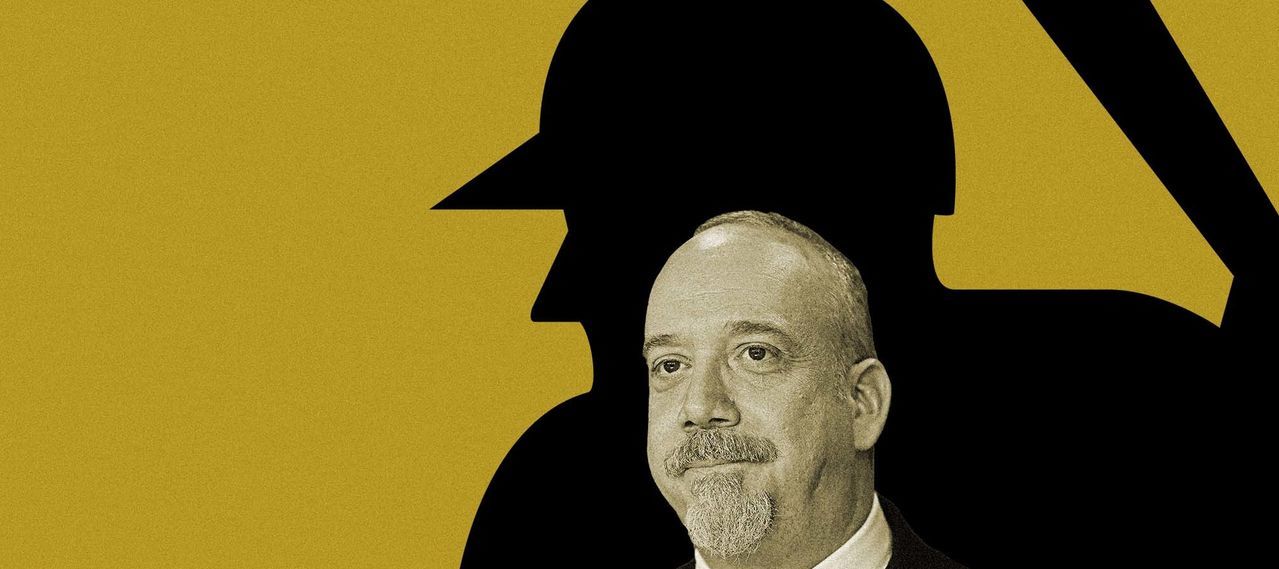

Seven years before his Academy Award-nominated performance as a curmudgeonly teacher at a New England boarding school in “The Holdovers,” Paul Giamatti starred in a small indie drama called “The Phenom.” He played a sports psychologist tasked with trying to help a troubled young pitcher overcome a sudden inability to throw the ball anywhere near the plate.

The little-seen film is a footnote in an acting career that has spanned more than three decades and could reach a new pinnacle with a win at the Oscars on Sunday. But it holds a special distinction on Giamatti’s résumé: It’s the only time the son of a baseball commissioner has appeared in a baseball movie.

“I’m sure we could analyze it in a Freudian way, like why did he do a baseball movie?” said Noah Buschel, who wrote and directed “The Phenom.” “The baseball movie he ended up doing was actually not a baseball movie. It was about fathers and sons.”

Bart Giamatti, Paul’s father, was perhaps the least likely person in baseball history to serve as commissioner. He wasn’t a bulldog labor lawyer like Rob Manfred, an influential team owner like Bud Selig or a high-powered executive like Fay Vincent. He was a respected scholar and professor of English Renaissance literature whose passion for the arts might only have been surpassed by his love for baseball.

When Bart Giamatti’s name surfaced as a candidate to become president of Yale—a position he held from 1978-1986—he responded, “The only thing I ever wanted to be president of was the American League.” (His wish nearly came true; Giamatti spent two years as president of the National League.)

Giamatti’s tenure as commissioner was memorable. He is the man who banned Pete Rose from baseball for life, one of the sport’s single most consequential decisions of the past 35 years.

But his time in the job was also brief, which could explain why his relationship to a beloved Hollywood star remains largely unknown to the public. A week after Giamatti banished Rose—and just five months after he assumed office—he died of a heart attack at the age of 51.

Paul Giamatti was 22 at the time, still several years away from earning his master’s degree from Yale’s drama school and even further from his breakout part as Kenny “Pig Vomit” Rushton in 1997’s “Private Parts.” As a result, Bart Giamatti never saw either of his two sons achieve success in a famously ruthless business. Paul’s older brother, Marcus, is also an actor, known best for his regular role on the CBS series “Judging Amy” from 1999-2005.

“He was really worried because he knew how hard it was,” Marcus Giamatti said. “He probably wished that we had done something that wasn’t such a struggle.”

Though Bart Giamatti supported Paul’s aspirations and believed he had a chance to make it in his chosen profession, there were times when he harbored doubts.

Vincent, Giamatti’s successor as commissioner and a close friend, recalled Giamatti once coming to him to seek some advice. Instructors at Yale were saying that Paul was unusually gifted, but Bart wanted to know if Vincent, a former chairman of Columbia Pictures, thought he really was that talented.

“I said, ‘Well, if he is, it’s like baseball,’” Vincent said. “If he is a really good baseball player, there’s no way he can hide it. It will come out. And when it does, people will go after him for his skills.”

Paul Giamatti really was that talented. To those who knew Bart, that didn’t come as a surprise.

Bart Giamatti had the acting bug too, even meeting his future wife, Toni, when they were castmates in plays at Yale. Marcus Giamatti said he believes it was a musical adaptation of “Cyrano de Bergerac” that sealed their romance. Bart had a small role. Toni was the lead.

Marcus Giamatti said he never discussed with his father why he never pursued acting professionally, though by all accounts he could have. Instead, Bart Giamatti focused on his academic interests, particularly the work of the English poet Edmund Spenser.

His ability as an actor manifested in other ways. Vincent said Giamatti’s strength as commissioner was his ability to connect with people with whom he seemingly had little in common, like baseball’s umpires. Vincent called him “a born actor.”

“Bart could play any role that he wanted to play,” he said. “Paul’s genius is to some extent genetic.”

When the major-league owners were searching for a new commissioner in 1984, a friend suggested to Selig that he speak with Giamatti. By then Giamatti had already written “The Green Fields of the Mind,” an essay about the romance of baseball that begins, “It breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart.”

Selig and Giamatti met for dinner in New York, replaying in excruciating detail the summer of 1949, when their favorite childhood teams—the Yankees for Selig, the Red Sox for Giamatti—battled for the AL pennant. Selig came away convinced Giamatti belonged in baseball. In 1986, he arrived.

“He wrote and spoke as eloquently about baseball as any human being ever has,” Selig said.

Paul Giamatti has said he isn’t much of a baseball fan these days, but Bart passed on his love of baseball to Marcus, who says the game was the way he connected with his dad.

In “The Holdovers,” however, Giamatti channels his father—in a way. His character, Paul Hunham, teaches classics in the same sort of academic environment that he grew up in. The film’s director, Alexander Payne, has said that the part was written for Giamatti. It has garnered him the second Oscar nomination of his career and the first in the best actor category.

But while Paul Hunham and Bart Giamatti shared a passion for history and literature, they differ in at least one key way: Bart Giamatti wasn’t nearly as grumpy as the character his son portrayed.

“Who’s going to be like my father?” Marcus Giamatti said. “Nobody.”

Write to Jared Diamond at jared.diamond@wsj.com