BRUSSELS—European countries are waking up to Russia’s danger, but the cost of building robust defenses able to withstand a potential U.S. pullback is so great that it threatens Europe’s post-Cold War social model.

With presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump questioning America’s future in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and Russian forces on the offensive in Ukraine, European leaders are warning of an existential threat to the continent’s security.

War nearby and disputes with the U.S. have exposed gaps in Europe’s military capabilities that would take years to plug even if governments make military spending a political priority, which they haven’t done for decades.

European Union leaders meeting Thursday plan to address the bloc’s defense vulnerabilities and its ambition to expand its defense industry . Painful decisions lie ahead.

Boosting Europe’s security would require increasing defense outlays just as many European countries are cutting budgets to cope with high debt levels and weak economic growth . Achieving the military spending that some politicians and experts say is needed would force European members of NATO to start reversing big post-Cold War increases in social spending.

“You have to rearrange the social contract,” said Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis , who has warned that Russia will eventually attack NATO countries if it isn’t defeated in Ukraine .

Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis speaks to members of the media as he attends a European Union Foreign Ministers’ meeting in Brussels, Belgium March 18, 2024. REUTERS/Johanna Geron

Europe would need at least 20 years to build a European force capable of reversing a Russian invasion of Lithuania and nearby parts of Poland without the U.S., according to an analysis by the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a think tank, in 2019.

The cost, IISS said, would be $357 billion, equivalent to more than $420 billion in today’s prices. Europe’s NATO allies are projected to spend $380 billion on defense this year.

While vast amounts of Russian equipment have been destroyed in Ukraine, many European officials say Moscow could rebuild its military within a few years of the war’s end. NATO has meanwhile depleted its own stocks of weapons to keep Ukraine armed.

Because militaries need years to plan, equip and train forces, European governments face immediate and tough spending trade-offs.

“It comes down to the political will in combination with an ability to explain to the public what it is we really have to do,” said Anna Wieslander, director for Northern Europe at the Atlantic Council, a think tank in Washington. “The closer to Russia you get, the easier it seems to be.”

Europe in recent years has started reversing military cuts made after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. During the Cold War, many NATO members spent roughly 3% of gross domestic product on defense. Those outlays plunged in subsequent years.

After Russia seized the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine in 2014, NATO members agreed to lift their spending to 2% of GDP by this year. Many experts believe European defense expenditures must reach 3% of GDP if the U.S. starts to disengage.

The swing would be enormous for some countries.

For Belgium to buy merely enough ammunition to fight an invasion for a few weeks, it would cost more than $5 billion, said retired army Lt. Gen. Marc Thys. The kingdom is one of NATO’s lowest military spenders, at less than 1.2% of GDP last year.

When Thys joined the military in the 1970s, Belgium could deploy 50,000 men to Germany. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine two years ago, Belgium agreed to send 300 troops to Romania. “We had to pull out all the stops,” he said.

Thys said most Western European governments will face the “growing pains” of learning to synchronize “equipment coming in, people coming in, building infrastructure and training them.”

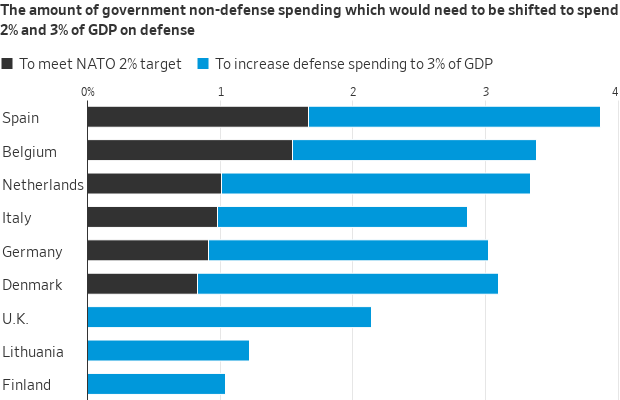

Most European countries can hit 2% military spending by squeezing other government outlays by less than 1 percentage point, according to a recent study by Germany’s Ifo Institute for economic research.

But to reach 3% would mean shifting several percentage points of government spending to defense, Ifo said.

Britain has long spent 2% of GDP on defense but has a target of 2.5%, contingent on economic conditions.

To reach 3% of GDP, Britain would need to boost military spending by more than $40 billion, said Ben Zaranko, senior research economist at the U.K.’s Institute for Fiscal Studies. That is twice what Britain spends on its justice system.

“I think generally, if we want to spend much more on defense and we don’t want a bigger state, the government has to start removing state responsibilities,” Zaranko said.

Europe’s defense cuts since the Cold War generated a peace dividend of around $2 trillion, according to Ifo.

Ifo calculates that although European NATO countries’ military spending has returned to 1991 levels based on 2023 prices, social spending has more than doubled in that period, to consume half of government spending. That includes entitlement plans such as rising pension costs in an aging continent, which are politically hard to adjust.

That fiscal pressure has left Europe dependent on Washington for vital military capabilities. Among those are air defense, midair refueling, combat engineering, artillery and ammunition, experts say. Europe struggles to move its forces across borders without U.S. help.

Washington also provides sophisticated intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance assets needed for fast reaction to threats. It dominates the digitization of militaries that allow forces to connect and communicate securely during conflicts.

“We have armed forces that look good and shiny, and platforms you can present for export…but aren’t prepared for war,” said Gustav Gressel, a senior policy fellow working on defense at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Europe’s shortfalls have shown up repeatedly in smaller conflicts since the Cold War. Britain and France ran out of precision bombs fighting in Libya in 2011.

Some European countries are already shifting. Poland is spending 4.2% of GDP on defense, it is building up its forces and has embarked on a huge procurement drive for cutting-edge tanks, helicopters, rocket launchers and jet fighters.

Sweden and Finland, which spend heavily on defense, have joined NATO , strengthening its grip in the Baltic region near Russia. NATO accelerated its buildup of troops and equipment on its eastern flank after Russia attacked Ukraine and Europe has started narrowing some shortfalls of critical U.S.-provided military equipment.

But faced with elections, most governments struggle to address military funding. Germany’s shaky coalition government, which holds elections next year, hasn’t said how it would lift spending back to 2% or above once its special defense fund of $109 billion runs out in 2027.

In Britain earlier this month, when the government’s pre-election budget barely lifted military spending in real terms, a couple of ministers went public with calls to raise spending now.

European military planners struggle to even start addressing how NATO might operate without a high level of U.S. support, said Edward Arnold, a research fellow for European security at the Royal United Services Institute in Britain.

“In the official planning sessions, there’ll be no change,” he said. “But when they go for coffee in the breaks, they’ll probably all say ‘God, if we were doing this without the Americans, what would it actually look like?’ ”

Write to Laurence Norman at laurence.norman@wsj.com