Fleeing from communist to capitalist countries was common practice during the Cold War. In today’s sports, socialism might become the more popular choice—it is just good business.

Earlier this month, the top European Union court ruled in favor of former French soccer midfielder Lassana Diarra in arguing that some of the sport’s transfer rules break EU law. This is a landmark judgment and comes only months after the court gave wings to a breakaway SuperLeague , a U.S.-style closed tournament that was proposed by 12 of the Continent’s top clubs in 2021.

Though the end result remains uncertain, it might be yet another factor bringing Europe closer to the American way of doing sports .

The irony here, given the U.S.’s self-proclaimed ethos of economic laissez-faire, is that its elite competitions, such as the National Football League and the National Basketball Association, have strong mechanisms to rebalance the stakes in favor of the worst performers. In Europe, the cradle of the welfare state, clubs have been mostly unconstrained.

It harks back to the grassroots emergence of soccer in 19th-century Britain. Teams formed tournaments because they needed a unified set of rules. The most successful ones were overrun by applicants, which led to the establishment of promotion and relegation systems that were replicated across Europe. Clubs had strong political, industrial and class-based links with local communities, some of which give them distinct identities to this day, such as Tottenham Hotspur’s link to the London Jewish community, FC Barcelona’s backing of Catalan nationalism and Steaua Bucharest’s military origins.

By contrast, modern American sports were top-down commercial endeavors from very early on. In 1876, the National League of Professional Baseball Clubs pioneered the for-profit, closed league granting teams exclusive rights to operate in a city or region. Franchisees invest big money with the knowledge that their team won’t get relegated, but are usually forced to split revenues from national broadcast deals equally, and often operate under some form of salary cap that benefits the weaker teams. In the NFL, players get a fixed share—roughly 48%—of the league’s revenue through a collective-bargaining agreement.

Draft systems give the worst teams first pick of promising college or high-school players. Stars can later switch clubs, but usually do so as free agents or as part of a trade for another player.

In Europe, by contrast, clubs bring youngsters up and hold players under contract until a rival pays a transfer fee. This leads the rich to hog all the talent, be it by buying it like Real Madrid or by generating it at their academy like Barcelona.

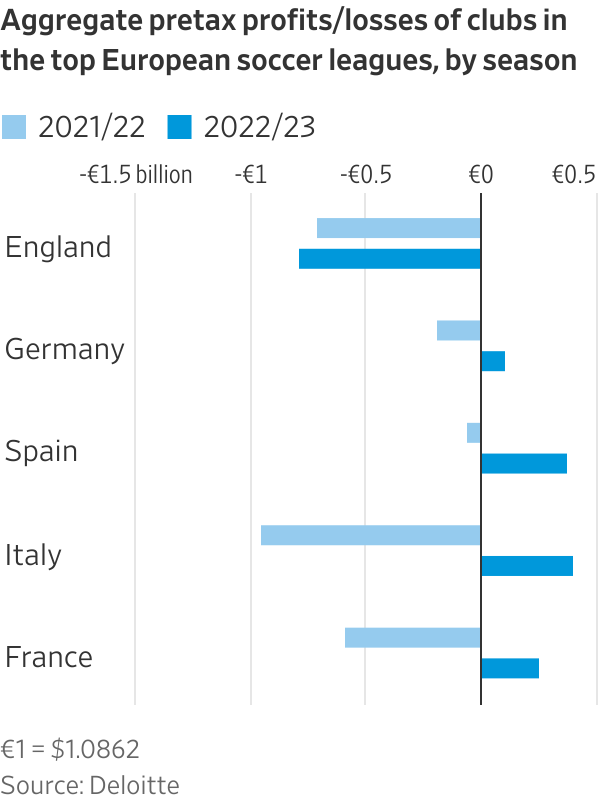

Yet European clubs often operate at a loss. In an industry of superperformers, that laissez-faire approach leads to a kind of Marxist paradise: Labor has all the power over capital, and windfalls end up in the pockets of stars and intermediaries. Research, including a 2020 paper by economists Luis Carlos Sánchez, Ángel Barajas and Patricio Sanchez-Fernandez, finds that financial performance in soccer comes at the expense of sporting success.

Revenues are also lower. Soccer generates $41 billion a year, Deloitte estimates, which is only twice as much as the NFL despite having eight times as many fans. This figure also accounts for all global competitions: Clubs in the English Premier League, for example, generate less than $8 billion.

It certainly isn’t a branding issue: Madrid and Manchester City generate sponsorship, merchandising and licensing revenues of between $350 million and $450 million a year, which is in the ballpark of what is raked in by the Dallas Cowboys, the most valuable NFL team. A stronger identity and more “one-club men” raised at the academy are actually marketing assets.

The big gap is in media rights. Broadcasting the NFL and the NBA is worth about $12 billion and $7 billion a year, respectively, compared with about $2 billion each for the Premier League and the UEFA Champions League, according to Ampere Analysis.

The revamped Champions League format that kicked off last month underscores why: Despite attempting to tweak the format to feature more attractive head-to-heads, most matches are in the vein of Bayern Munich’s recent 9-2 thumping of Dinamo Zagreb. Financial resources are too unbalanced.

“In Europe, everyone’s priority is to win matches—there is no understanding that we are selling a unified product,” said Xavi Puyada, chief financial officer of the EuroLeague, the Continent’s top club basketball competition.

Its 18 teams together gross around $540 million a year, compared with $11 billion for the NBA, and most of them post steep losses. This is why, last month, the EuroLeague became the first elite European competition to announce the introduction of enforced salary bands, defined as a percentage of participants’ average revenues, and agreed upon by the players’ union.

Puyada aims to rein in the power of stars and create a more attractive, balanced competition. His inspirations are the NBA’s “soft” salary cap, which penalizes transgressors with a “luxury tax” and gives the proceeds to the rest, as well as Major League Soccer’s carving out of exceptions. In this case, they will apply, among others, to a team’s top-two stars and “extended-tenure” players.

Meanwhile, the many American investors who have scooped up clubs across the Atlantic—including RedBird Capital Partners, Clearlake Capital and, more recently, Inter Milan’s Oaktree Capital Management—are running them in a way more akin to U.S. franchises. They fixate on profit, debt management, revenue generation and data-driven analyses of the game, even if they aren’t always successful at it.

In recent years, European soccer has started enforcing “financial fair play,” which in a roundabout way also edges closer to U.S. sports. Stricter application of these rules allowed Spain’s LaLiga to eke out a profit last season. Still, they often limit spending by small teams more, while failing to restrain clubs backed by profit-insensitive billionaires, often from petrostates, such as Manchester City and Paris Saint-Germain.

SuperLeague organizers claim it could kick off next year, but that looks doubtful given strong opposition by officials and many fans. Change is difficult.

Nevertheless, investors will keep pushing to stop leaving money on the table. Also, the Diarra case raises the risk that players could start successfully tearing up their contracts. Transfer fees could plummet, torpedoing the main source of income for medium-size clubs and giving stars even more power to squeeze big wages out of the richest teams. If so, a larger rethink might be unavoidable.

In the case of sports, the Marxist claim about the contradictions of the capitalist system might have a point.

Write to Jon Sindreu at jon.sindreu@wsj.com