The Cold War’s end promised relief from nuclear nightmares. Long-adversarial governments agreed to eliminate warheads and collaborated to stop the spread of atomic weapons. That promise is now slipping away.

Russian President Vladimir Putin last month touted new rules on using nuclear arms, offering Moscow’s latest signal of readiness to use atomic weapons in its defense. North Korea’s nuclear arsenal is expanding. Iran is close to developing usable nuclear weapons , prompting fears of a Middle East arms race.

One of the two critical U.S.-Russian nuclear-arms-control treaties has collapsed. The other, which caps how many nuclear weapons Russia and the U.S. deploy, expires in early 2026. A pledge made by declared atomic powers during the Cold War to strive for disarmament looks less realistic than ever.

Roughly 60 years ago, President John F. Kennedy warned that by 1975 the world could have 15 to 20 nuclear powers. His fears were inflated: there are only nine today.

Still, the global nonproliferation system is in greater peril than at any time since the Cold War, says United Nations International Atomic Energy Agency, or IAEA, Director-General Rafael Grossi . The threat of a nuclear confrontation, which a decade ago seemed fanciful, is no longer unimaginable.

Russian President Vladimir Putin last month touted new rules on using nuclear arms, offering Moscow’s latest signal of readiness to use atomic weapons in its defense. Alexander NEMENOV / AFP/Visualhellas

“The shared consensus among great powers on the importance of nonproliferation—which was critical to building and sustaining the nonproliferation regime since the 1960s—has eroded,” said Eric Brewer, a former director for counterproliferation at the National Security Council, now at the Nuclear Threat Initiative think tank. “I think at a minimum we’re going to end up in a world with more countries that are capable of building nuclear weapons.”

After the Berlin Wall fell, the U.S. and Russia cooperated to deactivate more than 3,000 strategic nuclear warheads located in the former Soviet republics of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine. By 2012, Russia and the U.S. each held fewer than 5,000 warheads. In 1988, they had more than 41,000 and 23,500 respectively, according to the Federation of American Scientists.

South Africa, which had developed a small nuclear arsenal, became the first—and still only—country to scrap its nuclear weapons in the early 1990s. A decade later, Libya agreed to end its nuclear program. Iran, in the wake of the U.S. invasion of neighboring Iraq, agreed to start negotiations over its nuclear research.

Nonproliferation faced some setbacks. Pakistan tested its first nuclear weapon in 1998, and North Korea did so in 2006.

Efforts to contain nuclear threats have centered on the 1970 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, or NPT. It codified a decision made by the two superpowers that limiting the spread of nuclear weapons was more important than seeking advantage by each giving its allies the bomb.

The NPT, which today has 191 signatories, commits countries without a bomb to using nuclear energy for peaceful purposes and grants the U.N.’s IAEA oversight powers. It includes a pledge by nuclear-weapons states to work in good faith to reduce their arsenals.

As tensions have grown among the U.S., China and Russia in recent years, the consensus around nonproliferation has frayed. Officials say Iran could be just months away from building a nuclear weapon, and Saudi Arabia has said it would follow suit if that happens. Top officials in South Korea and Turkey have talked about their countries going nuclear.

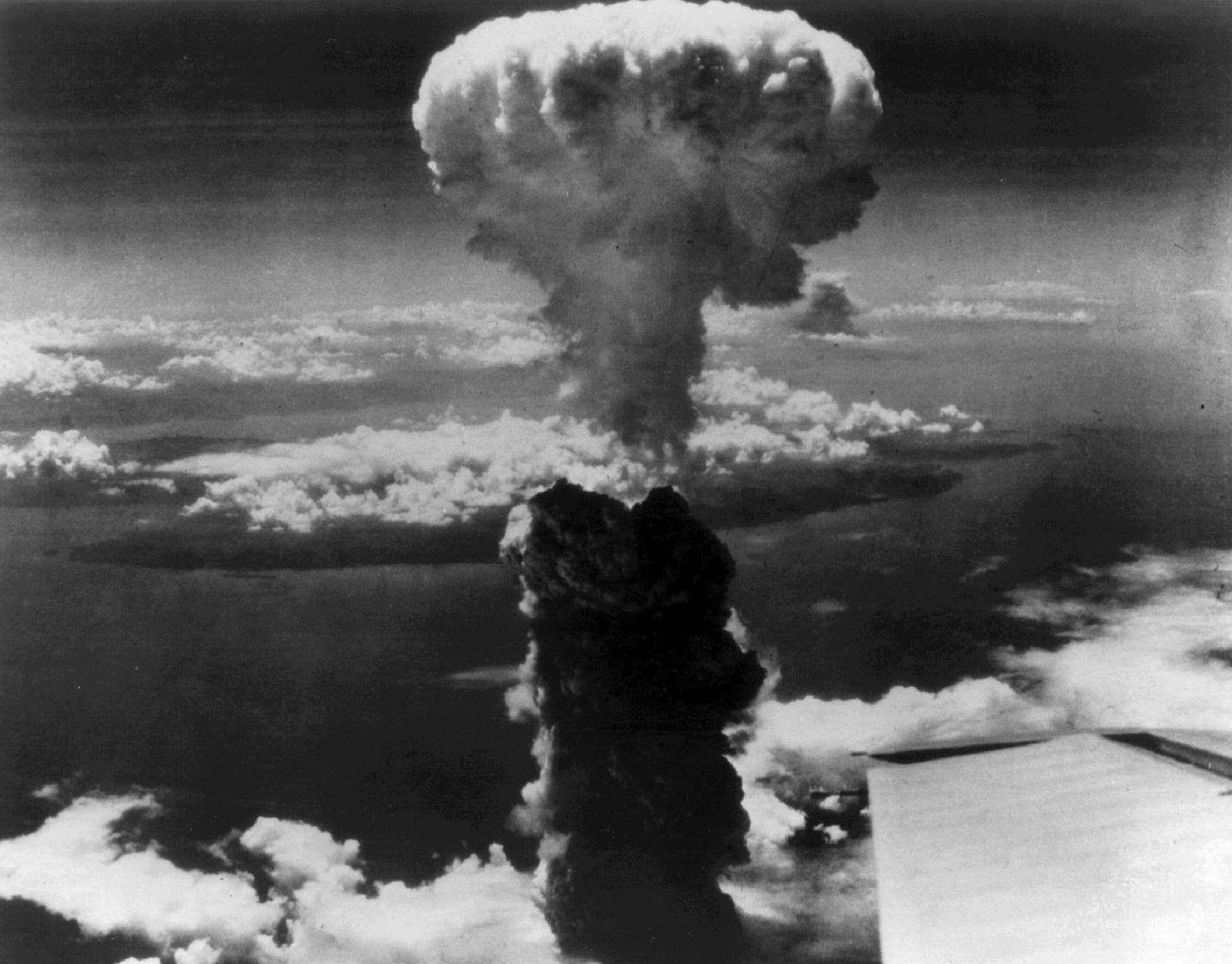

Russia’s actions since its invasion of Ukraine have raised the first real specter of nuclear-weapons use in decades. The invasion itself represented a violation of terms of a 1994 pact, under which Ukraine handed over Soviet nuclear weapons on its territory to Russia.

Russia has repeatedly pointed to its nuclear weapons as a means of defense, although Western intelligence agencies have detected no real steps to prepare for nuclear use.

Last month, while the U.S. and its allies debated allowing Ukraine to fire longer-range weapons into Russia, Putin announced a new nuclear doctrine which made the grounds for potentially using nuclear weapons more explicit.

Russia also has recently agreed to place nuclear weapons under its control in Belarus, which borders several North Atlantic Treaty Organization members, including Poland.

Moscow has openly flouted nuclear-related sanctions on North Korea, as part of a growing partnership in which North Korean leader Kim Jong Un has sent millions of artillery rounds to Russia.

Nikolai Sokov, former Russian diplomat and now senior fellow at the Vienna Center for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, said the weapons transfer to Belarus mirrors the nuclear sharing the U.S. has undertaken with allies. He said Putin’s nuclear talk has escalated because of concerns that the West wasn’t taking his red lines seriously enough. He said the nuclear-doctrine change was another case of Putin’s signaling.

“I quite honestly did not see any serious change in the nuclear doctrine,” he said.

Others see Russia’s actions as a dangerous loosening of the taboo around the use of nuclear weapons.

“Russia used its nuclear weapons as a cover for the 2022 aggression, when it wanted to prevent Western countries from coming to support of Ukraine,” said Lukasz Kulesa, director of proliferation and nuclear policy at the U.K.’s Royal United Services Institute think tank.

Former NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg accused the Kremlin last month of employing “a pattern of reckless Russian nuclear rhetoric.” NATO is pushing back by talking more openly about its annual Steadfast Noon nuclear drill, aiming to show both adversaries and citizens that it is prepared for conflict if needed. That exercise started Monday.

In this new environment, the dangers of a nuclear arms race are accelerating.

China’s nuclear expansion appears to be the most rapid and Beijing has so far refused negotiations on its plans. The Department of Defense has estimated that China’s current nuclear arsenal of roughly 500 weapons will reach 1,500 by 2035, putting Beijing on a par with Russia and the U.S. The U.K. announced in 2021 a raise in its cap on the number of nuclear weapons.

Some experts believe Russia and the U.S. may reach an informal understanding to keep deployed nuclear warheads capped once the New Start agreement ends in 2026. But, Washington also faces pressure to boost its nuclear stockpile. A congressionally appointed commission last year recommended that the U.S. prepare to expand its nuclear forces to deter the twin threats from China and Russia.

The U.S.’s future nuclear posture is only one of the debates swirling around nuclear weapons in Washington.

The growing focus on China’s military threat in Washington is tapping into long-existing debates about how committed the U.S. should be to its alliances in Europe and Asia—and in what form.

North Korean leader Kim Jong-un looks on during the test of what KCNA described as a new tactical ballistic missile, in this picture obtained by Reuters on September 19, 2024, in North Korea. KCNA via REUTERS

Earlier this year, Elbridge Colby, a Pentagon official under former President Donald Trump , suggested that the U.S.-South Korea defense alliance should be reshaped to allow Washington to focus on Beijing. He said that South Korea should have all options on the table when it considers how to counter the North Korean threat. Last month, South Korea’s new defense minister used similar language on whether the country should pursue the bomb.

The Biden administration in 2023 sought to eliminate that option. It gave Seoul a greater voice in consultations on a potential American nuclear response to a North Korean attack in return for Seoul swearing off its own nuclear weapons.

Some members of Congress have criticized the Biden administration’s plan to share nuclear technology with Saudi Arabia as part of the White House’s efforts to establish diplomatic relations between the kingdom and Israel. They say any potential agreement should prevent Saudi Arabia from being able to enrich uranium domestically.

Matthew Kroenig, senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and one of the participants in the Congress’s nuclear strategy review, argues that despite the strains on the global nonproliferation system, the U.S. has the tools to shore it up.

“We focus on the problem children like Iran and North Korea but for the most part, 190 countries are following it,” he said of the NPT. “I do think a lot of it is in our hands…And I think the big one is extended deterrence and can we get our nuclear strategy in order and credibly assure our allies?”

The IAEA’s Grossi is less sanguine. Today’s increasingly tense global environment makes “the attraction of nuclear weapons very strong,” he said last month. “It’s a difficult moment, indeed.”

Write to Laurence Norman at laurence.norman@wsj.com