Australia—with scores more dying at sea—the country essentially suspended territorial asylum. Australia still accepts refugees, but only those who process their claims abroad and fly in. Small boats now get intercepted at sea, and people seeking asylum are sent to another country paid to house them. Even if they win their case, they are usually not resettled in Australia. Within two years of the policy, boat arrivals dropped to zero.

In the U.S., so many people illegally entering now request asylum that the Border Patrol rarely bothers asking migrants if that’s why they have arrived. They simply direct them to wait in places set up by migrant aid groups, such as Campo de Asilo, until they can be driven to Border Patrol stations to be fingerprinted, given information for their first court appearance and returned to aid groups or dropped off at bus stops.

On a recent morning inside the Asilo camp, about 100 people from countries including Ecuador, Vietnam and Turkey braved an early morning chill waiting for Border Patrol agents to pick them up. Spread out in small groups among the rocky encampment, migrants lined up for snacks and drinks handed out by volunteer aid workers. The Border Patrol arrived within a few hours and directed migrants to walk to a nearby road where a bus was waiting to drive them away from the border.

Nearly everyone at the camp and a similar one nearby said they learned they should ask for asylum from social-media posts by migrants who came before them.

Sardor, a 27-year-old Russian man, said he learned about asylum from posts on Telegram. Sebastian Fernandez, a 19-year-old from Ecuador, said he saw internet posts and news reports explaining that he could “ask for help” at the U.S. border. He hoped to make it to New York, he said, where a brother has been living.

Yacoubou Ismael, a 35-year-old man from Benin, said he hopscotched around the world after seeing other migrants post about entering the U.S. and requesting asylum. In one month he traveled to Greece and then Latin America, before making his way north through Mexico. “It was difficult, but America was always the objective,” said Ismael.

‘Looking backwards’

Republican and Democratic lawmakers agree the asylum system needs overhauling, but have long been unable to pass an immigration reform package . The most recent proposal, which failed in a Senate vote, would have created a rapid asylum decision process and a toughened initial screening.

International law began compelling governments to grant asylum to immigrants who suffered or had a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country in the late 1940s, after many nations had earlier refused to give shelter to Jews fleeing the Holocaust.

In the following decades, the U.S. took in refugees through a series of policies that often targeted a single area, including some 200,000 fleeing Communist countries in the 1950s.

In 1980, the U.S. adopted the Refugee Act, which allowed entry of up to 50,000 refugees a year from all over the world. A refugee is typically someone who has been determined by a court or an expert to qualify for asylum.

Cases were usually processed while people were still overseas. Defectors and dissidents or refugees from places such as Vietnam or Cambodia who had been pre-vetted and granted visas made up the bulk of the numbers.

In an age before mass transit and instant communications, few people pictured masses of asylum seekers turning up at land borders unannounced. Despite its cap on refugee entries, the U.S. still doesn’t regulate the number of people physically crossing the border and asking for asylum—if a person arrives, the law requires that the case be heard.

Within months of the Refugee Act, Cuban dictator Fidel Castro announced that any Cuban wishing to go to the U.S. was free to leave from the port of Mariel. About 125,000 people, including people released by Castro from prisons and mental institutions, took him up on it, forcing the Carter administration to allow them in under separate legal authority called humanitarian parole.

“The paradox is we enacted the Refugee Act looking backwards at the experiences we already had rather than forwards to what might happen, and we suddenly realized, ‘Oh, my gosh, this might not just be small groups of people,’” said Doris Meissner , who was head of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service under the Clinton administration.

Things began to change around 2014. The Border Patrol, accustomed to chasing down single Mexican men who snuck across the border looking for work, suddenly began encountering families from Central America turning themselves in and asking for asylum.

The new wave of asylum seekers slowly caught on, fueled by migrant families telling others back home that they had successfully made it into the U.S. The rise of smartphones made it easier for migrants to spread the word.

Popular social-media accounts in the U.S. and Latin America tout asylum as a simple way to enter the U.S. and offer practical tips. “You have to have a script,” one video says. “You have to tell your story in a chronological order, with dates, with times and with a sequence of how the events that affected you happened. Many people do not prepare and their memory betrays them.”

The growing use of asylum claims overwhelmed the system and made it nearly impossible to address cases on the spot—immigration officials at the border can screen entrants and determine whether they have a “credible fear” of being returned to their own country, rejecting those outright who don’t meet that requirement. Only a few hundred screenings a day out of several thousands of border encounters now take place.

In fiscal 2013, just over 80% of all border encounters ended in repatriation. But as asylum claims grew, that number fell to about 30% in 2019, the most recent year of data available, according to the Department of Homeland Security. The percentage of families repatriated within three years of their initial arrival at the border fell from 44% in 2013 to 6.2% in 2018, the latest year with available data. It is now likely even lower, immigration experts said.

Andrea Holguin, 33, was fed up with life in Venezuela and was having trouble feeding her daughters. In 2019, she left for Ecuador, which wasn’t much better. In August, she set out for the U.S., leaving the two girls with her parents.

She first had to cross the Darien jungle in Panama—a dangerous stretch of wilderness without roads that separates South America from Central and North America. The number of people crossing the territory has risen from 559 in 2010 to 520,000 last year, according to Panamanian government data. Most are headed for the U.S. border.

Holguin then rode by bus to Mexico City and eventually to the border. From there, she tried to use the Border Patrol’s smartphone app, called CBP One, which offers 1,450 appointments a day for would-be asylum seekers to cross the border legally and have a credible fear interview with officials.

But after weeks of waiting, she ran low on money and gave up, so she walked across the border near El Paso, Texas, and surrendered. She was housed along with other migrants in a large, dormitory style tent. Immigration authorities took her name, fingerprints and other biographical information, as well as her photograph.

“When they took my fingerprints, a migration official asked if I was pregnant and if I was allergic to any medicine,” Holguin said. “That’s all they asked me.”

She signed some paperwork and was let go. Within three days, she was heading for the Bronx to join her Venezuelan boyfriend, where she now lives. The two share a small room, paying rent of $800 a month, with one lightbulb attached to the ceiling for illumination. The building is packed with other migrants from Latin America.

On Friday, Holguin took the subway for her first hearing before an immigration judge, Anna Diao, who explained to her and a group of migrants the steps needed to secure asylum. Holguin now has to apply in writing and return for a longer hearing on the merits of her case next March.

“That’s where you have to say, ‘I fled Venezuela,’ and why I’m asking for asylum here,’” Holguin said, dressed in jeans and only a white sweatshirt on a chilly day. “Obviously, as the judge said to us, we have to present proof, what a witness said, the documents that can help with that.”

Holguin waited at a federal building in New York for her hearing on Friday. PHOTO: OSCAR B.CASTILLO/FRACTURES COLLECTIVES FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Holguin said she will describe in her application, and later tell an immigration court, how the father of her daughters in Venezuela had been physically abusive. And she will also talk about how pro-regime supporters in Venezuela threw rocks at her when she had refused state-paid boxes of food, which the government uses to get voters to the polls.

Holguin, though, said she’s worried she can’t come up with the evidence needed to get asylum since old text messages and photographs may be gone and people who know about her situation remain in Venezuela.

If she doesn’t get asylum, Holguin said she would try to find another way to stay. “I’ll appeal to see if I could stay under another migratory status…it wouldn’t be asylum, but some other method.”

Yearslong cases

There are two ways to claim asylum in the U.S.—both of which have been stretched to the breaking point. People already in the U.S., such as tourists or students, or migrants using the CBP One smartphone app, apply for “affirmative” asylum. They go through DHS’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, which says its case officers have the capacity to handle 50,000 asylum cases a year. The numbers far exceed that capacity. The government had 431,000 cases in the fiscal year that ended in September.

People caught crossing the border illegally, such as Holguin, are entered into the immigration court system and usually claim “defensive” asylum, so called because they are using asylum as a defense against being deported. Their cases are sent to one of the Justice Department’s roughly 70 immigration courts, which handle asylum and other types of immigration cases. The system’s 700 or so immigration judges each usually handle a few hundred cases a year.

Last year, some 465,000 migrants filed new defensive asylum claims, part of a broader backlog of 3.4 million immigration cases, of which more than a million are asylum claims.

During the court process, the applicant tries to prove they face persecution in their home countries with whatever evidence they can muster—threatening text messages from a government or gang, for instance, or even newspaper articles.

About one in five people win their cases. Those that lose, though, rarely have to worry about being deported, because of the resources it takes to expel migrants. Immigration agents have to identify where the person lives, know when they will be home and turn up with agents and firepower in case the person or their family resist. Such raids often spark negative publicity and protests. Repatriation—often done via airplane—is expensive. And some countries won’t take people back. Venezuela, for instance, has cut off permission for the U.S. to send back migrants.

DHS says on its website that noncitizens who aren’t repatriated within 12 months of being encountered at the border are “rarely repatriated after that.”

Ibrahima Bah, shown with one of his daughters in Colombia, fled with his family from Guinea, traveled through South and Central America to cross into the U.S. and is now applying for asylum. PHOTO: CARLOS VILLALON FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

As a result of the logjam in the system, asylum seekers that appear to have valid claims of persecution have to wait for their cases alongside those who concede they are economic migrants.

Ibrahima Bah decided to flee Guinea after his in-laws took his daughter Assiatou to undergo genital mutilation. The 7-year-old died during the procedure. He feared the same fate could befall Assiatou’s twin, Hadja, and that their older sister, Fatoumata, would soon be forced to marry against her will.

Bah, his wife and two surviving daughters flew to Brazil before braving bus trips through the Amazon, a slog through the Darien jungle and corrupt police in Mexico. They reached the U.S. in September.

“I want my daughters to be protected,” he said. “To grant them asylum and be protected, and also for them to have a better education and to have a life that they are free to live.”

The family has taken part in one preliminary immigration court hearing, carried out online. Bah doesn’t yet have permission to work, and the family sleeps in one room in his friend’s house. He said he is eager to have his case heard by a judge but has no idea how long it will take.

Write to David Luhnow at david.luhnow@wsj.com , Alicia A. Caldwell at alicia.caldwell@wsj.com and Juan Forero at juan.forero@wsj.com