For a microcosm of how the war in Ukraine has warped Russia’s economy, look no further than a carton of eggs.

The grocery staple has been in short supply in recent months and prices have skyrocketed, prompting Russians from Belgorod to Siberia to form lines reminiscent of Soviet times. President Vladimir Putin has publicly apologized, blaming the egg shock on the government. Last month, a poultry-farm boss known as “the Egg King” survived an assassination attempt shortly after authorities started investigating his farm due to high prices.

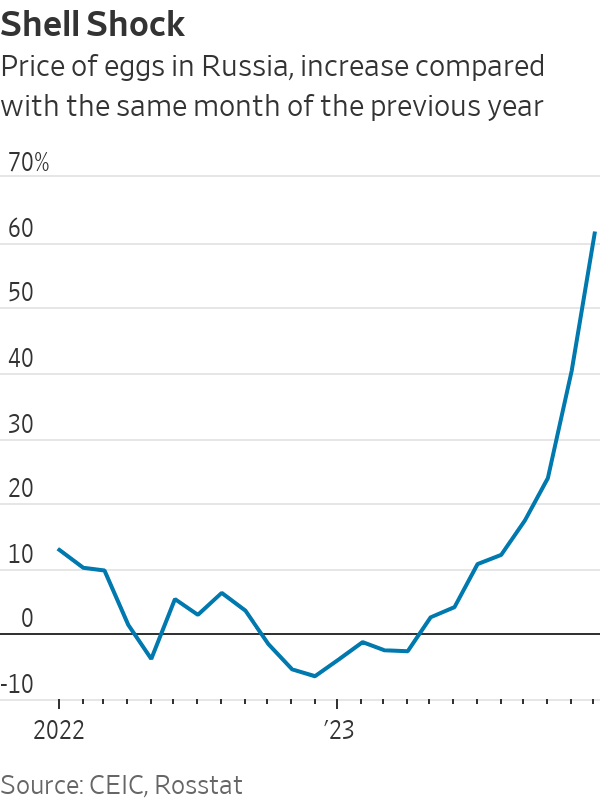

Behind the soaring price tag—up around 60% in December from a year earlier, according to data released Friday—is a convergence of factors symptomatic of the economy’s travails.

Western sanctions have hurt the poultry industry by scrambling supply chains for farm equipment previously coming from Europe. The weak ruble has made imports of feed and veterinary products more expensive while a labor crunch has left some suppliers without enough farm hands. Booming government spending, meanwhile, has increased wages, boosting demand for food and other goods.

All of which makes the egg shock a manifestation of the imbalances building in Russia’s war economy.

The country confounded expectations last year by recording respectable growth as Moscow boosted military production and doled out subsidized loans to consumers and businesses. Yet such largess has left the economy running too hot.

As a result, annual inflation ended up 7.4% last year, nearly double the central bank’s goal, and the government’s mortgage programs have fueled a housing bubble. Economists now expect growth to slow as the central bank raises interest rates and sanctions continue to bite.

“The government looks like a bunch of firefighters who run from one small fire to another with a bucket because they cannot eliminate the underlying inflation problem,” said Alexandra Prokopenko, a former Russian central bank official who is now a nonresident scholar at the Berlin-based Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

As the war in Ukraine enters its third year, the egg crisis shows how Russia is struggling to balance clashing economic imperatives—financing the war, placating popular discontent and keeping the economy balanced, including through stable prices.

“It’s an impossible trilemma,” said Prokopenko. “Achieving the first two goals requires higher spending, which leads to high inflation, which prevents the achievement of the third goal.”

Inflation is a growing concern for Putin ahead of presidential elections slated for March. A crackdown on opposition parties and all independent media should ensure he scores an easy victory, but the Kremlin sees elections as a way to legitimize the president’s rule, requiring a degree of genuine popular enthusiasm.

Instead, voters were reminded of Soviet-era food shortages as long lines of customers waiting to buy eggs began forming ahead of the New Year’s holidays. Some supermarkets in Siberia and occupied Crimea sold eggs individually, for about 12 rubles, or 13 cents, each. One local deputy gifted cartons of eggs to his employees for the holidays.

Telegram—the social network that is widely used in Russia—quickly filled up with hundreds of posts of people worrying about egg availability, exchanging tips on where to buy them cheaper or cracking jokes.

“It’s time for a choice: eggs or caviar,” one post said. Another user wrote: “You are all bitcoin, bitcoin, but I told you that you need to invest in eggs.”

After Putin pinned the egg-price shock on the government, saying it didn’t secure enough imports in time, authorities sprung into action. Russia boosted egg orders from Turkey, Belarus and Azerbaijan and removed import duties on the product. The Ministry of Economy didn’t respond to a request for further comment.

Authorities also launched antitrust investigations into egg and chicken producers, including the Tretyakovskaya poultry farm in the Voronezh region, owned by Gennady Shiryaev, the Egg King. On Dec. 27, after news of the probe became public, a shooter fired at least twice on Shiryaev’s Volkswagen SUV, though Shiryaev escaped unscathed. The Tretyakovskaya poultry farm didn’t respond to a request for comment.

One factor that could prove difficult to correct is a shortage of vaccines after Western sanctions complicated their import.

“There is nothing to vaccinate with, so birds get sick,” said a St. Petersburg-based veterinarian. “These are quite fragile agricultural animals, and because they are kept in heaps, when one bird gets sick, almost all of them get sick.”

Eggs are a relatively small part of the consumer basket but people tend to notice sharp price rises, said Tatiana Orlova, lead emerging markets economist at Oxford Economics, which can in turn entrench inflation expectations—something central banks are concerned about.

Russia’s central bank last month raised its key interest rate to 16%, more than double where it stood in June, to curb rising consumer prices. Higher rates act as an economic brake, with the latest consensus by Focus Economics, which collects banks’ forecasts, expecting gross domestic product growth to slow to 1.4% this year from close to 3% last year.

Experts predict that the egg inflation will stabilize soon but that prices will remain high. Other countries, including the U.S., have shown that after big price rises, consumer sentiment continues to suffer long after inflation stabilizes.

In Russia, new imports can’t compensate for the structural problems on the market and the current price is adequate and fair for the product, Galina Bobyleva, general director of poultry union Rosptitsesoyuz, told Russia’s parliamentary newspaper last week.

For some Russians, such as Andrey, a 33-year-old software engineer living in Moscow, the egg episode is just one facet of a dysfunctional economy.

“Russians will pay for the consequences of isolation out of their own pockets for a long time to come,” he said.

—Kate Vtorygina contributed to this article.

Write to Georgi Kantchev at georgi.kantchev@wsj.com