Ever since the coronavirus began to come under control, companies have been grappling with an issue that has elicited strong feelings from those in the C-suite as well as those confined to a cubicle: Should they pull all of their employees back to the office? Or should they let them work from home?

Our latest research suggests that the optimal answer is yes—and yes. A blended approach is often best.

We’ve based our assessment on a measure of corporate effectiveness created by the Drucker Institute at Claremont Graduate University. It forms the foundation of the Management Top 250, an annual ranking produced in partnership with The Wall Street Journal. Bendable Labs, a private firm, works with the institute to make the calculations and interpret them.

The institute’s model rests on the central teachings of the late management scholar Peter Drucker. It uses 34 separate indicators to gauge how companies fare across five areas, as determined through standardized scores with a typical range of 0 to 100 and a mean of 50—customer satisfaction, innovation, social responsibility, employee engagement and development, and financial strength. These categories are then combined into an overall score that reflects a company’s total effectiveness, which Drucker defined as “doing the right things well.”

The Management Top 250 for 2023 , published in December, was drawn from a larger universe of 794 companies.

Innovation and engagement

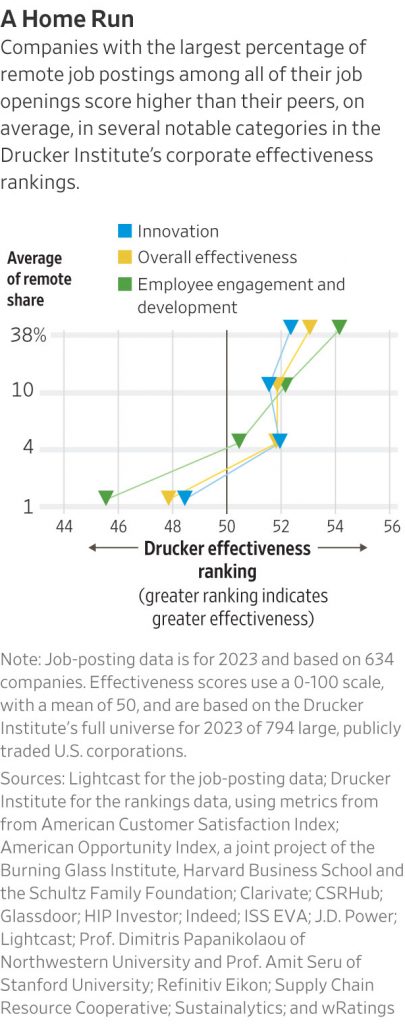

In our most recent inquiry, we examined data from Lightcast, a labor-market analytics provider, to see which companies most frequently issued remote job postings among all of their openings last year—and, in turn, how they stacked up in our innovation and our employee engagement and development categories. (It’s important to note that most jobs—caregiver, retail clerk, fast food worker, cashier, material handler and many others—can’t be done from home; only about 4 in 10 can.)

We zeroed in on those two areas—innovation, and employee engagement and development—because a host of executives have complained that working from home can negatively affect people’s ability to generate new ideas and can undermine morale and productivity.

Given these concerns, our results can seem surprising at first. When we divided the 634 companies for which Lightcast had data into quartiles, those with the highest percentage of remote postings had an average innovation score of 52.3, compared with 48.4 for those with the smallest portion of remote postings. That’s a significant gap—the difference between being in the upper third of the rankings in innovation versus the middle of the pack.

The spread for employee engagement and development was even greater: 54.1, on average, for companies with the highest share of remote postings and 45.5 for those with the lowest share.

In understanding these numbers, the key is to recognize that a “remote” posting doesn’t mean that somebody always works from home. Lightcast says that only about 17% of remote listings in 2023 spelled out that the job was “fully remote” or “home-based” or used similar language. (The other 83% were ambiguous.)

What’s remote?

Other evidence points to the fact that most “remote” jobs are actually hybrid jobs, with some days in the office mandatory. The monthly Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes—run jointly by the University of Chicago, the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Stanford University— has shown that nearly 70% of full-time employees who work from home are in a hybrid position.

Given this, it appears that the companies scoring well in the Drucker rankings have discovered a sweet spot, demanding enough in-office time to ensure that employees have a chance to interact spontaneously with colleagues, brainstorm as a group and get exposure to more senior leaders but offering enough flexibility to attract people who don’t want to schlep in five days a week.

“Two or three days in the office is probably enough to be innovative,” says Nicholas Bloom , a Stanford economist. At the same time, he adds, letting employees work from home the other two or three days helps companies “recruit and retain top talent.”

‘Best of both worlds’

Boston Scientific is a believer. The medical-device maker, which was No. 78 in last year’s rankings, views hybrid work as “the best of both worlds.” Those in such roles are expected in the office three days a week, with someone’s exact schedule hashed out with their manager.

“On in-office days, meeting in person allows employees to make tangible connections that build a sense of camaraderie and valuable growth and learning opportunities,” says Wendy Carruthers , Boston Scientific’s executive vice president of human resources. “On the days when employees are working from home, they gain the time back from not commuting to manage both their work and personal obligations. For some employees, work-from-home days can provide an ideal environment for tasks that require focus and quiet.”

At Intuit , the maker of TurboTax software, which was No. 60 in last year’s rankings, hybrid has become the “primary way of working,” says Michael Merola , vice president of places. Being in the office—especially if teams are “highly intentional” about when they’re together—fosters “serendipitous moments where employees can bounce ideas off one another and develop new and innovative solutions,” along with “a sense of inclusion and belonging,” he explains. But Intuit has also observed that working from home some days leads to “happier employees.”

“Ultimately, it’s about finding the right balance between in-office collaboration and remote flexibility to create an environment where all employees can thrive,” Merola says.

Rob Sadow , the CEO of Scoop, which helps companies benchmark their work-from-home policies and manage attendance to achieve desired outcomes, anticipates that more businesses will go hybrid. By Scoop’s count , 32% of companies are now “fully flexible,” meaning that employees are directed to work remotely all of the time or that it’s up to them whether to come into the office. But 37% are “structured hybrid,” with some amount of time in the office stipulated. (The average is about 2.5 days.)

That’s up sharply from early 2023, when just 20% of companies had “structured hybrid” setups. “I think it’s going to continue to trend that way,” Sadow says.

Fewer companies, meanwhile, are insisting that everyone be in all the time. Indeed, whenever he sees a company implementing “an aggressive RTO”—return-to-office order—Bloom takes it that they may well be in serious trouble and the CEO is trying to cast the blame on employees for working from home. “It’s a sign to sell the stock,” he says.

Considering our findings, it’s tough to argue with that. Unless employees have a mix of days in the office and at home, the chances of corporate success have become—well, rather remote.

Rick Wartzman is co-president and Kelly Tang is chief data scientist at Bendable Labs. They are also both senior research fellows at Claremont Graduate University. They can be reached at reports@wsj.com .