Switzerland thought it came to terms with its Nazi-assisting past after harrowing probes in the 1990s led its two largest banks to pay more than $1 billion restitution to Holocaust victims. Documents unearthed in bank archives show it might have been at least in part a whitewash. A cache of client files stamped “American blacklist,” a designation for those financing or trading with Nazis or Axis partners, was recently found by independent investigators probing Credit Suisse, one of Switzerland’s biggest banks and now part of UBS.

The investigators, who studied dusty ledgers and pored over microfilm that hadn’t been part of earlier reviews into the dark chapter, found something else, too: signs of a coverup.

In the 1990s, two panels studied Swiss banks’ World War II-era activities after anger erupted over Holocaust victims’ unreleased funds.

But the investigators now taking a fresh look found Credit Suisse withheld crucial information.

They located several Nazi-linked accounts that were discovered by the bank in the 1990s but never disclosed to investigators. They also turned up new details of an operational account controlled by high-ranking Nazi SS officers and a Swiss intermediary that was allegedly used to move and store looted assets.

The findings came to light in a probe overseen by an independent ombudsman, Neil Barofsky. The former U.S. prosecutor, who is a partner at law firm Jenner & Block, was hired by Credit Suisse in 2021 after the Simon Wiesenthal Center found information on possible Nazi clients that hadn’t previously been disclosed.

The Senate Budget Committee got involved two years ago, when Credit Suisse fired Barofsky from the probe. Bank executives played down what he had found and felt he had overstepped lines it wanted around the investigation. The committee has jurisdiction over the State Department’s Office of the Special Envoy for Holocaust Issues, which seeks to secure compensation for Nazi-era wrongs.

Barofsky was reinstated in late 2023, following UBS’s emergency rescue of Credit Suisse. In a December 2024 letter to the Senate, reviewed by The Wall Street Journal, Barofsky said Credit Suisse and new owner UBS have fully opened their archives and have assigned more than 50 people to work on the probe.

“The investigation has identified scores of individuals and legal entities connected to Nazi atrocities whose relationships with Credit Suisse had either been previously unidentified, or for which the relationship had been partially identified but the full nature of the bank’s involvement has not yet been reported publicly,” Barofsky wrote in the letter.

“UBS is committed to contributing to a fulsome accounting of Nazi-linked legacy accounts previously held at predecessor banks of Credit Suisse,” said a bank spokesperson.

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D., R.I.) and Sen. Chuck Grassley , (R., Iowa) spearheaded the effort in the Senate. “Credit Suisse hid additional evidence of Nazi ties for years, and even tried to conceal information from our congressional investigation,” Grassley said.

Recent photos taken by a visitor to one of the bank’s archives in Zurich shows the scale of the task: rooms full of pallets of boxes stacked from floor to ceiling, and an array of old ledgers, computers and hard-drive disks all storing client records.

Buried in storage were around 3,600 boxes from the “Inf department” containing information about clients, including ones who were on the U.S. wartime blacklist for furthering the Nazi cause.

Barofsky described the Inf department files as akin to “know your customer” details that banks keep on their clients. A preliminary search against 99 known Nazis and affiliates produced 13 name matches. Numerous files bore the American blacklist stamp, he said, which his team hadn’t seen before in other Credit Suisse archives.

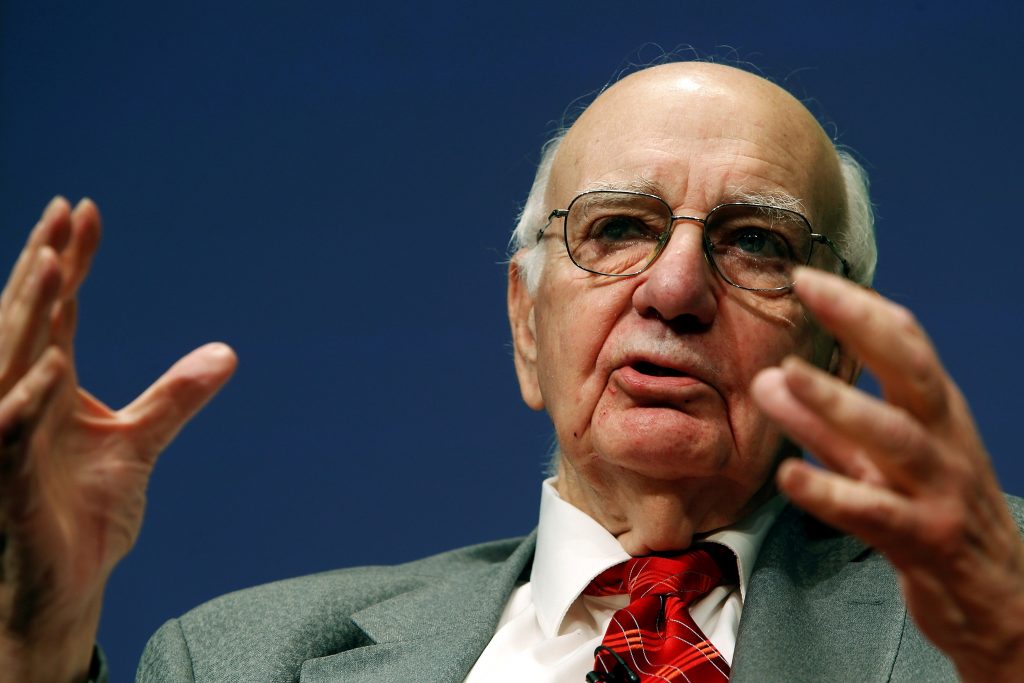

Paul Volcker, oversaw the group tasked in the 1990s with finding the value of dormant or looted accounts.

Some portions of the Inf department files were included in earlier reviews but were never scanned, indexed or systematically incorporated into those probes, Barofsky said in the letter to Congress. That work is now ongoing.

While conducting the new probe, which included interviews with former bank employees who worked on the 1990s research, Barofsky found indications the bank covered up its role by not always sharing what it knew.

Internal comments by bank executives in the 1990s on one of the panel’s draft reports said the report was “rather sanitized,” but best left as is. Credit Suisse’s general approach to outside investigations was to share only requested information and not offer additional insights, Barofsky said his team was told.

Key information and relevant accounts weren’t shared then with the outside panels, including information about the account controlled by officers of the Nazi SS— Adolf Hitler ’s elite paramilitary unit—and a Swiss intermediary. The businesses that used the accounts promoted the regime’s economic aims, seizing businesses from Jewish owners and relying on forced labor at concentration camps.

A registry card for the SS-linked account was found in the 1990s and was flagged to higher-ups, according to the former employees and documents and emails that were discovered in the new probe. Credit Suisse as recently as April 2023 said bank historians hadn’t previously associated the registry card with the account in question, including in the 1990s reviews.

When asked by one of the panels in 2001 about the account, Credit Suisse said it had no documents indicating a business relationship with the SS holding company, leading the panel to conclude documents must have been destroyed.

After outcry in the mid-1990s over Holocaust victims’ missing assets, a group overseen by Paul Volcker , the former Federal Reserve chairman, sent auditors deep into the banks’ files to find dormant or looted accounts.

A second group, assembled by the Swiss parliament and headed by historian Jean-François Bergier , trawled through bank archives to study Switzerland’s Nazi-financing.

The two panels’ main findings were that Swiss bankers routinely turned a blind eye to Nazi theft of Jewish assets during the war and often obstructed families’ later efforts to reclaim their money. Neither review claimed to encompass all wartime accounts or to give a definitive result.

In the 1990s probes, Credit Suisse identified 14 likely Nazi clients. UBS said it found one account for a former Reichsbank president and another opened by an SS officer’s widow decades after the war.

The two banks agreed to pay $1.25 billion to Jewish families who had been denied money in Swiss accounts and to surviving slave laborers or their heirs. Many Jewish organizations supported the settlement at the time.

Barofsky told the Senate his team of investigators expects to issue a final report around early 2026.

Write to Margot Patrick at margot.patrick@wsj.com

Corrections & Amplifications undefined The Senate Budget Committee got involved in the Credit Suisse case two years ago. A previous version of this article incorrectly said it was the Senate Banking Committee. (Corrected on Jan. 4)