The Russian economy, surprisingly resilient through two-plus years of war and sanctions, has suddenly begun to show serious strains.

The ruble is plunging . Inflation is soaring , and President Vladimir Putin told the Russian people this week that there isn’t any reason to panic.

The catalyst for the change in economic fortunes was a decision by the Biden administration to ratchet up sanctions on Russia’s Gazprombank , the last major unsanctioned bank that Moscow uses to pay soldiers and process trade transactions, as well as more than 50 other financial institutions.

Gazprombank had been carved out of previous rounds of sanctions to allow allies in Europe to pay Russia for critical supplies of energy. It was a vital conduit for inflows of hard currency in exchange for Russia’s exports.

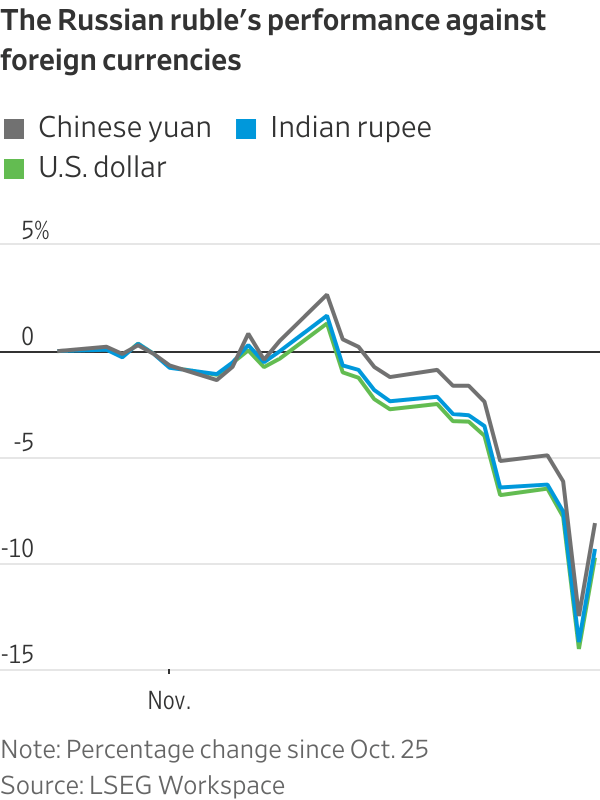

The ruble fell to a 32-month-low this week, and remained near its weakest point since the days after Moscow invaded Ukraine, according to LSEG data, trading for about 108 rubles to the dollar.

The free fall was stopped after Russia’s central bank intervened in currency markets late Wednesday. The bank said it would stop buying foreign currency for the rest of the year, which it does when the government has an oil-and-gas surplus, a move that should help alleviate a critical shortage of hard currency available to businesses and consumers.

Putin said Thursday that “the situation is under control and there are certainly no grounds for panic.” Economy Minister Maxim Reshetnikov said that concerns about how the sanctions were affecting Russia’s foreign trade were behind the ruble slump.

“It is obvious that adaptation to the new anti-Russian sanctions will be required, including in terms of changing banking mechanisms and channels for currency inflows to the Russian market,” he said on Friday.

The new sanction measures could gum up Russia’s already constrained trade routes with other countries, Russian officials and analysts say.

It is a pivotal time for the nearly three-year-old war. Russia is advancing along the front line, assisted by North Korean troops and Iranian weaponry . President-elect Donald Trump has promised to end the war in Ukraine quickly, leaving the outlook for current and future sanctions on Russia unclear.

In targeting Gazprombank, a state-controlled lender that began as an energy banking hub but has in recent years grown in importance in other cross-border payments, Washington is trying to stifle one of the last major links to the Western financial system.

Russia has traded more in its own currency and so-called friendly currencies , such as China’s yuan and India’s rupee. Russian businesses have also found workarounds by using cryptocurrencies, or by bartering. But access to dollars remains critical.

After the measures were announced, Turkey said it would talk to the U.S. to try to secure a waiver so it can continue paying Gazprombank for natural-gas imports from Russia, its top supplier. Hungary, one of the few European countries still relying on Russian gas, said that it would also look for solutions.

The sanctions on Gazprombank are having a “chilling effect, where traders, exporters and foreign banks are trying to figure out where their liabilities are, so it’s rational there’s a bit of a panic,” said Rachel Ziemba , an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security, a Washington-based think tank focused on foreign policy. “But we may see in a couple weeks that new routes open up.”

Russia’s economy took a sharp blow in the months after Moscow launched its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. But heavy government spending and a wholesale reorientation of the economy toward the war effort returned the economy to growth. Huge payouts to soldiers and cheap mortgages helped keep households afloat.

Military spending hit a post-Soviet high this year and is planned to rise to more than $120 billion next year, making up over 30% of total spending for the year.

But the stimulus has had dangerous side effects. Most notably, inflation is running at more than twice the central bank’s target . The bank has jacked up interest rates to 21% this year, which has done little so far to cool the overheating economy. A record labor shortage, as working-age men go to the front, has further fueled inflation.

Now, the plummeting ruble threatens to further increase the cost of imports. Consumer inflation is already running at close to 9% this month, according to official data. An alternate measure compiled by market-research firm Romir found that the average cost for everyday goods and services was up 28% in mid-November compared with last year.

Tatiana Orlova , lead emerging-markets economist at Oxford Economics, expects Russia’s central bank to raise rates to 23% next month. She also expects the government to reimpose capital controls requiring exporters to repatriate more of their foreign-currency earnings, which boosts demand for rubles.

Those efforts, along with a drop in imports after the holidays, might stabilize the ruble’s value. But higher interest rates will start to weigh more heavily on the economy next year, she said, leading to a recession in 2026. Parts of the economy that aren’t being bolstered by government support, such as agriculture and transport, are contracting.

“The economy is probably at a turning point,” Orlova said. “This very tight monetary policy is driving the economy toward recession.”

Few think Russia is on the precipice of a more serious economic crisis, but the difficulties are expected to mount the longer the war persists.

“The policy trade-offs will become more and more challenging,” said Elina Ribakova , nonresident senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Russia is likely to continue eroding its economic prospects by giving priority to the war effort at the expense of healthcare, education and other nonmilitary areas, she said.

Ordinary Russians were rattled by this week’s drop. They still watch the dollar exchange rate closely, and the ruble’s slide past 100 rubles per dollar was a psychologically important threshold for gauging the health of the economy. Against the Chinese yuan, the ruble has fallen nearly 10% this month.

On the social-media app Telegram, which is popular with Russians, a user pleaded: “Please tell me that everything will be okay, I feel sick.”

The Russian central bank’s official account responded, “Everything will be fine.”

Write to Georgi Kantchev at georgi.kantchev@wsj.com and Chelsey Dulaney at chelsey.dulaney@wsj.com