LONDON—Beijing is conducting espionage activities on what Western governments say is an unprecedented scale, mobilizing security agencies, private companies and Chinese civilians in its quest to undermine rival states and bolster the country’s economy.

Rarely does a week go by without a warning from a Western intelligence agency about the threat that China presents.

Last month alone, the Federal Bureau of Investigation said a Chinese state-linked firm hacked 260,000 internet-connected devices, including cameras and routers, in the U.S., Britain, France, Romania and elsewhere. A Congressional probe said Chinese cargo cranes used at U.S. seaports had embedded technology that could allow Beijing to secretly control them . The U.S. government alleged that a former top aide to New York Gov. Kathy Hochul was a Chinese agent .

U.S. officials last week launched an effort to understand the consequences of the latest Chinese hack , which compromised systems the federal government uses for court-authorized network wiretapping requests.

Western spy agencies, unable to contain Beijing’s activity, are raising the alarm publicly, urging businesses and individuals to be on alert in their interactions with China. But given the country is deeply entwined in the global economy, it is proving a Sisyphean task, said Calder Walton , a national-security expert at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. Western governments “are coming to terms with events, in many ways, after the events,” he said.

The Chinese government’s press office, as well as the ministries of state security, public security and defense, didn’t respond to requests for comment. Beijing has previously denied allegations of espionage targeting Western countries while portraying China as a frequent target of foreign hacking and intelligence-gathering operations.

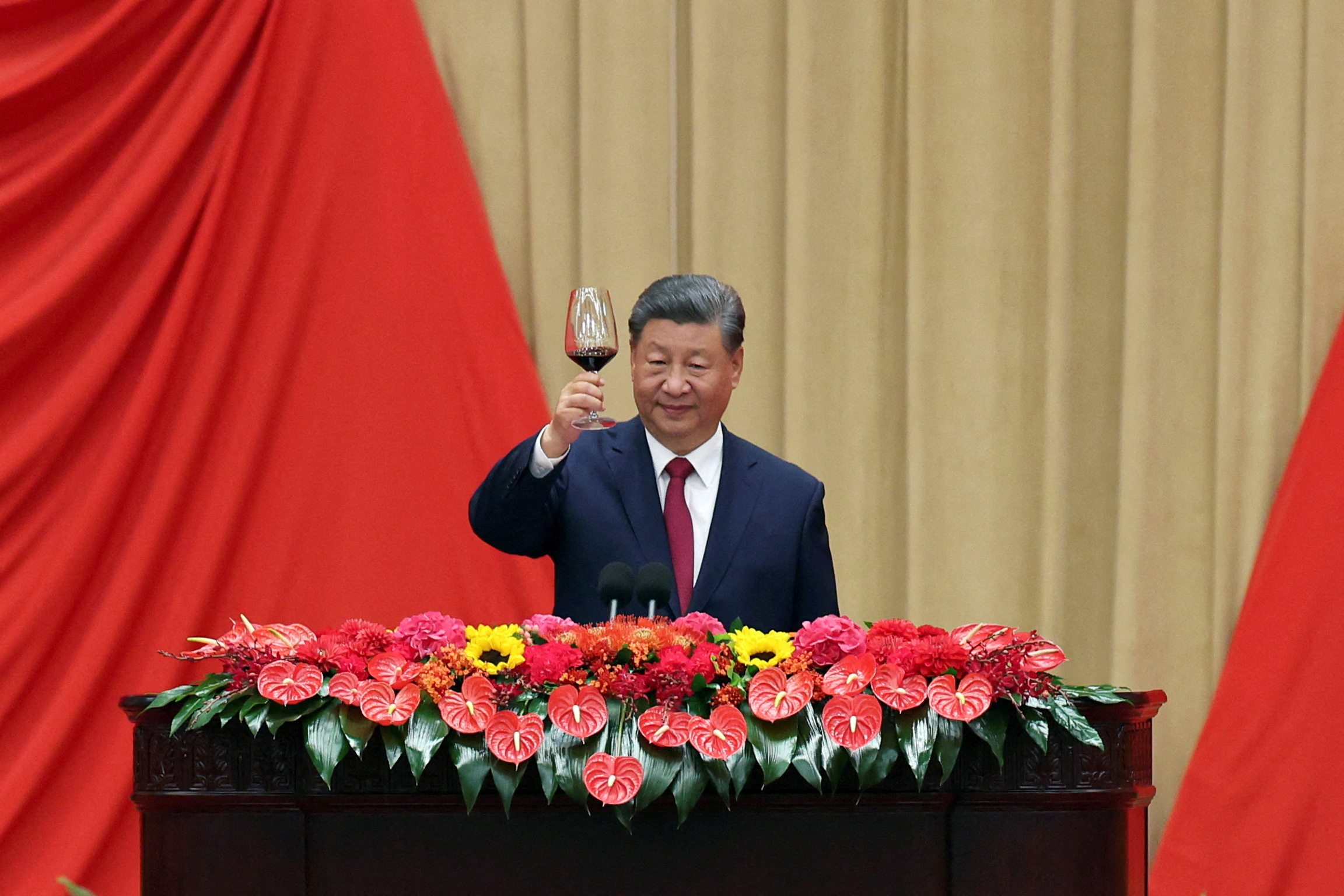

Chinese leader Xi Jinping since taking power in 2012 has increasingly emphasized the importance of national security, calling on officials and ordinary citizens alike to ward off threats to China’s interests. The result is a sweeping information-gathering effort whose scale and perseverance dwarfs that of Kremlin espionage during the Cold War and has jolted Western spy agencies.

China-backed hackers outnumber all of the FBI’s cyber personnel at least 50 to 1, according to the U.S. agency. One European agency estimates China’s intelligence-gathering and security operations might comprise up to 600,000 people. “China’s hacking program is larger than that of every other major nation, combined,” FBI Director Christopher Wray said earlier this year .

Complicating the West’s response: Unlike with autocracies such as Iran or Russia, trade with China has for decades supported Western economic growth, which in turn underpins the West’s long-term security. Most countries simply can’t afford to slap China with sanctions and throw out its diplomats. “China is different,” said Ken McCallum , the head of the U.K.’s domestic-intelligence agency, MI5.

The malign-activity risks intensifying as China’s economic growth slows under Xi’s increasingly authoritarian leadership. Beijing’s intelligence apparatus will come under pressure to pilfer the innovation needed to bolster the economy and silence critics at home and abroad, officials said. “It all boils down to the security of the regime,” said Nigel Inkster , a former director of operations at the British foreign-intelligence agency MI6.

Chinese activity ranges from the absurd to the hair-raising. In September, U.S. prosecutors alleged that five Chinese University of Michigan graduates were found in the middle of the night taking photos just feet away from military vehicles in a U.S. National Guard training exercise that included Taiwan military personnel. The men claimed to be stargazing.

Earlier this year, the U.K. government said Chinese-linked hackers had accessed the nation’s voter-registration records , which include around 40 million people’s home addresses. The U.S. government is currently probing whether a Chinese state-linked hacking group burrowed into major U.S. broadband providers, potentially accessing U.S. law-enforcement wiretaps . Intelligence officials fret China is stealing swaths of private data to train advanced artificial-intelligence models.

As China becomes more assertive militarily, including increasing support for Russia in its war in Ukraine, its covert action also poses greater threats. Xi has ordered his military to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027, the centenary of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army, according to Western officials. A war over Taiwan could draw China into conflict with the U.S., which is committed to ensuring the democratically self-ruled island can defend itself.

The FBI earlier this year said China had hijacked hundreds of routers and used them to infiltrate American water and energy networks, raising concern of a pre-emptive attack on U.S. infrastructure if Washington were to intervene in a Chinese attempt to claim Taiwan. Congress in December banned the Pentagon from using any seaport worldwide that deploys the Chinese cargo-data platform Logink , out of fear classified information could be disclosed.

China also prepositioned malware on Indian power grids amid a border dispute in 2021 and on telecommunication networks in Guam, home to a large U.S. air base, according to analysts and officials.

Central Intelligence Agency Director William Burns recently said he had visited China twice in the past year “to avoid unnecessary misunderstandings and inadvertent collisions.”

There is worry of a dangerous mishap. Spy agencies in authoritarian states often tailor information to meet their bosses’ world views. For instance, Russia’s intelligence services told Russian President Vladimir Putin that Ukraine would fold quickly after he invaded. If Xi similarly received faulty information, or didn’t believe the information he was given, China could pre-emptively strike at vital foreign infrastructure.

China doesn’t play by the old-school spy rulebooks, intelligence officials say. It doesn’t seem to care if it is caught red-handed and, unlike Russia, it rarely makes efforts to swap its spies when they are arrested.

Another factor hampers a Western intelligence response: It is hard to spy on China. Beijing’s intelligence operations are decentralized, stretching across myriad agencies and private-sector companies. They operate largely autonomously, making the system difficult to penetrate, and their methods appear haphazard, with a mix of private and state actors seemingly loosely guided by overarching aims laid out by senior officials. China also purged a whole cadre of officials working as U.S. spies a decade ago.

Underpinning China’s activity is Xi’s desire to consolidate his grip on power. He has cited the Soviet Union’s sudden collapse in 1991 as a warning of what could befall communist rule in China if ideological controls are loosened. He created a national-security commission, which first convened in 2014, to centralize control over security work, and set an expansive definition of national security that spans the party’s political dominance as well as China’s economic strength and food sufficiency.

This emphasis morphed into a fixation in recent years as Beijing clashed with Washington over territorial disputes, technological dominance and the causes of Covid-19. Further fueling paranoia were allegations by former U.S. intelligence contractor Edward Snowden that the U.S. had extensively hacked Chinese infrastructure including mobile phone networks.

“Security is the prerequisite for development, and development is the guarantee of security,” Xi told officials. “Security and development must be promoted simultaneously.”

The U.S. in 2014 accused Chinese military officers of plundering American corporate secrets through hacking—and said it was outside the bounds of traditional espionage.

The U.S. responded with tariffs and a campaign to stop its European allies from using China’s Huawei to build its next generation of telecom infrastructure.

Western democracies are trying to strike a balance now by continuing to do business with China while calling out Beijing’s spying. In May, Canadian intelligence officials said China likely tried to interfere in two past federal elections, including by busing in Chinese students to vote to secure the nomination of a preferred candidate.

Central Intelligence Agency Director William Burns has visited China over the past year to help avoid ‘inadvertent collisions.’ REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst/File Photo

Around the same time, Australian authorities sentenced a businessman with links to the Chinese Communist Party for trying to curry favor with a government minister by donating $25,000 to a local hospital. This spring, seven alleged Chinese spies were arrested during separate operations in Germany and Britain for acquiring a special laser and shipping it to China without authorization, spying on the European Parliament and targeting dissidents, respectively.

Much of China’s information-gathering activity isn’t illegal. Most of China’s researchers and businesses aren’t involved in espionage, and many are credited with contributing to important advances in innovation that benefit Western economies.

But European security officials say Chinese students and guest scientists also have become a prime conduit for Chinese espionage in the West. In the past, security officials kept a close eye on Chinese researchers who had studied at one of the “ Seven Sons of National Defense ,” a nickname for top Chinese universities with strong links to the military. Recently, the officials say, spies masquerading as researchers have grown better at hiding their tracks. One example is students who initially enroll in language or literature courses and then switch to quantum computing or other sensitive areas.

More than 20,000 people in the U.K. alone have been approached by Chinese agents on LinkedIn since 2022 in attempts to get them to hand over sensitive information, according to MI5, the U.K.’s domestic spy agency.

MI5 has been touring universities warning them about collaborations with Chinese-backed consultancies or universities, which could inadvertently hand over valuable intellectual property. Spy agencies can’t “disrupt our way out of that challenge,” McCallum, the head of MI5, said recently.

Write to Max Colchester at Max.Colchester@wsj.com and Daniel Michaels at Dan.Michaels@wsj.com