Meta Platforms safety staff warned last year that new paid subscription tools on Facebook and Instagram were being misused by adults seeking to profit from exploiting their own children.

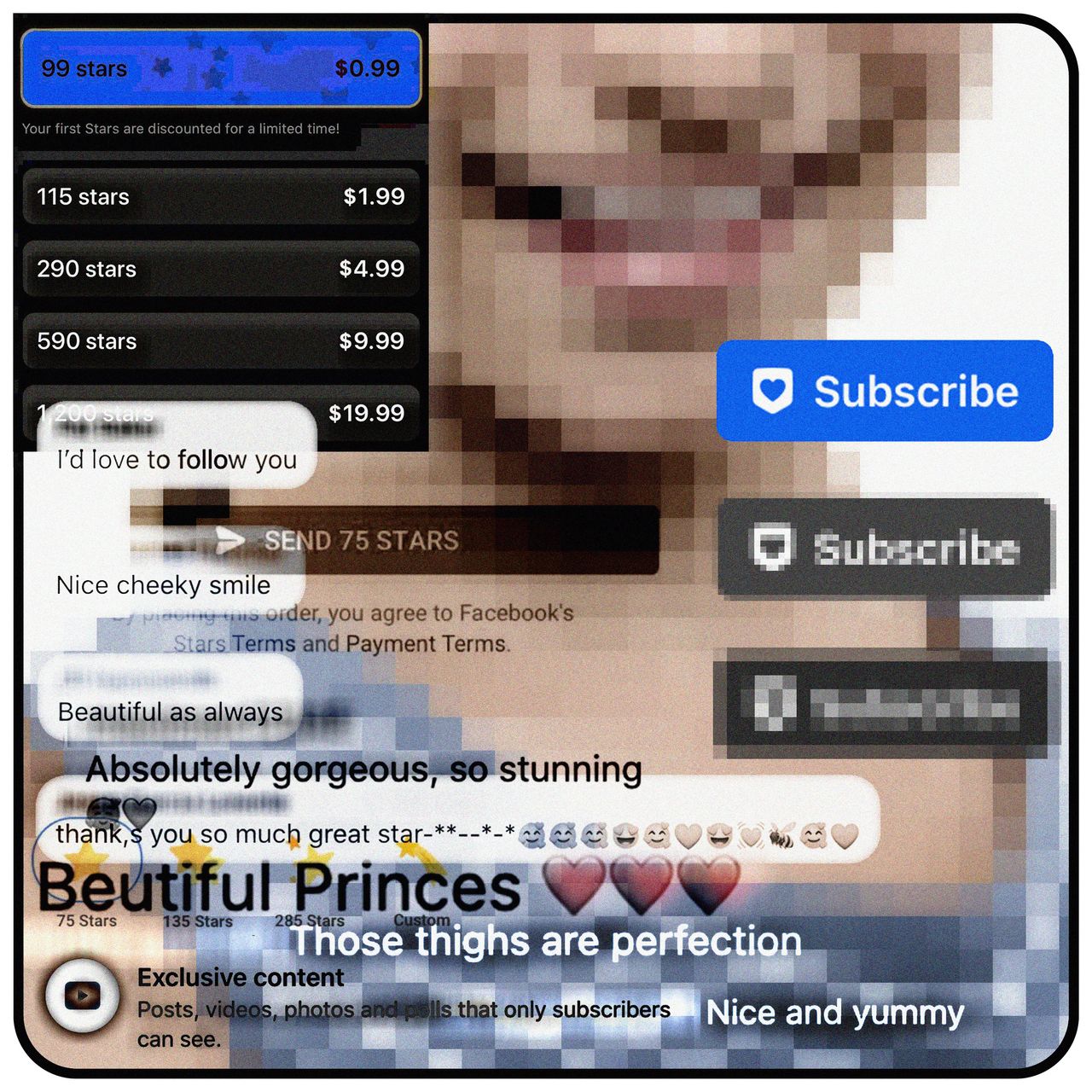

Two teams inside Meta raised alarms in internal reports, after finding that hundreds of what the company calls “parent-managed minor accounts” were using the subscription feature to sell exclusive content not available to nonpaying followers. The content, often featuring young girls in bikinis and leotards, was sold to an audience that was overwhelmingly male and often overt about sexual interest in the children in comments on posts or when they communicated with the parents, according to people familiar with the investigations, which determined that the payments feature was launched without basic child-safety protections.

While the images of the girls didn’t involve nudity or other illegal content, Meta’s staffers found evidence that some parents understood they were producing content for other adults’ sexual gratification. Sometimes parents engaged in sexual banter about their own children or had their daughters interact with subscribers’ sexual messages.

Meta last year began a broad rollout of tipping and paid-subscription services, part of an effort to give influencers a financial incentive for producing content. Only accounts belonging to adults are eligible to sell content or solicit donations, but the platform allows adults to run or co-manage accounts in a child’s name.

Such child-modeling accounts drew untoward interest from adults. After Sarah Adams, a Canadian mother and social-media activist, brought attention to a group of Instagram accounts selling bikini photos of teen and tween girls last spring, Meta’s own reviews confirmed that parent-run modeling accounts were catering to users who had demonstrated pedophilic interests elsewhere on the platform and regularly used sexualized language when discussing the models. According to the reviews, Meta’s recommendation systems were actively promoting such underage modeling accounts to users suspected of behaving inappropriately online toward children.

The reviews didn’t find that all parent-run accounts were intentionally appealing to pedophilic users, and some parents of prominent young models have said that they viewed subscriptions as part of a valuable online profile even if some of the interest they drew was inappropriate.

The Meta staffers found that its algorithms promoted child-modeling subscriptions to likely pedophiles, and in some cases parents discussed offering additional content on other platforms, according to some people familiar with the investigations.

To address the problems, Meta could have banned subscriptions to accounts that feature child models, as rival TikTok and paid-content platforms Patreon and OnlyFans do, those people said. The staffers formally recommended that Meta could require accounts selling subscriptions to child-focused content to register themselves so the company could monitor them.

Meta didn’t pursue those proposals, the people said, and instead chose to build an automated system to prevent suspected pedophiles from being given the option to subscribe to parent-run accounts. The technology didn’t always work, and the subscription ban could be evaded by setting up a new account.

While it was still building the automated system, Meta expanded the subscriptions program as well as the tipping feature, called “gifts,” to new markets. A Wall Street Journal examination also found instances of misuse involving the gifts tool.

Meta said such programs are well monitored, and defended its decision to proceed with expanding subscriptions before the planned safety features were ready. The company noted that it doesn’t collect commissions or fees on the payments to subscription accounts, giving it no financial incentive to encourage users to subscribe. The company does collect a commission on the gifts to such creators.

“We launched creator monetization tools with a robust set of safety measures and multiple checks on both creators and their content,” spokesman Andy Stone said. He called the company’s plans to limit likely pedophiles from subscribing to children “part of our ongoing safety work.”

A review by the Journal of some of the most popular parent-run modeling accounts on Instagram and Facebook revealed obvious failures of enforcement. One parent-run account banned last year for child exploitation had returned to the platforms, received official Meta verification and gained hundreds of thousands of followers. Other parent-run accounts previously banned on Instagram for exploitative behavior continued selling child-modeling content via Facebook.

In two instances, the Journal found that parent-run accounts were cross-promoting pinup-style photos of children to a 200,000-follower Facebook page devoted to adult-sex content creators and pregnancy fetishization.

The logo of Meta Platforms’ business group is seen in Brussels, Belgium December 6, 2022. REUTERS/Yves Herman

Meta took down those accounts and acknowledged enforcement errors after the Journal flagged their activities and the company’s own past removals to Meta’s communications staff. The company often failed, however, to remove “backup” Instagram and Facebook profiles promoted in their bios. Those redundant accounts then continued promoting or selling material that Meta had sought to ban until the Journal inquired about them.

Some of the parent-run child accounts on Instagram reviewed by the Journal have received extensive attention in forums on non-Meta platforms. Screenshots from those forums provided to the Journal by a child-safety advocate show that men routinely reposted Instagram images of the girls and discussed whether specific parents were willing to sell more risqué content privately.

In a number of instances, users swapped tips on how to track down where specific girls live. “I swear I need to find her somehow,” one user wrote after describing a sex fantasy involving one 14-year-old.

Meta has struggled to detect and prevent child-safety hazards on its platforms. After the Journal last year revealed that the company’s algorithms connect and promote a vast network of accounts openly devoted to underage-sex content, the company in June established a task force to address child sexualization on its platforms.

That work has been limited in its effectiveness, the Journal reported last year. While Meta has sought to restrict the recommendation of pedophilic content and connections to adults that its systems suspect of sexualizing children, tests showed its platforms continued to recommend search terms such as “child lingerie” and large groups that discussed trading links of child-sex material.

Meta’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg testifies during the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on online child sexual exploitation at the U.S. Capitol, in Washington, U.S., January 31, 2024. REUTERS/Nathan Howard

Those failures have drawn the attention of federal legislators and state attorneys general .

A recent Journal review of accounts subscribing to child-modeling content found that many had explicitly sexual usernames. Those with publicly viewable accounts appeared to mostly follow sexual cartoons and other adult content along with children. One subscriber to child-model accounts posted on his account a video of what he said was himself ejaculating.

The Journal also found that Meta’s gifts program, available to accounts with at least a thousand followers, also featured unsavory activity. Some popular accounts sought donations via the program for curating suggestive videos of young girls stretching or dancing that they had culled from other sources, exposing those children to a mass audience that plastered the posts with suggestive emojis and sexual comments. In a number of cases the “send gift” button was featured on posts promoting links to what they indicated were child sexual-abuse videos.

In addition to problematic parent-run minor accounts, the Journal found numerous examples of others offering subscriptions and gifts for content against Meta’s rules. One titled “sex porn video xvideos xnxx xxx girl sexy” purported to livestream adult videos. A 500,000-user Spanish-language group called “School Girls” also was offering subscription content.

Meta removed both after they were flagged by the Journal, and said that it had recently begun screening accounts that sell subscriptions for indications of suspicious activity involving children using a tool called Macsa, short for “Malicious Child Safety Actor.” The company says it will also screen buyers of such content for pedophilic behavior, but that work isn’t yet finished.

Other examples of violative accounts allowed to seek payments posted exploitative images of pedestrians being crushed by vehicles and a sex scene implying rape. These videos had in some cases millions of views.

Meta’s Stone said that the presence of the send gift button didn’t prove that the company had actually paid money to the accounts soliciting tips. Videos that successfully elicit cash donations are subject to an additional layer of review, he said.

To encourage content production on their platforms, Meta and other social-media companies have encouraged aspiring creators to solicit funding from their followers, either via cash “tips” and “gifts” or recurring subscription payments. The platforms generally take a cut of those payments. Meta has said it wouldn’t take a cut on subscriptions through at least the end of 2024. The company collects commissions on gift payments to creators.

Such creator payments are a significant departure from the core advertising business of major social-media networks, bringing them into competition with more specialized platforms built for creators to sell digital content, such as Patreon and OnlyFans.

Both of those platforms have policies restricting subscriptions and tipping for content involving children in ways that Meta doesn’t. Patreon requires minors to have an adult guardian’s permission to open an account, and bans underage modeling accounts.

OnlyFans, which caters to both adult-content creators and those devoted to nonsexual material, bans minors from its platform entirely on safety grounds, using both artificial intelligence and manual review to remove even wholesome images that feature children. Under the company’s policies, a cooking influencer would be barred from showing her family in the kitchen.

TikTok told the Journal it bans the sale of underage modeling content on both TikTok marketplace and via its creator-monetization services. A spokeswoman for YouTube said it wouldn’t inherently ban subscriptions to child-modeling content, but noted that it doesn’t allow communication between accounts and their followers, which Meta promotes as a core feature of its subscription product.

Write to Jeff Horwitz at jeff.horwitz@wsj.com and Katherine Blunt at katherine.blunt@wsj.com