TOKYO—It was 18 minutes of terror, confusion and determination to get out alive.

A blaze was spreading in the back of the plane and smoke was filling the cabin. The realization began to dawn on the 367 passengers: They had only minutes to save themselves from a fiery death. A child cried out, “Please, open the door!”

Joseph Hayashi, 28, was in seat 27B, returning from a ski vacation in northern Japan.

“People were trying to get away from the jet engines because they were worried that the jets would explode,” said Hayashi, who is from Dallas and works in finance in Tokyo. “I’m not a scientist, but I know that fire and jet fuel aren’t a good recipe. Everyone is trying to push to the front.”

In tests, aircraft manufacturers mustshow they can evacuate a plane in 90 seconds. Real life is usually harder.

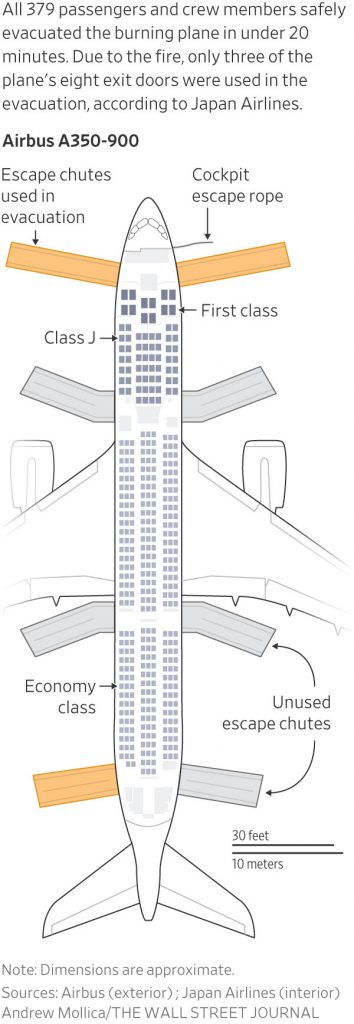

In those 18 minutes between 5:47 p.m. and 6:05 p.m. Tuesday at Tokyo’s Haneda Airport, some things went wrong. It took several minutes to get the Japan Airlines plane’s doors open. The PA system didn’t work. Most of the evacuation chutes weren’t available.

But a lot went right too. Once the doors were open, passengers calmed down and followed directions. The airline said it was prepared to stop people who tried to bring along bulky carry-on luggage—a vexing human instinct that has bedeviled previous evacuations—and wasn’t aware of anyone who did it. Although the rear of the Airbus A350 was aflame, the fire didn’t spread into the aircraft’s interior until minutes later.

Those minutes were lifesavers. The 367 passengers, as well as 12 crew, all made it to safety, with no major injuries beyond some sprains and bruises.

Japan Airlines spokesman Yasuo Numahata said of the successful evacuation, “We believe it was the result of the provision of training and knowledge brush-ups every year.”

Flight JL516 was uneventful until its landing. The nearly full plane was flying one of the world’s busiest air routes, from Sapporo in northern Japan to Tokyo. Many of the passengers were Japanese returning to the capital after visiting family over the New Year’s holiday. Some were vacationers like Hayashi and a group of Hong Kong travelers.

The airline said the pilot received permission to land from air-traffic control and repeated the permission back to the controller. Hayashi felt a tire hit the ground.

“I thought, ‘OK, smooth landing, cool.’ And then literally the next moment there was this huge collision and you hear this big boom,” he said.

The Japan Airlines jet had hit a Japan Coast Guard plane that was on the same runway, laden with food, water and other relief supplies for the region on the Sea of Japan coast that was struck by an earthquake the day before.

A transport ministry official said at a briefing Wednesday that there was no record of the coast guard plane receiving permission to enter the runway, although the control tower had authorized it to wait at a holding point near the runway about two minutes before the collision.

After the collision, the coast guard plane exploded in a fireball, killing five of the six personnel aboard. The plane’s captain was hospitalized after escaping with injuries and told investigators at the hospital that he entered the runway after receiving permission to do so, according to a coast guard official. However, the coast guard also can’t find a record of such permission, the coast guard official said.

An aerial view shows burnt Japan Airlines’ (JAL) Airbus A350 plane after a collision with a Japan Coast Guard aircraft at Haneda International Airport in Tokyo, Japan January 3, 2024, in this photo taken by Kyodo. Mandatory credit Kyodo/via REUTERS

JL516 was burning on the outside—but, crucially, not yet on the inside. It was 5:47 p.m., according to the airline. The race for survival was on.

To operate around the world, aircraft manufacturers must prove to regulators that passengers can evacuate a plane in 90 seconds. They conduct tests under conditions meant to simulate real life. A typical demonstration is conducted with people of various ages and sizes playing passengers, plus life-size dolls simulating infants. Half the exits are blocked, and blankets, pillows and bags are strewn in the aisles to create obstructions.

The tests often fall short of replicating real accident conditions, said Ed Galea, a professor at University of Greenwich in the U.K. who specializes in fire safety and analyzes evacuations. As one example, he observed that the planes in tests are level to the ground, while the Japan Airlines plane’s nose was angled down, making it harder for passengers to get to exits and use the slides.

Very few evacuations match testing conditions and can wrap up in 90 seconds, said Galea. “That’s indicative of the fact that it’s just nonsense.”

Still, the Federal Aviation Administration in the U.S. has said overall evacuation safety is high, crediting developments such as better emergency lighting and less flammable materials used in aircraft interiors.

Airlines and safety specialists have studied past evacuations to improve the chances of survival. One conclusion: The instinct of people to try to grab their bags from the overhead bin can be lethal.

The Japan Airlines plane rolled down the runway for some distance before coming to a stop. The main lights went out.

“Everyone was screaming from the initial impact and then everything got eerily quiet because everyone was confused,” Hayashi said. The passenger next to him appeared to know about emergency procedures. “She started yelling, ‘Put your head down, keep your seat belts on, stay in your seat,’ ” he said.

Hayashi estimated it took about three to five minutes for the doors to open.

Japan Airlines said it took some time to get the doors open because flight attendants first needed the pilot’s confirmation that the airplane had come to a complete stop and they needed to check whether it was safe to evacuate.

Ultimately, the airline said, only three of the eight slides were used because fire burning outside the other doors and it wouldn’t have been safe to open them. Flight attendants opened the two front doors—one each on the right and left sides of the plane—after communicating with the pilot.

An additional door in the left rear was opened by a flight attendant acting without the pilot’s authorization because a communications system breakdown made it impossible to check, the airline said.

“Passengers were yelling at the flight attendants to open the doors. It was chaotic,” said Hayashi. “It wasn’t like full-on pushing, but it was the first time I’ve seen Japanese people push each other.”

The public-address system wasn’t working, so some flight attendants used emergency megaphones or just had to shout, Japan Airlines said.

“There were some people trying to get their things, but obviously if you’re doing that, you’re holding everyone up,” Hayashi said. “People were like, ‘What are you doing? Those things don’t matter.’ ”

The doors opened at last. Japan Airlines said its flight attendants told people to leave their belongings behind and remove any sharp heels that might tear the evacuation chutes.

Officials investigate a burnt Japan Airlines (JAL) Airbus A350 plane after a collision with a Japan Coast Guard aircraft at Haneda International Airport in Tokyo, Japan January 3, 2024. REUTERS/Issei Kato/File Photo

Hayashi said he initially stayed in his seat, following the directions of his apparently well-trained seatmate. “But then the fire outside starts to pick up, and I look over at the lady,” he recalled, and suggested it might be time to deplane. She concurred.

“I got up, put my coat on and everyone starts running toward the front,” Hayashi said. He slid to safety and ran away from the plane, then watched for the next 10 minutes as those behind him followed through the front exits.

Hiroshi Kaneko, a 67-year-old philosophy professor who was returning from a visit to his mother, said he heard the flight attendants warn people not to take luggage. Kaneko, in the 10th row, picked up a small backpack containing his valuables from under the seat in front of him but left behind a large bag and slid down the front-right chute.

As Hayashi and others ran across the tarmac toward the terminal, they noticed another aircraft engulfed in flames on the runway. Not realizing they had collided with a coast guard plane, they asked each other what the other fire was but didn’t have time to investigate, he said.

By 6:05 p.m., the evacuation was complete and everyone was safe, Japan Airlines said.

Minutes later, the plane was engulfed in flames that left it a charred wreck by the next morning—the first Airbus A350 to be completely destroyed since it went into service a decade ago.

Kaneko, the professor, said the passengers around him didn’t panic and he was more scared when he got home and saw the footage on television. In retrospect, he said, the door delay made sense. “It takes time to make sure doors are safe, and it is dangerous to open a door with a flame,” he said.

While the evacuation was happening, Hayashi said, “it’s just smoky and you don’t know what’s going on.” Back at the terminal, “we found out that five people on the other plane died. When we were in the waiting room of the airport, the eeriness began to set in.”

There, Hayashi took stock while eating a salmon-filled rice ball known as an onigiri that was handed out by staff. He was without his keys and would have to stay with a friend. He lost a suitcase full of clothes, including two favorite sweatpants, as well as his laptop and his GoPro. All were replaceable. At that moment, none of them meant anything.

“It was the best onigiri I’ve ever had in my life,” Hayashi said.

—Miho Inada contributed to this article.

Write to River Davis at river.davis@wsj.com, Megumi Fujikawa at megumi.fujikawa@wsj.com and Alison Sider at alison.sider@wsj.com