PORTO ALEGRE, Brazil — In a country with a history of corruption and government inefficiency, Councilman Ramiro Rosário has come up with what he believes is a winning strategy to improve the work of politicians: replace them with computers.

The 37-year-old legislator in Brazil’s southern city of Porto Alegre passed the country’s first law in November that was written entirely by ChatGPT, the artificial-intelligence chatbot developed by the San Francisco startup OpenAI.

The law itself was purposefully boring—a proposal to stop the local water company from charging residents for new water meters when they were stolen from their front yards. It would easily pass, calculated Rosário.

One recent day, donning jeans and sneakers, Rosário described how the city usually runs (or crawls) under Porto Alegre’s 36 councilors, from a warren of cubicles here in a vast modernist building overlooking the Guaíba River.

Under normal circumstances, it would have taken his six-person team several days to draft the bill. There would have been lengthy discussions over the legalese, interjected with dozens of coffee breaks and some heated discussions over the performance of Grêmio, one of the city’s local soccer teams.

His assistant would have had to figure out the inner workings of DMAE, Porto Alegre’s water and sewage authority. (Rosário said hehad asked DMAE for help but they never replied to his message.) DMAE didn’t reply to a reporter’s request for comment about not replying to Rosário’s request.

Then some poor soul would have had to check if the bill was even constitutional, Rósario said—no small feat given that Brazil’s constitution is 64,488 words-long, outdone only by those of India and Nigeria.

Add to that several typically protracted Brazilian working lunches—followed by more coffee—and perhaps one of the country’s many public holidays, which if on a Thursday would have been unofficially extended to Monday.

But, in fact, none of that was necessary. ChatGPT got the job done in 15 seconds.

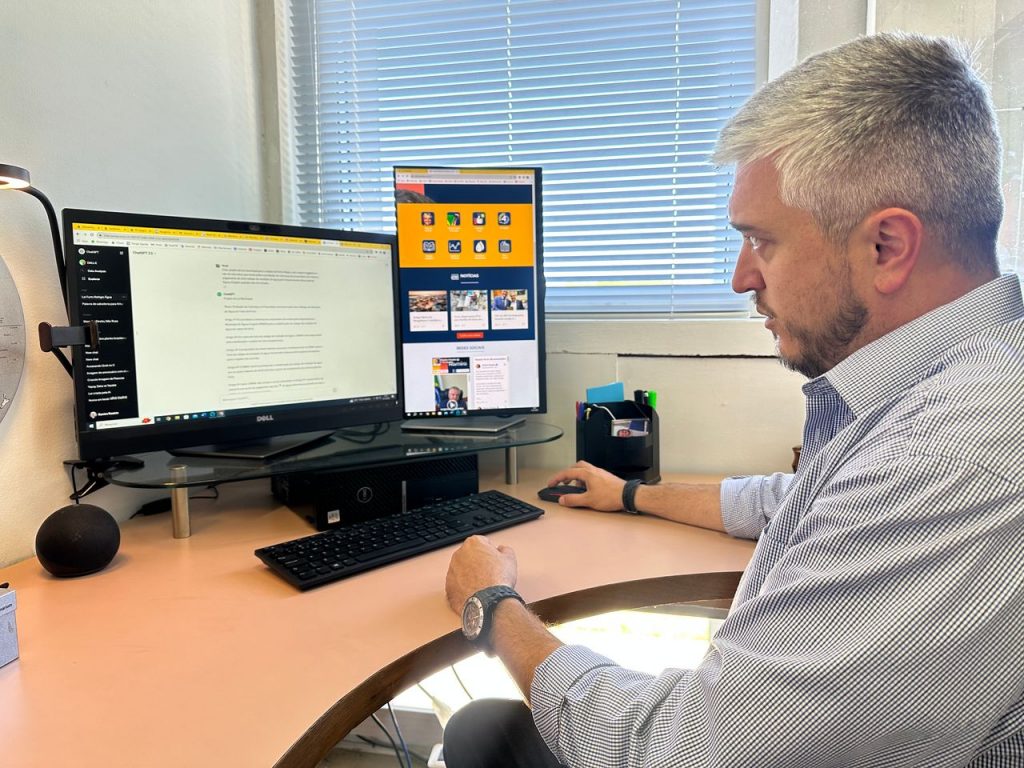

Rosário consults the ChatGPT website in his office. PHOTO: SAMANTHA PEARSON/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Rosário sat down in front of his computer back in June and described the bill he wanted in a sentence. A perfectly-crafted law with eight articles came back, including a clause Rosário had never thought of: if the water authority didn’t replace the stolen meter within 30 days the property owner would be exempt from paying their bill.

“Who knows where she got the 30-day thing from! She went above and beyond!” said Rosário, an AI enthusiast who said he likes to talk to “her” daily. After the release of ChatGPT’s latest vocal version in Brazil, the chatbot has taken on a friendly woman’s voice with a slight country twang—a peculiarity ChatGPT itself suggests may be because the bulk of its input data comes from São Paulo, Brazil’s richest state and agricultural powerhouse.

“There was one day I asked for help in the kitchen. I told her: ‘Listen, all I have in the fridge is a mango, a lime, an apple, and an open bottle of wine,’” Rosário digressed. She came up with a recipe for pasta with a mango sauce and told him to drink the rest of the wine. “It was delicious!”

He also called on her to help settle an argument with his brother-in-law over the Israel-Hamas war. “He was saying stuff that just wasn’t true,” Rosário said. “So we went to ask her and, before we knew it, the three of us were having a conversation.”

Rosário put the drafted legislation up for vote exactly as ChatGPT had written it. It was unanimously approved by the city’s other councilors and signed into law by Porto Alegre’s mayor at the end of November. Chat GPT even whipped up the press release.

Porto Alegre sits on the banks of the vast Guaíba river, some 200 miles from the Uruguayan border. PHOTO: SAMANTHA PEARSON/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

It was only then that Rosário revealed to the rest of councilors that he hadn’t written a word of it. “They would never have signed it if they’d known.”

Other countries have embarked on similar experiments. A judge in Colombia recently used the chatbot to decide whether an autistic child’s insurance should cover his medical treatment, while an Indian judge called on it to help determine whether a murder suspect should be granted bail.

But Rosário said he believes his law was the first in the world to be written entirely by ChatGPT. (As he talked, he picked up his phone and checked with the chatbot for confirmation, glowing with pleasure as she praised him for his efforts on what she called a “fascinating” subject.)

Rosário’s cause was a noble one. Brazil spends more than 13% of its gross domestic product on the salaries and pensions of public servants. He wanted to demonstrate how much more efficient and cost-effective the government could be if it employed AI instead of so many people.

The idea isn’t to replace all politicians and public servants, just some of them, he said with a grin. He cited, for example, the city hall’s public-relations assistants down the hall who write news releases like the one ChatGPT just churned out. “There must be 20 or 30 of them—they probably won’t be needed in the future, well, to be honest, they’re already no longer needed.”

Ramiro Rosário visits the overflowing archive department of Porto Alegre’s city hall. PHOTO: SAMANTHA PEARSON/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Voters were delighted by Rosário’s maneuver. “I’d choose artificial intelligence over the intelligence of politicians any day,” said Adriano Soares, a 21-year-old student in the city. Politicians frequently rank as society’s most hated group in Brazil. Only 34% of Brazilians in a study last year said they trusted the government, an understandable reaction given recent figures showing that one in three members of Brazil’s Congress are under investigation for crimes ranging from graft to attempted homicide.

The reaction to Rosário’s big revelation wasn’t so great here in City Hall. Firstly, some councilors assumed Rosário had been caught cheating, like a lazy student using ChatGPT on schoolwork. “They didn’t get it,” he said. When they did get it, they felt duped, accusing him of being unethical by lying to them, Rosário added.

“It’s a dangerous precedent! It’s just not something you do! He should have talked to the other councilors first,” said João Bosco Vaz, 68, a councilor for the Democratic Labour Party, calling for the law to be revoked.

To be sure, the biggest pushback came from the council’s most elderly members. A week after the law was sanctioned, a group of graying public servants organized a lecture on the perils of AI.

Rosário didn’t get an invite.

Write to Samantha Pearson at samantha.pearson@wsj.com and Luciana Magalhaes at luciana.magalhaes@wsj.com