SHEFAYIM, Israel—Five-year-old Uriah Brodutch was asked recently by his kindergarten teaching assistant whether he’d had any dreams lately. Yes, the boy said, he had dreamed about men taking him away from his home and killing other people.

Palestinian gunmen had kidnapped Uriah, his older brother Yuval, 9, and sister Ofri, 11, on Oct. 7, 2023 , along with their mother, Hagar, and Abigail, a now 4-year-old girl from their kibbutz who had turned up at their family home that morning covered in her father’s blood. Both of her parents were dead.

The Brodutch family and Abigail were held captive for nearly two months before they were released. More than a year later, they all remain scarred by the trauma.

Uriah’s father, Avihai, was wounded fighting gunmen that day but escaped from the kidnappers. His young son, Avihai said, recounted his violent dream “like it’s just a fact of life. He wasn’t crying. It just seems normal for him.”

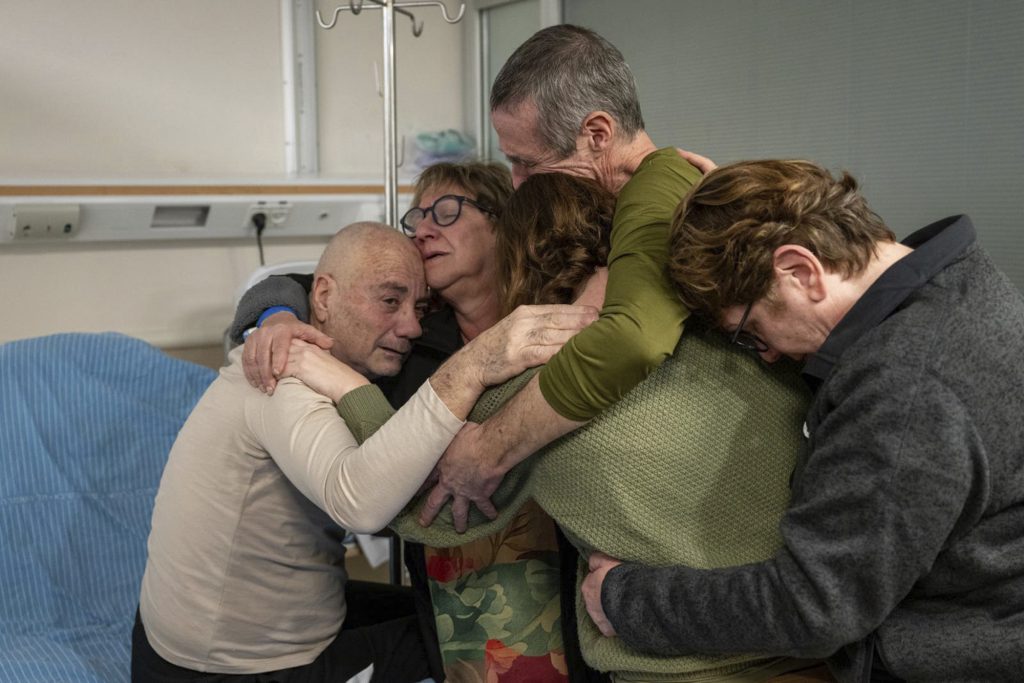

Luis Har, left, hugs his relatives after being rescued from captivity in the Gaza Strip, in Ramat Gan, Israel, on Feb. 12, 2024. (Israeli Army via AP)

“So many people died around him, and he was taken to Gaza,” Avihai said. “They saw bodies everywhere, and houses in flames. A lot of my friends and neighbors who we knew well had their families killed. So it’s a part of our life now: death.”

On Saturday, three more hostages , including American-Israeli Sagui Dekel Chen, 36, were freed by militant groups in Gaza as part of ongoing talks to end the war . Their release marked the end to one part of their ordeal—but just the beginning of what previously released captives described in interviews as a long and wrenching process of recovery.

Some 250 people were taken hostage on Oct. 7, including 40 children. About 70 remain in Gaza, although Israeli officials think more than 30 of them are dead . Those believed to be alive have thus far endured nearly 500 days in captivity. Former hostages, family members and therapists said the lives of those who are released will never be the same.

The Oct. 7 attack, which killed some 1,200 people, and Israel’s subsequent invasion and bombing of Gaza have produced widespread suffering, including for untold numbers of Palestinians who have lost loved ones and seen much of the strip reduced to rubble. More than 47,000 Palestinians have been killed in Gaza since the war began, according to local health authorities, who don’t say how many were combatants.

Many of the Oct. 7 hostages who remain in Gaza are being held in tunnels and—based on the accounts of those released —are likely to be half-starved and to have endured psychological and in some cases physical abuse. Two hostages released a week ago told the family of a remaining hostage, 24-year-old Alon Ohel, that he has been living shackled in an underground tunnel, with shrapnel embedded in his eye, and subsisting on just one pita bread a day.

Interviews with three hostages who were released more than a year ago, as well as with family members of others and psychologists who are treating former captives, indicate that many released hostages struggle to recover. Recovery might prove even tougher for those held longer.

Eli Sharabi, a 52-year-old who looked gaunt and frail upon his release a week ago, told a crowd in Gaza before his handover that he was looking forward to seeing his wife, Lianne, and daughters Noiya, 16, and Yahel, 13. Sharabi was unaware that gunmen had killed all three in the family home on Oct. 7, along with the family dog.

Israeli captive, Eli Sharabi, who has been held hostage by Hamas in Gaza since October 7, 2023, stands on a stage escorted by Hamas fighters before being handed over to the Red Cross in Deir al-Balah, central Gaza Strip, Saturday Feb. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

Physical and psychological

Former hostages said their ordeals showed them how much they were capable of surviving, but left them struggling with physical and psychological aftereffects. Many haven’t returned to their homes and will try to rebuild their lives in new places, usually farther away from the Gaza border.

“I don’t sleep much at night anymore. My head is filled with thoughts,” said Luis Har, an Argentine-born 71-year-old abducted from kibbutz Nir Yitzhak, one of several that came under attack that day. “Many times, a noise—a motorcycle or an ambulance—takes you right back. You have to tell your body that you are here, you aren’t there.”

Mia Schem, a 22-year-old French-Israeli citizen whose hostage video was one of the first to emerge in the days after the attack, and who has become a celebrity in Israel, said she is riding an emotional roller coaster. Some days her ordeal feels like a movie or a dream that happened to someone else. Other days, she said, “the feelings of Gaza won’t go away.”

“People think you are out, you are safe, and that it’s over,” she said. “But it’s not. Every day is a battle to get up and fight.” She said she vividly recalls piles of dead bodies at the Nova music festival, where nearly 400 people were massacred, and the harrowing cries of women she couldn’t see but that she believes were being raped.

Moran Stela Yanai, a 41-year-old jewelry designer seized during the Nova festival and held in dark spaces for 51 days, said she can’t tolerate being indoors or in a closed room for more than a few minutes. When she isn’t outside, she said, she spends most of her time on the patio of her Tel Aviv apartment.

“The porch is my anchor,” she said. “I know that no matter what happens in a day, I will get to the porch, it’s my safe space.” On her wrist, she wears a silver bracelet that says “warrior.”

Yanai said she can’t understand why she survived while another hostage she had befriended, Carmel Gat, 40, was murdered by their captors as the Israeli army closed in on the tunnel where they were being held.

“We are like a mirror image,” Yanai said. “She did yoga. I did Pilates. We both tried to communicate with our captors. So I ask God, ‘Why did you choose her and not me?’ That’s the question that will go with me the rest of my life. I sometimes feel like a mistake was made. Maybe she was a better person. Maybe she should have been saved.”

Yanai lost much of her hearing in captivity and now wears hearing aids. Both of her legs were broken during her kidnapping, and she has had multiple surgeries on them since her release.

Schem, the French-Israeli former captive, was shot in the arm while trying to escape the Nova music festival. Her elbow is destroyed. Four surgeries later, her right arm is a few inches shorter than her left. She said she developed epilepsy after nearly 50 days of being held alone in the same room as her armed male captor, where she managed only snatches of sleep. “My body is still tense,” she said.

Some hostages and their families described a euphoria upon release that lasted several weeks. “You feel like you took a drug. Everyone is back together,” said Avihai, the father of the little boy named Uriah. His wife spent her entire captivity thinking Avihai had been killed in the fighting that day. “But after a while,” he said, “things start to fall apart.”

His family, he said, learned little by little that many of their closest friends and neighbors, who regularly come over to his house for weekly barbecues, were dead.

Har, the Argentine-Israeli rescued by Israeli commandos after 129 days in captivity, said he didn’t watch the news for several days afterward, so he didn’t know until later about the mass killings at the Nova music festival. The news weighed on him.

Former hostages said they suppressed their emotions during captivity to survive. “We were punished for crying, punished for laughing, punished for missing your parents,” said Yanai. “They want you to be a robot, to act according to their needs. One time I cried and I was beat up for it. So when he came and shouted at me for crying, I just stopped. I was like, ‘OK.’”

Complex trauma

Therapists working with released hostages said that many, including the children, are suffering from complex trauma, a condition caused by exposure to multiple and repeated traumatic events.

Ofrit Shapira Berman, a trauma expert at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, said those suffering from it have “the most profound sense that you have to surrender yourself in order to save your life.” Many of those suffering from it, she said, have difficulty connecting with other people.

All the former hostages interviewed said they had trouble relating to people who didn’t have some connection to Oct. 7. “Most of us, we have different friends now,” Yanai said. “It’s not like I fought with my old friends. It’s just that those friendships kind of faded away. I feel like I can’t have a normal conversation anymore.”

It can take several weeks or months to develop a normal relationship with food and water, said former hostages and their families. While captive, each member of the Brodutch family received only one pita bread a day, which they would tear into small pieces to try to make last the entire day. When little Uriah was in the hospital after his release, he would stash his bread under his pillow to eat later, his father said.

“As a Jew, you grow up on stories from the Holocaust and the images of these emaciated bodies,” said Avihai. “And now your family has gone through this.”

Images of the three captives released a week ago angered many Israelis, with some relatives and Israeli officials saying they looked as if they had been held in concentration camps.

Many former hostages have found a sense of purpose in helping lobby for the release of the remaining captives and helping their families cope. “I have this image in my mind that when the last hostage is released, I am going to turn off the TV, fly to Thailand and sit on the beach for three weeks and cry my ass off,” said Yanai.

Therapists who have treated children kidnapped on Oct. 7 said some began wetting their beds again. In the Brodutch household, all three kids have been sleeping with one or both parents each night.

“Before, they would hear sirens [signaling a rocket attack] and go inside,” said Avihai. “But there was never fear. Now, there’s a lot of fear. If a door slams, or there is a loud noise outside, they worry people are going to come in, and knock down their doors.”

The Brodutch children, who missed a year of school, still struggle to attend more than three days a week. Yuval, the 9-year-old, rarely makes it a full day before wanting his mother to pick him up.

At school, Yuval has a tutor who works with him one-on-one. “The other kids are all super nice to him,” said his father. “They have been amazing. But he just doesn’t want to be in the classroom.”

Most of the children who were hostages don’t want therapy because they want to try to forget what happened, said Iris Gavrieli Rahabi, a psychotherapist who helped found First Line Med, which gives free counseling to former hostages and other survivors of Oct. 7. But there are signs the children are struggling with guilt, she said.

Gavrieli Rahabi said one child hostage, after weeks of captivity, turned to her mother and said, “You know, mommy, we were caught because I was crying.” The mother reassured her that wasn’t the case, that the assailants knew they were home because the hot chocolate on the stove was still warm.

The psychotherapist said that another boy, months after he was released, suddenly told his father he had told the kidnappers his father’s real name. He said the captor was nice to him and asked him to tell him, but that he was sorry. “Many kids are carrying things that we don’t know,” Gavrieli Rahabi said.

Yanai, the jewelry designer, said she vowed during captivity that she wouldn’t let her abductors ruin her life. “When I am not doing well, they win,” she said. “If I can recover fully, I win.” She also decided she would try to become a mother, despite being single at age 41. “That’s going to be my revenge.”

Write to Carrie Keller-Lynn at carrie.kellerlynn@wsj.com and David Luhnow at david.luhnow@wsj.com