When Alex Zhu, a native of China’s Shandong province, studied in Europe in 2017, she had many fights with her classmates about the Dalai Lama.

Her best friend, a Danish student, admired the exiled spiritual leader of Tibet as a symbol of peace. Zhu considered him an extremist working to wrest Tibet from China. She thought her friends were brainwashed; they were amused by her venom against the Buddhist spiritual leader.

Zhu, now in her early 30s, was one of many outspoken Chinese students around the world who were quick to defend China. Chinese leader Xi Jinping ’s talk of a “China Dream,” what he has called “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation,” helped fuel nationalistic fervor among young Chinese. Groups of Chinese students in the U.S. made headlines as they defended Beijing’s human-rights record or denounced Hong Kong pro-democracy protesters .

A protester’s umbrella catches on fire during clashes with police outside Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU) in Hong Kong, China November 17, 2019. REUTERS/Adnan Abidi TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY

They became known as “little pinks.” Zhu is one of many who have since made a 180-degree turn, becoming fierce critics of the Communist Party. The pandemic was a turning point for many Chinese, who grew increasingly angry over Beijing’s heavy-handed Covid-19 restrictions and suppression of information.

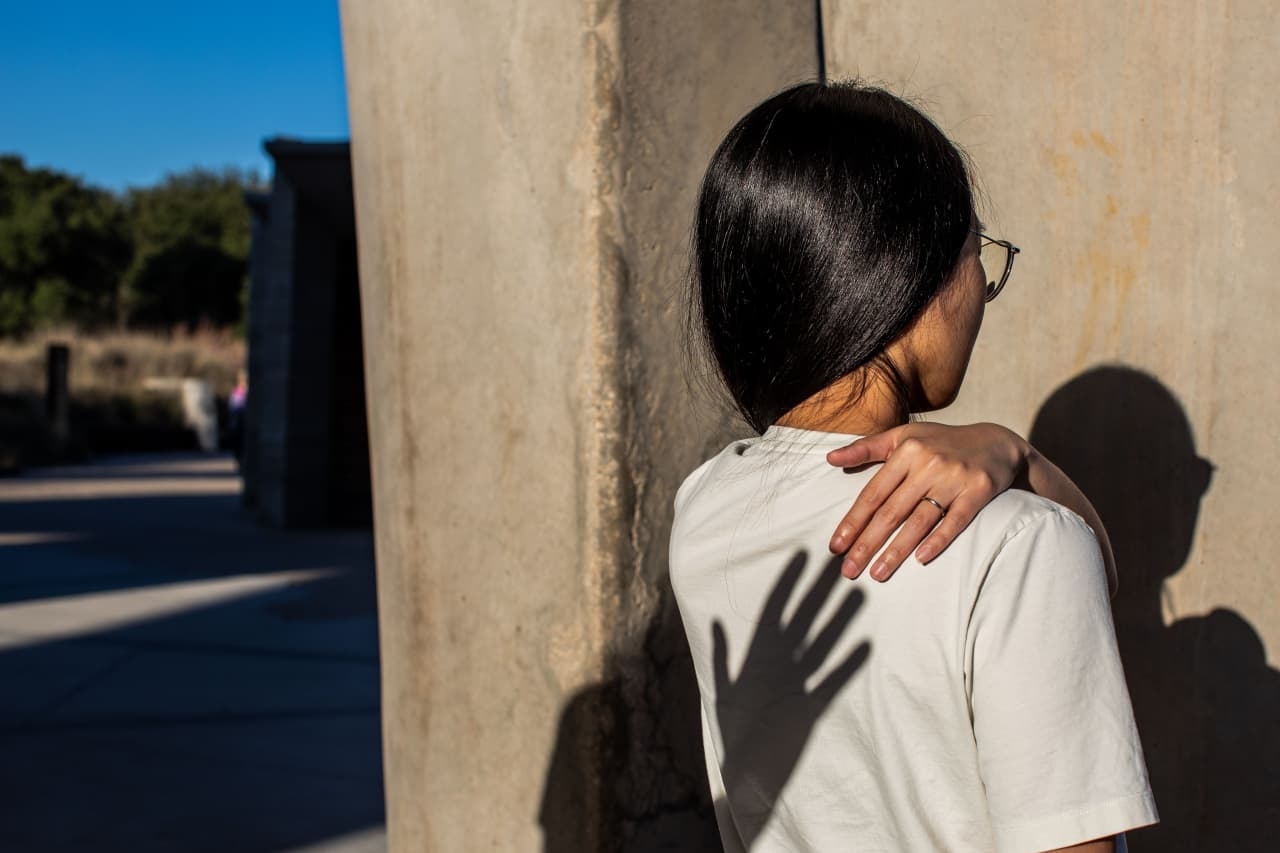

Even though she lives abroad, she preferred using her English first name for this article for fear of repercussions should she return to China.

Zhu describes herself as a little pink when she arrived in Europe with an undergraduate degree from a Chinese university and immense pride in her home country. She grew up during China’s economic boom and a wave of patriotic education in schools to prevent a repeat of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests .

In Europe, all that she had believed came into question—especially after she fell in love with an American.

At the time, the West started accusing Chinese authorities of a mass detention of Uyghurs in China’s far-western Xinjiang region, part of its forced-assimilation campaign of mostly Muslim minorities. Beijing denied the allegations, describing the camps as vocational training centers to “deradicalize” people suspected of extremism. Zhu and her boyfriend argued about it constantly. He printed out articles about the camps; she refused to read each one.

“I thought that just glancing at them meant I would be brainwashed by Western capitalism,” Zhu said.

Within months, the couple was on the verge of a breakup. “I loved this person so much I started doing my own research,” she said. Reading accounts by Uyghurs online and in Western media, she was shaken: “One Uyghur in exile might be telling a lie, but when 100 or more people come forward to share their stories, you just start to believe it is credible.”

The arguments continued after Zhu moved back to China with her boyfriend in tow. In 2019, when they were living in Shanghai, the relationship came close to collapse over the pro-democracy protests taking place in Hong Kong.

Zhu, who was reading the nationalist Chinese tabloid Global Times, published by the Communist Party’s People’s Daily, saw the protesters as rioters attacking police and residents. Her boyfriend, by contrast, was moved by the energy of the protests. She thought he was crazy, asking, “How can you support such violence?”

Anti-government protesters stand in a cloud of tear gas unleashed during a stand off with riot police at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, in Hong Kong, China November 12, 2019. Reuters has been awarded the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in Breaking News Photography for Hong Kong protests. REUTERS/Tyrone Siu

In July 2019, the couple took a trip to Hong Kong. Zhu avoided the protests but was exposed to pepper spray while waiting for her cheung fun rice noodle rolls at a food stand. As she started coughing and tearing up, a team of demonstrators carrying first-aid kits arrived, offering eye drops and helping to regulate the breathing of those sprayed.

“I felt an electric current in the air, making me feel both tense and a bit excited,” Zhu said. Hong Kongers’ grievances started to make sense to her. “My suspicion was cast aside by tear gas,” she said.

An anti-extradition bill protester is detained by riot police during skirmishes between the police and protesters outside Mong Kok police station, in Hong Kong, China, September 2, 2019. REUTERS/Tyrone Siu/File photo SEARCH “PULITZER REUTERS” FOR THIS STORY. SEARCH “WIDER IMAGE” FOR ALL STORIES.

When the pandemic hit, Zhu, like many Chinese, was upset to learn how authorities in Wuhan, the epicenter of Covid, covered up early signs of the virus. Like others, she grieved the death of Li Wenliang, a doctor who had been interrogated by authorities after he issued early warnings about the virus , and then succumbed to it.

Zhu started seeing a surge of social-media posts from desperate Wuhan residents seeking help. Then the posts vanished. She began taking screenshots of everything that might be prone to censorship, even creating a Telegram channel broadcasting to a small group of friends and colleagues the archived information about the suffering.

In spring 2020, Zhu and her boyfriend left Shanghai for the U.S. Her first American job was at an independent publication monitoring China’s internet, archiving news and information prone to censorship.

U.S. leaders had long hoped that educational exchanges that brought hundreds of thousands of Chinese students to American campuses would mean democratic ideas would flow back to China and lead to a more open society. Those hopes never quite materialized.

Nonetheless, many young Chinese while abroad get their first uncensored insights into controversies in China’s past, such as the Tiananmen massacre, and current ones, including the suppression of Uyghurs or the demonstrations that mushroomed across major Chinese cities in 2022.

For many little pinks, the patriotic zeal doesn’t go all that deep and sometimes gives way in the face of such exposure, said Weirong Guo, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University who studies the Chinese diaspora.

Guo found that half of the 93 students she interviewed between 2019 and 2021 embraced liberal and democratic ideals. Within this group of liberal-leaning students, a third said they had previously been supportive of China’s governance.

For many, a trigger in their turnaround was Beijing’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Stringent, monthslong lockdowns ultimately led to large-scale protests in late 2022. Overseas, thousands of young Chinese attended demonstrations to support protesters in China.

Zhu, who then lived in Seattle, attended a rally at the University of Washington. “It was shocking to hear so many Chinese chant, ‘Xi Jinping, step down!’ ” Zhu recalled.

She wore a face mask but still worried that she would be recognized. For years, Chinese international students were cautious about expressing criticism of Beijing on university campuses for fear of being harassed by their nationalist peers.

Around the same time, a former Berklee College of Music student, Xiaolei Wu, stalked and threatened someone who was posting fliers around campus supporting democracy in China. Wu was later convicted by a federal jury and sentenced to nine months in prison over his threats. The news was widely circulated on Chinese social media.

In the past few years, Chinese students critical of Beijing have become more vocal, according to some professors. “I’m seeing more openness to liberal ideas among some of my Chinese students,” said Thomas Kellogg, who teaches Chinese law and governance at Georgetown University. He said some students are starting to embrace public protest as a response to the closing space for expression in China.

In 2023, after a Chinese art student scrawled Communist Party slogans on a graffiti wall in London, others soon covered the slogans with Chinese references to the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989 and criticism of Xi and his handling of Covid.

Since 1979, more than eight million people in China have studied abroad, according to official Chinese government data. More than 70% eventually returned to China, where, at least during China’s boom years, many saw better job prospects. While most still go back, university professors said they are seeing more Chinese students who have sought ways to stay on.

In the past two years, more Chinese from different backgrounds have fled China , wary of the gloomy economic outlook or tightening political suppression. For some, a student visa is a ticket out.

Yingyi Ma, a sociologist at Syracuse University and author of “Ambitious and Anxious: How Chinese College Students Succeed and Struggle in American Higher Education,” said most Chinese undergraduate students in a class she teaches plan to pursue advanced degrees so they can stay in the U.S. for a while.

The process of Zhu’s throwing out everything she learned growing up in China has been draining and painful, with each fact-check a shock to her belief system. “It was a process of breaking yourself,” she said. “Because you had to admit that you had been dumb all these years and you’d never questioned what you were told.”

Zhu married her boyfriend in mid-2020. This past summer, she left her job monitoring Chinese social media. She deleted X from her phone and is spending more time with her friends in the U.S.

In the wake of what Zhu sees as her political awakening, a divide has grown between her and her mother. The two now have the kind of arguments Zhu once had with her boyfriend. Zhu feels she has to counter her mother’s growing hostility toward Japan and the U.S., countries Beijing portrays as bullies.

But she picks her battles carefully, remembering her own nationalist fervor not that long ago. “Look, I was there myself,” she said.

Write to Shen Lu at shen.lu@wsj.com