Back in June, when China’s youth unemployment rate hit a record 21.3%, Western analysts saw it as a sign of a moribund recovery. China’s ministry of statistics responded by announcing it would no longer publish the statistic.

Six months on, that move might have had the desired effect. One out of every five young people without a job would typically be considered a crisis. But in the absence of data, the state of China’s youth labor market has become a matter of anecdote and guesswork, which is likely how Beijing wants it.

“They rig their numbers and, when their numbers get embarrassing, they stop producing them,” said Derek Scissors, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute who studies China’s economy. “They will get away with it. After a while you’ll have nothing to discuss.”

The anecdotes and private data we do have show something is still amiss.

The polling firm Morning Consult runs a daily consumer sentiment tracking survey in China that shows younger people have consistently lower sentiment than older groups, underlining how much more unsatisfied, economically, the youth remain. (In the U.S., by contrast, young people tend to have better sentiment than older cohorts.)

Anecdotally, there is a “lying flat” movement, where disenchanted young people opt out of the job market entirely. David Bandurski of the China Media Project, which studies the Chinese media landscape, traces the phrase to a viral social-media post from an unemployed youth titled “lying flat is justice,” which inspired an entire movement “to opt out of the struggle for workplace success, and to reject the promise of consumer fulfillment.”

It has clearly appealed to some Chinese youth on social media. But how prevalent is it really? No one knows.

Anecdotally, there has also been the rise of “full-time adult children”—half trend story, half social-media joke—about jobless adults who live with their parents in exchange for an allowance.

One estimate in China from data through March (before the youth unemployment statistics were halted) put the number of such full-time adult children at 16 million young people. (The total population ages 16 to 24 is around 150 million.)

But even if this figure were regularly updated, it isn’t really the same as unemployment, which is defined as actively seeking employment, and can only be determined with a properly designed and executed survey. Not everyone who lives at home does so because they’re unemployed or have given up looking for work. Others might be taking care of aging parents, preparing to resume studies, or sick.

Chinese state media has adopted the term “slow employment” for taking off time after college. You know, hanging out. Doing a bit of travel. A Chinese human-resources agency put out a survey saying about 19% of graduates will choose “slow employment” this year, up from 16% last year.

Some probably have genuinely chosen to launch their careers slowly but for others, this is a face-saving euphemism for unemployment. Once again, this doesn’t really tell us much about the true state of unemployment.

The stories sound not unlike those in the U.S. such as the (viral on social media) “quiet quitting,” which refers to not taking your job too seriously, to showing up but quietly doing the bare minimum. It’s a little funny. People certainly talked about it a lot. Some people certainly slack off or conclude they’ve given their employer enough.

In the absence of data, such anecdotes proliferate. They’re amusing. They certainly hint that something is a bit off. But they are poorly defined—certainly less well defined than, say, unemployment—and provide little sense of what’s changing from one month to the next.

Meanwhile, obtaining reliable data from China is getting harder. Earlier this year, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, the largest academic database of government reports, restricted access to universities outside China. Shanghai-based Wind Information, a provider of economic and financial data, stopped foreign think tanks and research firms from renewing their subscriptions.

China’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security used to publish a quarterly look at job openings (akin to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) before quietly ending the report in 2021.

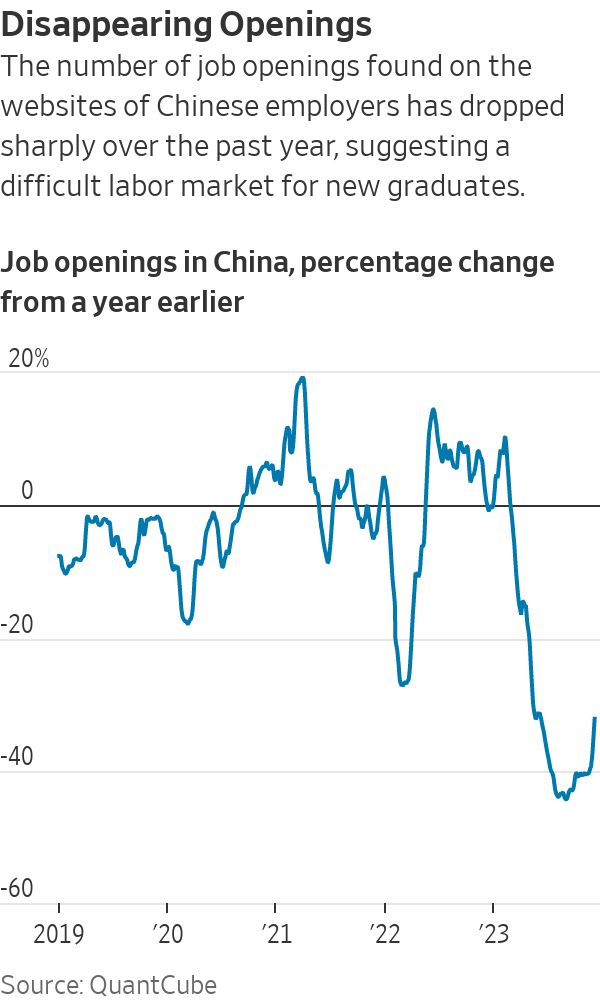

QuantCube Technology, which has developed a range of alternative measures of China’s economy such as satellite-tracked urban pollution, tracks online job listings from Chinese employers. It had a fairly strong 75% correlation with the official job-openings figure until its publication ceased, the Paris-based firm said.

QuantCube’s measure of job openings began to plunge in May, and as of early December was 35% lower than a year earlier—not a great sign in an economy desperately trying to absorb huge numbers of jobless youth.

These data points and anecdotes all tell part of a troubling story about the economy. But without a proper statistic, they don’t directly answer the question that China doesn’t want asked: How high is youth unemployment? In other words, hiding the data is working.

Write to Josh Zumbrun at josh.zumbrun@wsj.com