Glad you have a trip to the beach booked? So is your airline. Those who invested in its stock, however, can’t seem to get a break.

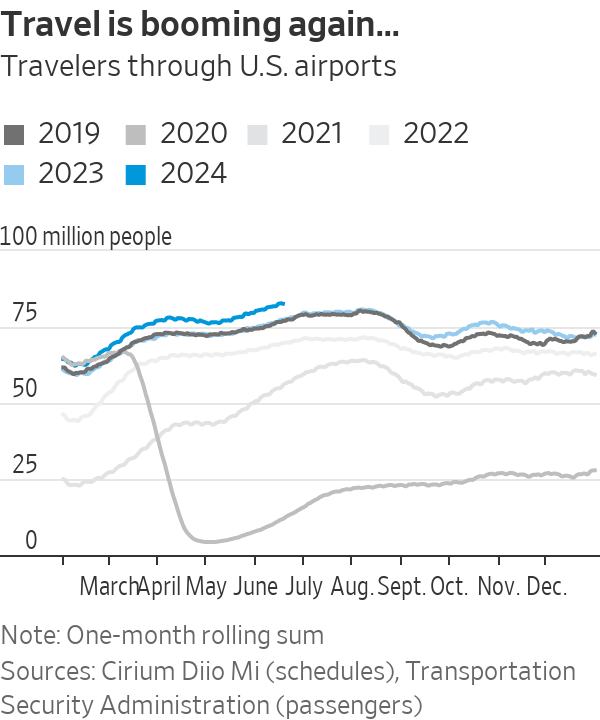

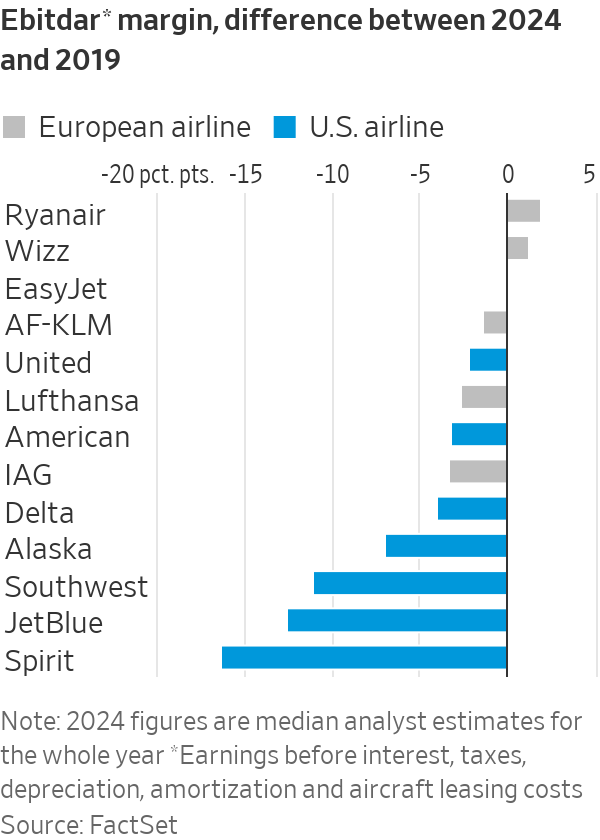

It is shaping up to be the busiest summer season ever in the U.S., and about as strong as 2019’s in Europe, airport passenger data suggests. Yet U.S. airline stocks are down roughly 40% over five years, and European ones about 25%. And this isn’t about capricious investors applying lower valuations to airlines as they rush into artificial-intelligence plays: Carriers are reporting much narrower profit margins.

… but airlines are doing poorly

Budget operators such as Southwest Airlines , Spirit Airlines and Frontier Airlines offer the most painful examples. They used to be money-printing machines, and Wall Street believed they were poised to take market share from legacy players as the industry emerged from the Covid-19 crisis. Instead, they are struggling to stay airborne.

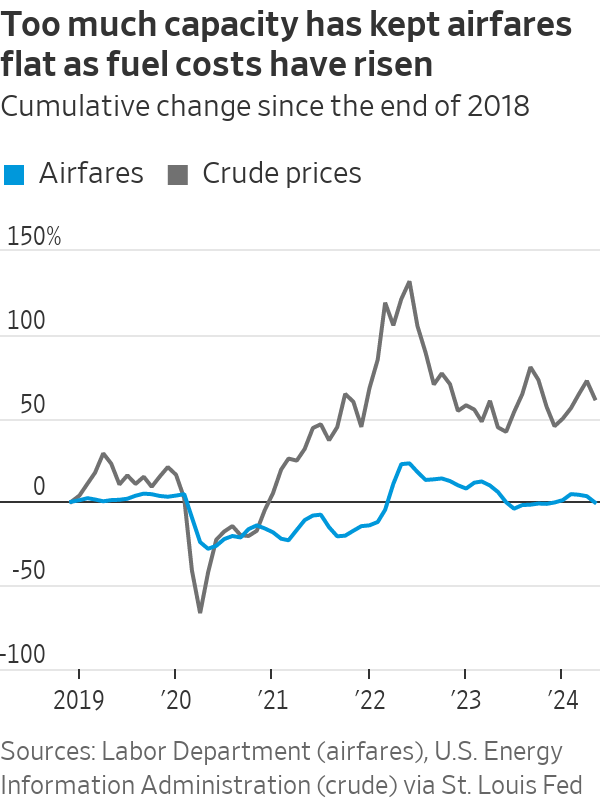

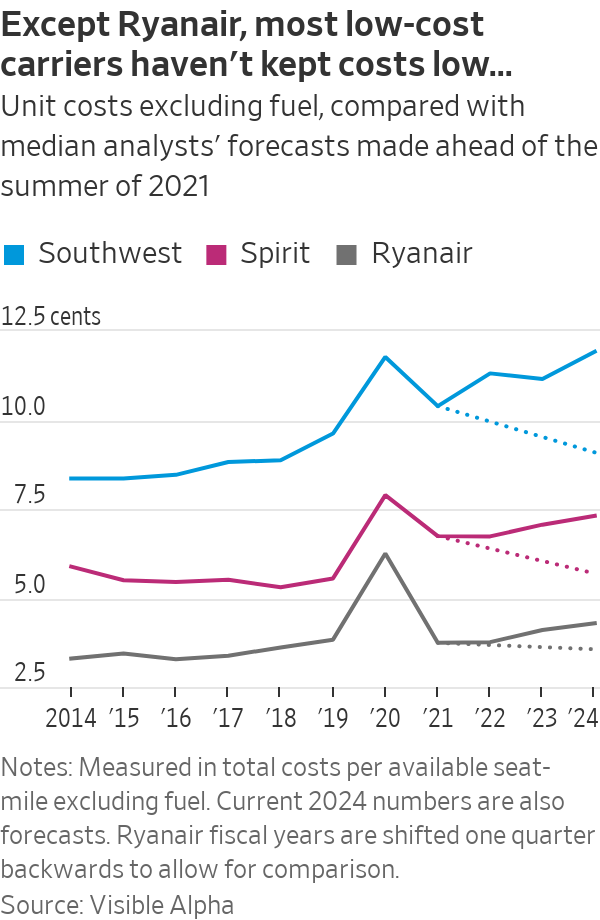

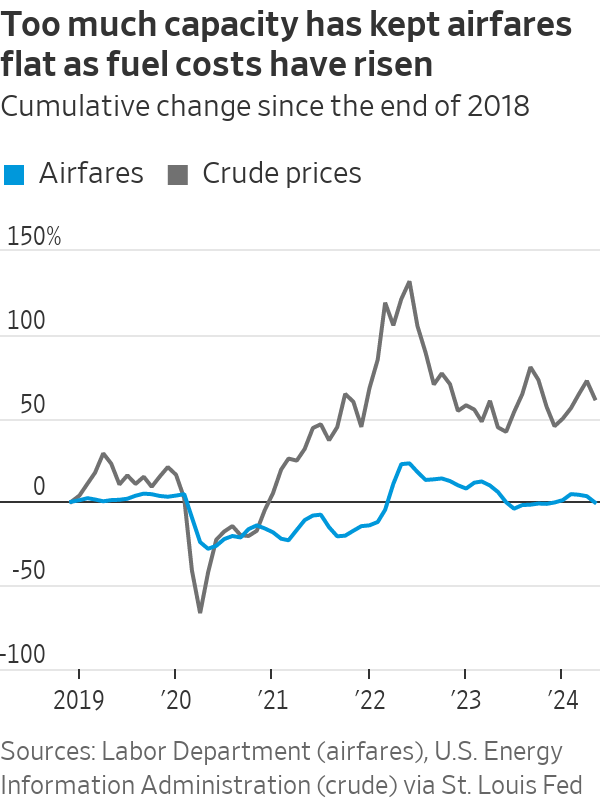

Being low-cost is hard when costs aren’t low . Today, the price of an oil barrel hovers around $80, compared with about $55 before the pandemic. Other expenses have surged too. Take Spirit: In 2021, analysts forecast that its unit costs excluding fuel would fall from 6.7 cents to 5.7 cents by 2024, with the travel rebound sharing the burden of fixed expenses across a broader base, according to Visible Alpha. Instead, they are now expected to be 7.3 cents, close to the Covid peak.

Shortages of pilots and cabin crew have pushed up wages, while weather events and a dearth of air-traffic controllers have led to costly operational disruptions. Problems with engines and aircraft deliveries have grounded planes, increased maintenance bills and slowed the introduction of more fuel-efficient models.

European budget powerhouse Ryanair is the exception: Its decisions to extensively hedge fuel costs and limit job cuts during the pandemic have proven prescient. It has been able to capture a lion’s share of Europe’s “basic economy” trips, particularly in sunny spots such as Italy, where its market share has risen from 27% to above 40%.

But most others have struggled to attract cost-conscious fliers. Since the pandemic, the real boom has been in “premium economy”—offerings with extra space and amenities that no-frills operators don’t usually provide. Full-service carriers, on the other hand, have invested heavily in them. This helps explain why Atlanta-based Delta Air Lines , which has refined the art of providing a premium experience, isn’t doing as badly on the stock market as its peers.

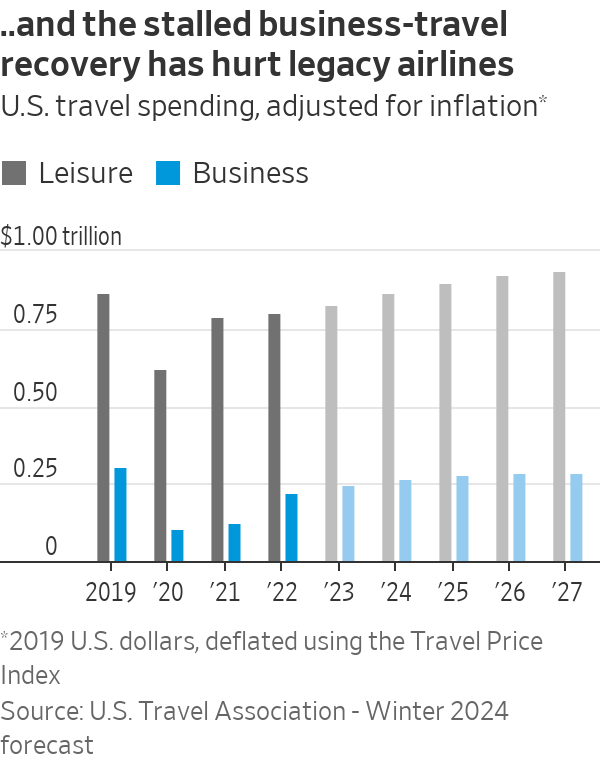

So why aren’t legacy airlines soaring? The catch is that the premium economy boom is partly replacing business-class travel , which was even more of a moneymaker. When travelers book on a company’s dime, they care less about price.

So why aren’t legacy airlines soaring? The catch is that the premium economy boom is partly replacing business-class travel , which was even more of a moneymaker. When travelers book on a company’s dime, they care less about price.

While videoconferences haven’t made business trips redundant and airlines have been reporting higher company bookings for a couple of years now , actual spending on corporate travel has hit a wall. The latest forecast by the U.S. Travel Association suggests that, in inflation-adjusted terms, it will be 13% lower this year than in 2019— many analysts predicted a 15% shortfall at the onset of the pandemic—and then remain flat.

The bigger issue, however, is that airlines have forgotten the lessons learned before the pandemic and have taken hot tourism demand as a signal to expand aggressively. For July, the scheduled supply of seats is running 8% and 0.4% ahead of 2019 levels in the U.S. and Europe respectively, according to Cirium Diio Mi.

Indeed, overcapacity is a bigger problem for U.S. airlines, which explains their worse performance. For example, American Airlines , which has long focused on price and range of destinations ahead of premium offerings, announced an ambitious intra-U.S. expansion in April. Its shares are down 18% this year.

Today’s unbundled “basic economy” tickets allow legacy operators to compete head-to-head against low-cost ones. Another problem is that higher-capacity narrow-body planes have replaced regional jets on many routes since 2019, an analysis of Cirium data suggests. The result is that U.S. airfares, which rose as the recovery gathered pace in 2022, are now back where they were in 2019.

Many airlines are now taking steps to curb supply. Also, Boeing ’s woes, combined with Airbus ’s inability to produce aircraft faster, should constrain the supply of seats for years to come. Many analysts theorize that this will result in permanently higher fares.

Still, investors should tread cautiously when venturing beyond best-in-class names such as Ryanair and Delta. Just like summer flights, airline stocks often come with hidden charges.

Write to Jon Sindreu at jon.sindreu@wsj.com