The U.S. is experiencing its largest immigration wave in generations, driven by millions of people from around the world seeking personal safety and economic opportunity. Immigrants are swelling the population and changing the makeup of the U.S. labor force in ways that are likely to reverberate through the economy for decades.

Since the end of 2020, more than nine million people have migrated to the U.S., after subtracting those who have left, coming both legally and illegally, according to estimates and projections from the Congressional Budget Office. That’s nearly as many as the number that came in the previous decade. Immigration has lifted U.S. population growth to almost 1.2% a year, the highest since the early 1990s. Without it, the U.S. population would be growing 0.2% a year because of declining birthrates and would begin shrinking around 2040, the CBO projects.

The surge in immigration has been controversial, because most migrants didn’t come through regular legal channels. Less than 30%, or 2.6 million, are what the CBO counts as “lawful permanent residents,” which includes green-card holders and other immigrants who came through legal channels, such as family or employment-based visas. In addition, the CBO estimates the nonimmigrant foreign population, which includes temporary workers and students, has grown by about 230,000 since the end of 2020.

The CBO refers to most of the other 6.5 million as “other foreign nationals.” The bulk of that group crossed the southern border without prior authorization, turned themselves over to American border officials and requested asylum. They were assigned court dates, sometimes years in the future. While the newcomers wait, some in government-provided shelters at first, most of them work.

There’s much that we don’t know with precision about this population. Immigration court data is incomplete because it only covers migrants suspected of breaking immigration and other laws. Meanwhile, the House of Representatives’ Homeland Security Committee estimates at least two million have slipped through the border undetected since late 2020. The CBO’s figures are a combination of estimates and projections. Some sources estimate lower numbers of immigrant arrivals.

But information does trickle in, via a monthly Census Bureau survey of 60,000 households and the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a database of immigration-court filings curated by Syracuse University. They paint a picture of an overwhelmingly Spanish-speaking cohort that is younger, less-educated, and more available to work than the native U.S. population.

The number of post-2020 immigrants who participate in the monthly Census survey is small and demographers believe unauthorized immigrants are less likely to respond when the government calls to ask questions.

But looking at the people who do respond to the monthly Census allows some inferences about their characteristics. The Journal looked at the average from May through July.

Recent migrants are younger and more likely to be of working age than U.S.-born Americans. Of foreigners who arrived since 2020, 78% are between the ages of 16 and 64, compared with 60% of those born in the U.S., according to the monthly census data.

That helps explain why they are also more likely to be in the labor force. Of recent immigrants age 16 or older, 68%—the participation rate—are either working or looking for a job, compared with 62% for U.S.-born Americans. In raw numbers, that likely amounts to more than five million people, equal to roughly 3% of the labor force.

Recent immigrants’ participation rate is likely to climb further in coming years. It often takes more than six months for someone who has entered the U.S. to receive a work permit. Labor-force participation for foreigners who arrived from 2004 through 2019 is a lofty 73%, according to census data.

And while 5% of working-age Americans are unable to work—often because of chronic illness, disability, drug addiction or the need to care for family members—less than 1% of post-2020 immigrants report being unable to work.

The 12 largest source countries for newcomers assigned immigration-court hearings since late 2020 are in Latin America or the Caribbean, the TRAC data show, led by Venezuela at 14%, Mexico at 13% and Honduras at 8.5%.

Monthly census data paint a slightly different picture, suggesting that Mexico is the most-common country of origin, followed by Venezuela and India.

The newcomers are settling around the country. For the 4.2 million people who have been assigned hearings in immigration court since late 2020, the top-five destination states are Florida, Texas, California, New York and New Jersey.

The states that have received the fewest of these immigrants: Alaska, Vermont and West Virginia.

But while most recent immigrants are able to work, many aren’t ready for high-skilled jobs: The census data show immigrants who arrived since the start of 2020 are more than twice as likely to lack a high-school diploma as U.S.-born workers.

Perhaps counterintuitively, recent immigrants are also slightly more likely to hold a bachelor’s degree or higher than the U.S. born. The data don’t make it clear why.

According to immigration-court data, about 80% of recent immigrants’ spoken language is Spanish. A survey last year by KFF and the Los Angeles Times found that around half of overall U.S. immigrants say they speak English “very well” or exclusively.

Immigrants who have arrived since the start of 2020 face higher jobless rates than the broader population. Unemployment for recent immigrants averaged 8.2% between May and July, versus 4.2% for American-born workers and 3.5% for earlier immigrant cohorts. Overall unemployment has crept up this year, to 4.3% in July, in part due to the swelling numbers of immigrants looking for jobs.

Recent immigrants tend to earn less than U.S.-born workers because of their lower level of education, lack of English, and in some cases because they are working without permission. They might also compete with existing workers with less education and put downward pressure on their wages, too. Through these channels, the surge in immigration could weigh slightly on overall wages and productivity in the near term, according to the CBO.

However, the drag fades over time as migrants gain experience, and those with college degrees contribute to innovation, the CBO says. And from the day they start working, migrants pay federal taxes, helping to reduce the federal deficit.

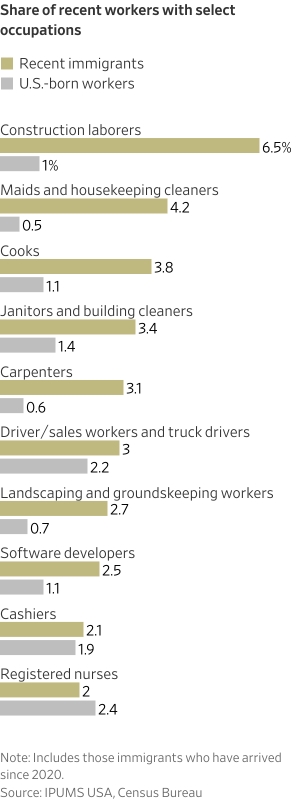

An outsize share of post-2020 immigrants are working in low-paying jobs. The most-common occupations, according to the census data: construction laborers, maids and housecleaners, and cooks. Such jobs are more likely to be held by immigrants, especially those who arrived recently, than by American-born workers.

Many migrants do fill skilled jobs; the eighth most common occupation of all post-2020 migrants is software developer.

Write to Paul Kiernan at paul.kiernan@wsj.com , Danny Dougherty at danny.dougherty@wsj.com and Peter Santilli at peter.santilli@wsj.com