Last week’s violent earthquakes tore through a part of Myanmar that had already borne the brunt of a brutal campaign by the country’s military junta to root out resistance.

That double hit is now complicating relief efforts and could potentially shift the course of one of the world’s most virulent but often forgotten conflicts.

Myanmar’s current war kicked off in 2021 after the military ousted the country’s elected government in a coup. Young and mostly urban pro-democracy activists then allied with ethnic militias that have been battling government forces for decades and launched an insurgency against the ruling generals.

Myanmar’s military chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing attends a wreath-laying ceremony at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier near the Kremlin Wall in central Moscow, Russia, March 4, 2025. Alexander Zemlianichenko/Pool via REUTERS

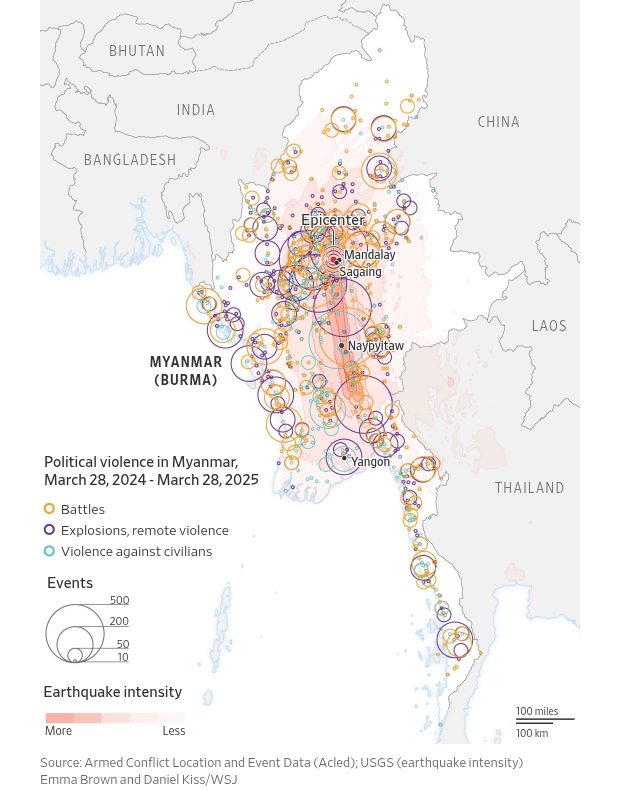

Over the past year, this collection of fighters has pushed closer into the junta’s stronghold in Myanmar’s central heartlands. The region has been devastated by Friday’s tremors , which have killed more than 3,000 people nationwide. Rebel fighters, using guerrilla tactics and often poorly armed, have asserted control over entire villages. The military responded with airstrikes and targeted attacks, burning down houses and terrorizing local populations.

By some measures, the province of Sagaing—the epicenter of the initial, 7.7 magnitude quake—has been hit harder by the war than any other region in Myanmar.

Nearly a third of the 3.5 million people that had been displaced by the fighting were in Sagaing, an agricultural region known for growing rice, pulses and watermelon. Armed Conflict Location and Event Data, or Acled, a U.S.-based nonprofit that collects conflict data, has counted more than 9,300 violent incidents in Sagaing since the start of the war. Those include battles and remote explosions such as airstrikes, drone attacks and violence against civilians.

In October, regime soldiers killed six civilians in a village called Sipa, according to Fortify Rights, an advocacy group that collected accounts of the attack. The soldiers then decapitated three of the men and mounted their heads on a bamboo fence as a warning, Fortify Rights wrote in a February report. The junta, which has previously denied some other alleged attacks against civilians, didn’t respond to a request for comment on the report.

Little is known about the damage the earthquakes have added to the previous devastation. The junta has long restricted telecommunications in areas of high rebel activity. Now, crumpled roads and collapsed bridges have made it even harder to get information.

Most of the earthquake deaths confirmed by the junta come from the hard-hit city of Mandalay, with a population of 1.2 million people, and the capital, Naypyitaw.

“These communities are already on the edge,” said Morgan Michaels, a conflict analyst at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a security-focused think tank. “Any disruption on top of that is a matter of survival.”

Several aid groups have reported heavy destruction in Sagaing’s eponymous main city, which is home to some 300,000 people. Two bridges that connect Sagaing to Mandalay were badly damaged, according to satellite images and photographs.

A Buddhist monk holds up a banknote as he donates to an injured novice at Mandalay General Hospital following a strong earthquake in Mandalay, Myanmar, April 1, 2025. REUTERS/Stringer

What is clear is that the conflict is making it harder to reach populations in desperate need of help.

On Tuesday, an aid convoy from the Red Cross Society of China came under fire from junta forces, according to the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, one of the armed groups fighting the junta. The group said the convoy was on its way to Mandalay from eastern Myanmar, through an area that had recently been targeted by junta airstrikes.

A spokesman for the junta said the military fired three warning shots when the convoy didn’t follow instructions to stop when driving through a conflict zone. A spokesman for China’s Foreign Ministry said the rescue team and supplies in Myanmar were safe.

Those disruptions add to the junta’s previous record of blocking aid to rebel-held areas—and raise concern about how earthquake relief will be distributed.

“If aid goes through the junta, we know it will never reach the people in dire need,” said Yanghee Lee , co-founder of the Special Advisory Council for Myanmar, an advocacy group, and former U.N. rights envoy to the country.

Chinese rescue workers work at the site of a collapsed building, in the aftermath of a strong earthquake, in Mandalay, Myanmar, March 31, 2025. REUTERS/Stringer

Harder to predict is the impact the disaster could have on the war itself. The National Unity Government, a shadow administration made up of politicians ousted in the coup, announced a two-week pause in fighting shortly after the earthquakes struck, saying its forces would only act in self-defense. A powerful group of rebel armies known as the Three Brotherhood Alliance also declared a month-long unilateral cease-fire.

The junta followed suit Wednesday evening, saying its forces would cease fighting until April 22. In the days after the quakes, the junta had continued to strike opposition targets from the air.

Security analysts said the disaster isn’t likely to change the dynamics of the war fundamentally. The quakes struck during a relative impasse in the fighting, which gave the junta some time to recoup after a rash of surprising, but not crippling, setbacks.

The Myanmar military’s biggest problems, according to Michaels, the IISS analyst, are a shortage of manpower and what he called the “catastrophic leadership” of junta chief Min Aung Hlaing.

A controversial conscription effort launched last year has begun to replenish its ranks. But the quakes could also stymie junta plans to stage a rebound because they damaged important state infrastructure, according to Min Zaw Oo, executive director of the Myanmar Institute for Peace and Security, a policy think tank.

Richard Horsey, senior Myanmar adviser for the International Crisis Group, said the disaster might weaken the regime, but there is still no clear path to peace. The earthquakes have “struck at its core centers of control, and a chaotic response to a crisis that affects its own inner circle will be impossible to hide,” he said.

Write to Feliz Solomon at feliz.solomon@wsj.com

Corrections & Amplifications undefined A map of political violence in Myanmar in an earlier version of this article incorrectly sized the circles representing violent events. The map has been corrected. (Corrected on April 2)