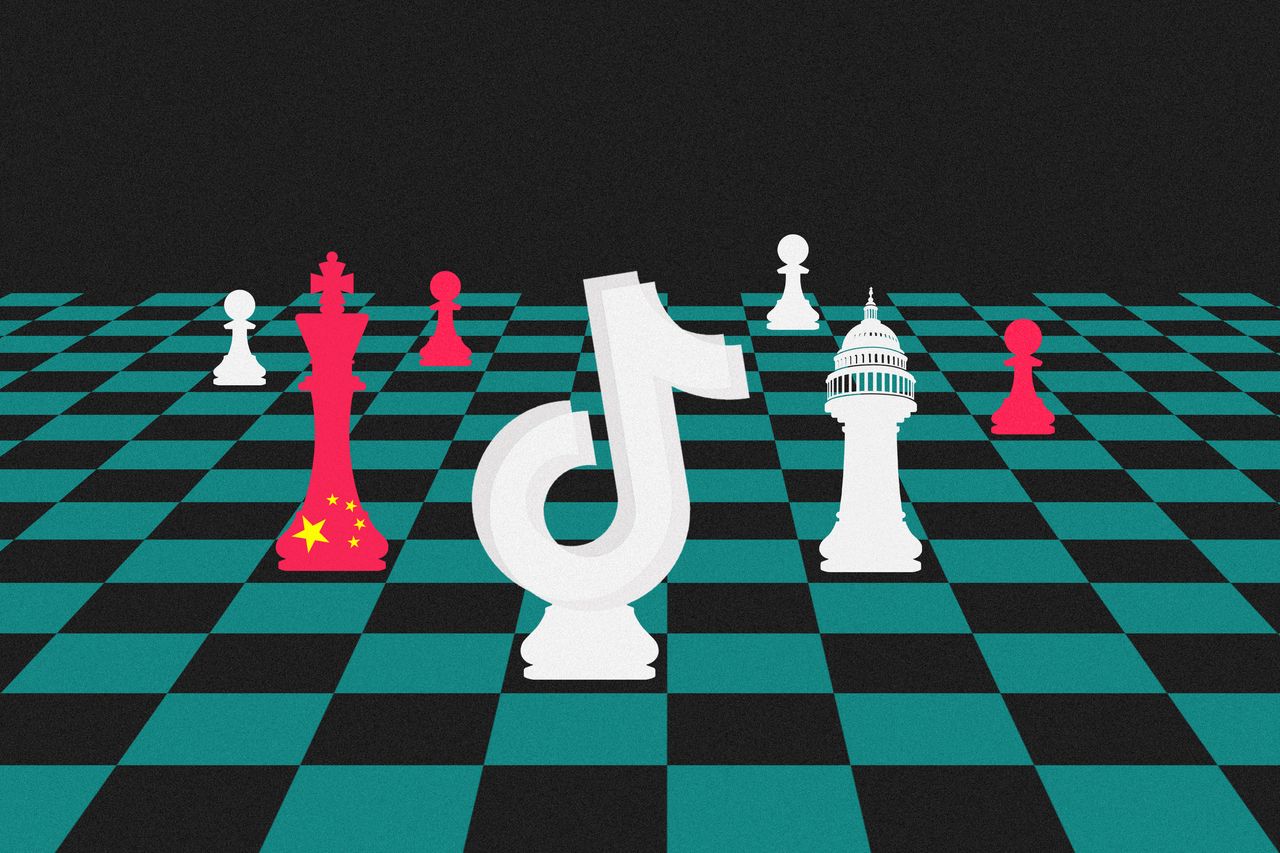

TikTok spent the past four years trying to fend off a U.S. ban, but it never figured out Washington.

The law signed by President Biden on Wednesday requiring a sale or ban of the popular app was in part the product of tectonic shifts in U.S.-China relations and coordinated, stealthy efforts by its critics on Capitol Hill.

Those factors were compounded by a series of miscalculations that, in the end, left the Chinese-backed company scrambling for support among its users in ways that were ineffective or even backfired.

TikTok now faces a battle for survival in the U.S. courts. Its other alternative is to find a deal that could extract some value out of its U.S. operation—but faces opposition from Beijing and uncertain interest from U.S. buyers. Failure on those fronts likely would mean the end of a U.S. business that forms the core of TikTok’s global operations, a grievous wound for the most internationally successful internet app to have come out of China.

This account is based on interviews with current and former employees of TikTok as well as lawmakers, and others involved in the battle over the app.

Missed opportunities

They say TikTok Chief Executive Shou Zi Chew missed opportunities early in his tenure to try to build support on Capitol Hill—and instead depended on negotiations with U.S. security officials over a complex restructuring that never panned out.

In recent months, TikTok was outflanked by opponents and repeatedly surprised by the surging momentum against it in Washington, leading to last-ditch steps to rally support that reinforced many lawmakers’ concerns about the Chinese app’s ability to influence public opinion.

“I don’t think they ever understood how concerned we were with the national security implications of so much American data being put at risk,” House Majority Leader Steve Scalise (R., La.) said of TikTok.

It is unknowable whether different strategies could have changed TikTok’s fate, given Washington’s deepening, bipartisan distrust of China, especially on tech matters.

“The government was not negotiating in good faith, and they intentionally misled Congress about the facts,” said Michael Beckerman , TikTok’s vice president of government relations. “There is not a CEO in the world that could have done a better job than Shou.”

During its 2020 battle against a ban effort by President Donald Trump , TikTok had been led by a U.S. executive and an Australian. In mid-2021, parent company ByteDance tapped Chew, in part because of his extensive bicultural experience . Born and raised in Singapore, the 41-year-old is fluent in Mandarin, attended Harvard Business School and worked for Goldman Sachs.

Need to build trust

He lacked, however, extensive experience with U.S. politics. People close to Chew urged him to get to know Washington’s power players. While Chew spoke about the need for TikTok to build trust, he didn’t give priority to such meetings, instead focusing on revenue, product features and a potential IPO.

Chew left government relations to his general counsel, Erich Andersen , a longtime Microsoft executive who had served as head of the U.S. tech giant’s intellectual property group.

Andersen spent much of 2022 negotiating with the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S., a federal panel known as Cfius, over TikTok’s proposal to wall off U.S. user data. Called Project Texas , the proposal was designed to assuage concerns that Beijing could pressure TikTok to provide data or influence Americans’ views—demands TikTok has said it would never comply with.

Chew was getting conflicting advice. Some TikTok executives argued that he shouldn’t meet with lawmakers because the Cfius talks were confidential. Others said TikTok’s problems were fundamentally political and he could engage without detailing the negotiations.

In early 2022, Chew told employees in multiple calls that a deal with the U.S. government was nearly done. But within a couple months, it was clear that something was off. By August, Cfius wasn’t returning TikTok’s calls.

Visits to lawmakers’ offices

That December, TikTok learned House lawmakers wanted Chew to testify. Twenty months into his tenure, he made his first big Washington tour, spending much of January through March visiting the offices of more than two-thirds of the approximately 50 members of the House Energy and Commerce Committee.

A TikTok spokeswoman said Chew had previously met with some lawmakers, and attended a congressional sporting event, in 2022.

Chew faced a barrage of harsh questioning over more than five hours in the March hearing. Chew’s team felt much of the grilling was unfair, with lawmakers suggesting incorrectly that he is a Chinese citizen and his boss is China’s Communist Party leader.

But executives felt they had gained ground with users. One measure: Chew’s TikTok account soared from fewer than 15,000 followers before the hearing to more than three million soon after.

TikTok was getting help from Club for Growth, a powerful conservative group backed by financier Jeff Yass, whose Susquehanna International Group is a major shareholder of TikTok’s parent company. And President Biden joined TikTok on Super Bowl Sunday to reach younger voters.

The situation lulled some inside TikTok into thinking it was safe. But the ground was already shifting against it.

Drafting bipartisan legislation

After Chew’s testimony, Scalise began discussions with lawmakers, tasking a new select committee on China with drafting bipartisan legislation.

That small team worked during the fall of 2023, fueled by a steady stream of pizzas, and the bones of the agreement were in place by late 2023. The team quietly worked with the Justice Department to make sure the bill was drafted with the best shot of staving off a legal challenge.

Keeping the drafting under wraps helped delay the deluge of TikTok lobbying, which previously had some success deterring legislative efforts.

Sentiment against China in Congress was continuing to sour, and criticism of TikTok gained new momentum because of anger over TikTok videos about the Israel-Hamas conflict, which many critics claimed were disproportionately anti-Israel. TikTok says it doesn’t promote either side of an issue.

Concerns about social media

TikTok also was among the companies in the crosshairs over broad concerns about social media.

“TikTok is facing resistance from all the critics of big tech, all the criticism of social media, they’re facing all the criticism of Chinese apps, of China-based tech companies,” said Daniel Castro, vice president at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a Washington-based research group funded by U.S. tech giants and other companies.

When plans for a vote on the proposed House bill emerged in early March, TikTok executives were blindsided .

In response, the app served users a notification urging them to call lawmakers to protest a possible ban. The stunt backfired, showing TikTok’s powerful ability to mobilize users for a political goal, lawmakers and congressional aides said.

Meanwhile, Kellyanne Conway, a former senior White House official, made calls on behalf of the Yass-backed Club for Growth, urging lawmakers to reject the legislation as a violation of free speech and an unfair boost to Facebook , according to people familiar with the discussions.

Pressure on Republican lawmakers

Republican lawmakers also received calls from Doug Stafford, one of the people said. Stafford is an adviser to Sen. Rand Paul (R., Ky.), who according to federal records has received more than $24 million in political donations from Yass and Yass’s wife since 2015.

TikTok’s offices in Los Angeles. PHOTO: JESSICA PONS FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The people familiar with the calls said they understood the message from Conway and Stafford to be that politicians wouldn’t get funding from Yass-backed groups in the future if they voted for the bill.

A spokesman for Yass, a longtime supporter of libertarian causes, said opposing a TikTok ban was “libertarianism 101.” In a statement, Club for Growth President David McIntosh said Yass has never directed the organization to take a position on any issue, and that how lawmakers voted on the TikTok bill wouldn’t affect whether Club for Growth supports them.

The pressure stoked some anxiety among lawmakers but also some resentment. One lawmaker, in response, helped assemble a 278-page packet to other Congress members that made the case for the bill. It laid out arguments about national security concerns with TikTok.

The House Energy and Commerce Committee approved the bill unanimously, and it sailed through the House in a 352-65 vote. Scalise said he hosted a celebration just off the House floor right after the vote. Some House staffers played “TiK ToK,” the 2009 hit song by Kesha.

Trying to leverage support

The company stuck with its strategy of trying to leverage support among U.S. users and creators—though that again demonstrated the ability to influence opinion that critics had feared.

The company decided to post a video to its main account that featured Chew encouraging users to lobby their senators. The video went viral almost instantly, indicating that the company had used a tactic called “heating” to promote the video widely on the platform, according to people familiar with the process. The video ultimately received more than 37 million views.

The spokeswoman said TikTok didn’t heat the video.

The TikTok bill looked like it had stalled after arriving in the Senate. Executives again took solace, assessing that it might drag out until after the presidential election.

Once again, TikTok’s assessment proved too optimistic.

Behind the scenes, the bill’s supporters in the House were searching for a must-pass bill to attach it to. They found it in a Senate-backed $95 billion package of foreign aid to Ukraine and Israel. The package passed the House last weekend, followed by the Senate late Tuesday .

Ultimately, the bill passed through Congress—which hasn’t been able to agree on other tech legislation—because TikTok couldn’t dissuade lawmakers that its ownership is a threat to the U.S.

“The divestiture bill is a national security bill,” said Sen. Brian Schatz (D., Hawaii), a member of the Commerce Committee. “Whatever we think about social-media companies—that’s for another day.”

Chew once again sought support from users in a defiant message on TikTok. “It’s obviously a disappointing moment, but it does not need to be a defining one,” he said. “Rest assured, we aren’t going anywhere.

Write to Georgia Wells at georgia.wells@wsj.com and Kristina Peterson at kristina.peterson@wsj.com