I was giving a book talk recently at a lovely cheese and food shop in Hudson, N.Y. called Talbott & Arding, and the owners sent me away with some of their house-made crackers as a gift. I immediately became hooked on their rye and caraway crackers made from grains sourced from the Hudson Valley. They are as thin as parchment, and the flavor is grainy, salty and heavy on the caraway—like the rye bread of dreams. Wondering how I could get some more, I found that on the Talbott & Arding website, these delicious crackers cost $11 for five ounces. Worth every cent, if you can afford it.

How did crackers become so fancy? For most of the 20th century, crackers in America were defined by their cheapness. The only thing that was ritzy about Ritz crackers—the round, slightly greasy yellow crackers that were first sold in 1934 for 19 cents a pack—was the name.

The original crackers were a survival food. In the ancient Middle East, people baked small hard flatbreads as a way to have something to eat while on the move, especially in the military. Roman soldiers were supplied with a kind of hard biscuit called bucellatum designed mainly for withstanding extreme weather conditions. They sound similar to the hardtack eaten by Civil War soldiers—a plain, tough, flour-and-water biscuit that was best when crumbled in soups. Hardtack by itself seems to have been almost impossible to chew. There’s a clue in the name.

I have never eaten military rations, but I can’t help feeling that the spirit of hardtack found its way into some of the early commercial cracker recipes. Growing up in Britain, I remember crackers as dry, dull things, although they tasted OK if you had enough cheese to go with them. My Granny practically lived off Jacob’s Cream Crackers, a square, bland cracker much loved in England, which she ate with brie or cheese spread from a tube. Sometimes she splashed out and bought something called Water Biscuits instead—equally dry but slightly more flavorful, because they were baked longer.

There were also various low-fat crackers aimed at dieters. The most popular was Ryvita Rye Crispbread, which had a punishingly hard and fibrous texture and many holes. As a child, I figured out that the only way to make a Ryvita edible was to butter it so heavily that the butter lodged in every hole. This may have slightly undermined the plan of using these crackers to help with weight loss.

In the U.S., too, crackers were originally plain food for the masses. The word “cracker” first appeared in print in America in 1739 and gradually replaced the older “wafer.” The leading cracker of the 19th century was the soda cracker, leavened with bicarbonate of soda. There were also Common Crackers, a puffed and hollow cracker that was sometimes split and eaten with good cheddar cheese. Crackers were sold in every American grocery store in giant barrels, and people would gather around that cracker barrel to share the town gossip. The downside was that whoever bought the crackers from the bottom of the barrel might be greeted with soggy crackers and rodent droppings.

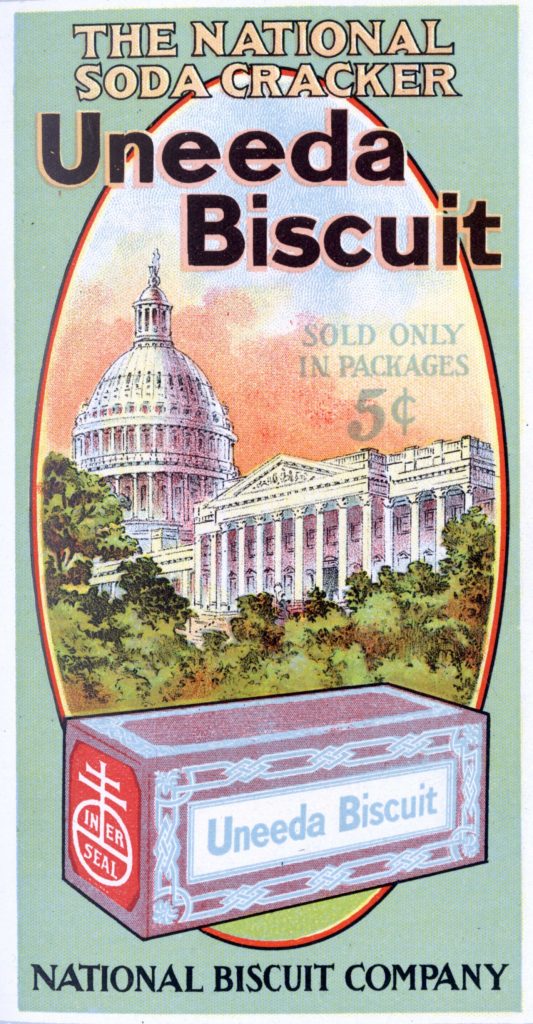

Advertisement for Uneeda Biscuit features an illustration of the US Capitol building and a box of crackers, 1912. It originally appeared in Herbert Cecil Duce’s ‘Poster Advertising’ (published by Blakely Printing). (Photo by Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images)

Crackers only became a packaged product with the launch of the Uneeda Biscuit by the National Biscuit Company (Nabisco) in 1898. When I first saw the name Uneeda on the page, I couldn’t understand it. Then I said it out loud and got it. Uneeda Biscuits were essentially just the same old boring soda crackers, yet by 1900 Americans were buying 10 million packages a month. Uneeda’s great selling point, dreamed up by an ambitious lawyer called A.W. Green, was that they came in individual packages designed to keep the crackers fresh and the rodent droppings out.

The success of Uneeda led to other packaged Nabisco crackers, notably the Ritz in 1934, which claimed to offer Depression-era customers “a bite of the good life.” Crackers soon became something that almost every American expected to have in their pantry, whether Goldfish crackers for children or saltines to go with a drink.

But now we are in the era of the genuinely ritzy cracker, at least for some. Thanks to new tools and technologies, many high-end restaurants will start the meal with extraordinary-looking puffed-up crackers, sometimes made from tapioca, dyed black with squid ink or purple with beet. One of the first chefs to serve these gourmet puffed crackers was Daniel Patterson at Coi in San Francisco. In 2007, one of Patterson’s chefs figured out that by taking some brown rice, overcooking it, drying it and then frying it in insanely hot oil, he could produce a totally new kind of rice cracker with a papadum-like lightness, which could be seasoned with seaweed and chili flakes. These are not the kind of cracker you’d find in any barrel.

Swanky crackers aren’t limited to restaurants. Think of a grain, any grain, and someone will have made a fancy cracker from it and sold it for a premium with an elegant label. Crackers for cheese have become far more varied and delicate than in the past, as the Talbott & Arding example shows. You can buy tiny rectangular toasts flavored with cherries or hexagons blackened with charcoal.

If you love the flavor of luxury crackers but not the price tag, do consider making them yourself. They are one of those things that sound tricky but are actually easier than boiling eggs. Google “Ottolenghi chickpea cracker” for an excellent starting point. You make the gluten-free mix in a bowl and bake it to a giant golden crisp on a parchment-lined tray, no rolling pin required. Season it with any seed or spice your heart desires (I favor cumin seeds).

For those who don’t enjoy baking, almost zero-effort crackers can be made from very thin slices of stale bread, coated with a mixture of honey, sesame seeds and olive oil and baked until golden. The full recipe for these “wafer toasts” is in an excellent new cookbook by young British food writer Kitty Coles, “Make More With Less.” They taste so good, you may entertain ideas of going into the fancy cracker business yourself.