Giant investment companies are taking over the financial system.

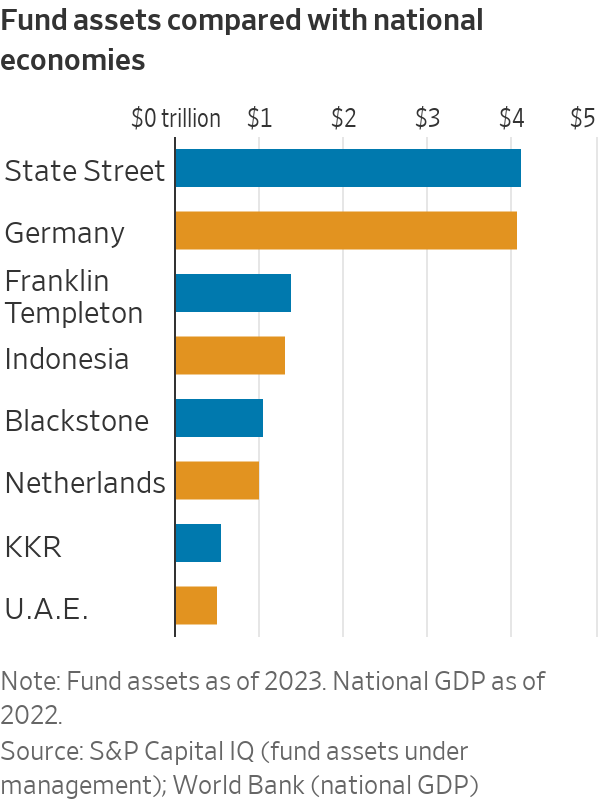

Top firms now control sums rivaling the economies of many large countries. They are pushing into new business areas, blurring the lines that define who does what on Wall Street and nudging once-dominant banks toward the sidelines.

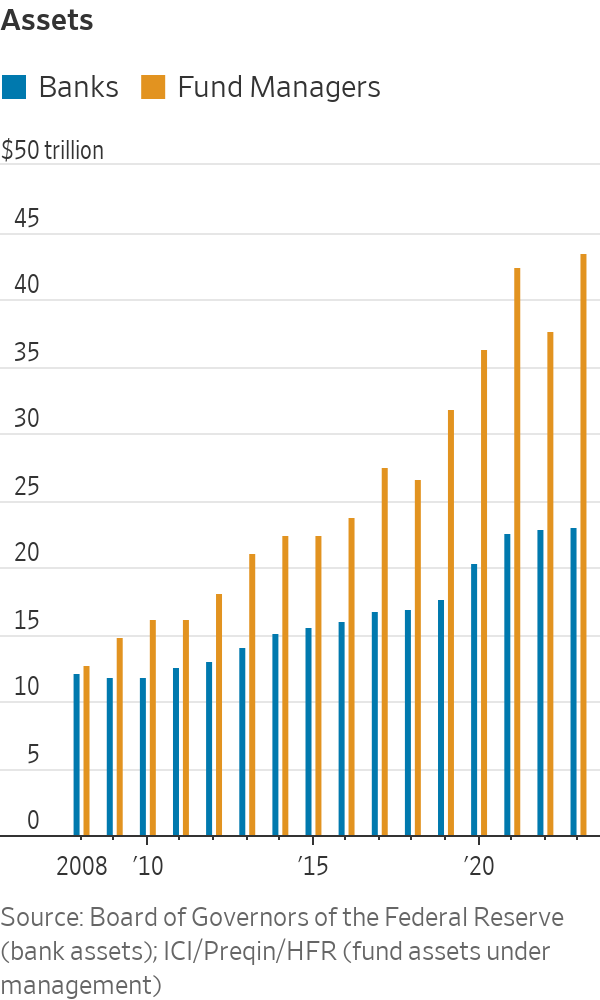

Today, traditional and alternative asset managers control twice as many assets as U.S. banks, giving them increasing control over the purse strings of the U.S. economy.

The firms—such as Blackstone , Franklin Templeton , BlackRock and KKR —are becoming more complex and more similar to one another all at once. Investors say this creates risks that markets have never encountered before.

Fund-manager executives insist the expansion, as striking as it is, remains in its early innings. Good news for them because fast growth is bringing them vast wealth, especially in private, or “alternative,” investing. Private equity has minted more billionaires than any other industry in recent years, according to data from Forbes.

Here’s a look at how the field is shifting:

Trillion-dollar titans

Huge fund-management companies are bulking up by offering new types of products to capture market share. The biggest are evolving into financial supermarkets, mostly for institutions and the wealthy, but increasingly for middle-class investors as well. Banks consolidated similarly in the decade leading up to the financial crisis .

Private-equity and private-debt funds , such as Apollo Global Management and Blackstone, mostly manage money for institutions, but are increasingly selling products to individual investors. Mutual-fund behemoths, including BlackRock , are growing bigger still by building or buying private-fund operations.

Asset managers are also supplanting banks as lenders to U.S. companies and consumers and intertwining with the insurance industry .

Top private-fund executives say they require long-term client commitments, making them more stable than deposit-dependent banks such as Silicon Valley Bank .

“We’re moving into a gray area as asset-management businesses move into different silos of financial services,” said Tyler Cloherty , a managing director at consulting firm Deloitte who advises fund managers. “The big question I’m getting is ‘What do we do around getting alternatives to retail clients?’ There’s a lot of complexity there.”

The growth spurt came out of the 2008 financial crisis, when new regulation curtailed investing and lending by banks, making room for fund managers to expand. Central banks kept interest rates low for most of the following decade, driving investors out of savings accounts and Treasury bonds and into managed funds.

Blurring the lines

In 2008, U.S. banks and fund managers were roughly neck and neck at about $12 trillion of assets. Today, traditional asset managers, private-fund managers and hedge funds control about $43.5 trillion, nearly twice the banks’ $23 trillion, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of data from the Federal Reserve, HFR, ICI and Preqin.

Large banks have responded by becoming more like fund managers, beefing up investment teams. Goldman Sachs reported this month revenue of about $4 billion from asset and wealth management in the first quarter, twice the earnings from its storied investment-banking division.

Large banks have responded by becoming more like fund managers, beefing up investment teams. Goldman Sachs reported this month revenue of about $4 billion from asset and wealth management in the first quarter, twice the earnings from its storied investment-banking division.

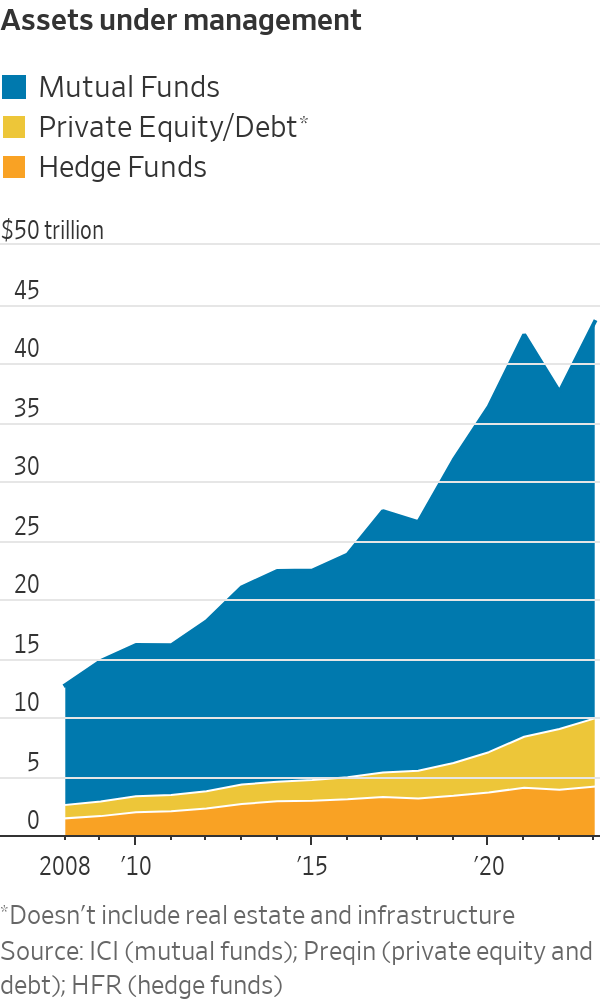

Public-fund managers, meanwhile, became huge, mostly by offering low-fee mutual and exchange-traded funds that track indexes. Four of the biggest—BlackRock, Fidelity, State Street and Vanguard—control about $26 trillion, equivalent to the entire annual U.S. economic output.

But over the past four years, private equity and debt fund assets doubled to almost $6 trillion, far outpacing the 31% growth rate for public funds. The firms began selling private-credit funds to their core clients—pension funds and endowments that had maxed out on private equity . The fund managers also made inroads with new investors, such as insurance companies and individuals.

As the funds grow bigger, their founders make more money. Private-equity fund managers took 41 spots on Forbes magazine’s list of U.S. billionaires published this month, more than any other profession. The investors make up 5.5% of all the country’s billionaires, almost twice the 3% they comprised just 10 years ago.

The surge could continue. KKR Co-CEO Scott Nuttall —a 2022 addition to the Forbes billionaires list—told shareholders at a meeting this month that KKR will double the money it controls to $1 trillion by 2029. Only 2% of wealthy individuals currently invest in alternative funds and that will jump to 6% by 2027, he said.

Rival Marc Rowan , CEO of Apollo Global Management, says his firm will increase its roughly $650 billion under management to $1 trillion by 2026. Blackstone, which crossed the $1 trillion threshold in July, launched this year its first private-equity fund targeted at individual investors. The fund has raised about $3 billion so far, the fastest start ever for a retail fund by the firm, a person familiar with the matter said. Blackstone has raised more than $100 billion through private debt and real-estate funds aimed at individuals.

Public-fund managers are much bigger than their private counterparts, but also less profitable after years of lowering fees to gain market share. A growing number, including Franklin Templeton and T. Rowe Price , are buying alternative managers to boost profits .

Scott Nuttall, co-CEO of KKR, says the firm will double assets under management to $1 trillion in five years. PHOTO: SARAH BLESENER FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The trend hit a fever pitch in January, when BlackRock struck a deal to buy Global Infrastructure Partners for $12.5 billion, the highest price ever for an alternative-asset manager, according to Dealogic. If the acquisition goes through as expected, it will mint another six billionaires for the Forbes list from among Global Infrastructure’s founding partners.

Other traditional fund managers have taken a slower—and less expensive—approach, building their own private-fund businesses.

Regulating private equity for the masses

Neuberger Berman , a traditional fund manager born out of Lehman Brothers’ collapse, has about one-third of its $463 billion in investments in alternatives, up from about 10% a decade ago. The employee-owned firm raised the bulk of the assets from institutional investors.

“Much of the future growth will be driven by individuals who don’t have either the experience or professional staff to help them,” said Neuberger Chief Executive George Walker . The onus is on fund managers to educate the new buyers and provide them with well-diversified products to reduce risk, he said.

Neuberger launched in 2021 a product it calls Access that pools dozens of private funds and their investments to give clients with low buy-ins a diversified portfolio. The fund doubled in size over the past year to about $1 billion.

Bond-fund powerhouse Pacific Investment Management Co., which manages about $2 trillion, has increased alternative investments to $165 billion from $10.7 billion in 2010, a company spokeswoman said. TCW , another bond-fund manager , doubled alternative investments over the past four years to $20 billion, about 10% of total assets, a person familiar with the matter said. Both firms hired portfolio managers away from private-equity and hedge-fund firms to help staff the efforts.

Regulators are tackling titanic fund managers from several angles. The Securities and Exchange Commission approved in August new rules for private funds requiring more investor disclosures and proscribing side deals with institutional clients.

Rising sales of private funds to individuals come as leveraged buyouts by private equity returned 8% last year, the lowest level since 2011, according to Preqin. Higher interest rates have made it harder for the funds to sell companies they own and more expensive to buy new ones.

Traditional fund managers are being scrutinized over their outsize influence in shareholder votes. In November, an interagency regulator passed a rule allowing large fund managers to potentially be regulated as systemically important institutions, as large banks are. Still, the decision only reinstates an Obama-era measure overturned by the Trump administration.

Write to Matt Wirz at matthieu.wirz@wsj.com

Corrections & Amplifications undefined In 2008, U.S. banks and fund managers both controlled about $12 trillion of assets. An earlier version of this article incorrectly said it was $12 billion. (Corrected on April 22)