NARSAQ, Greenland—A small group of directors from an Australian company traveled to the southern tip of Greenland recently, where they have been planning to extract rare-earth minerals from one of the world’s richest deposits for more than two decades.

They didn’t get as far as they had planned.

The delegation traveled to the town of Narsaq, home to 1,300 people, by helicopter, the only feasible means of transportation in February. In subzero temperatures, a thick blanket of snow covered the mountain pass, rendering the road inaccessible and preventing the company representatives from visiting the site of the mine.

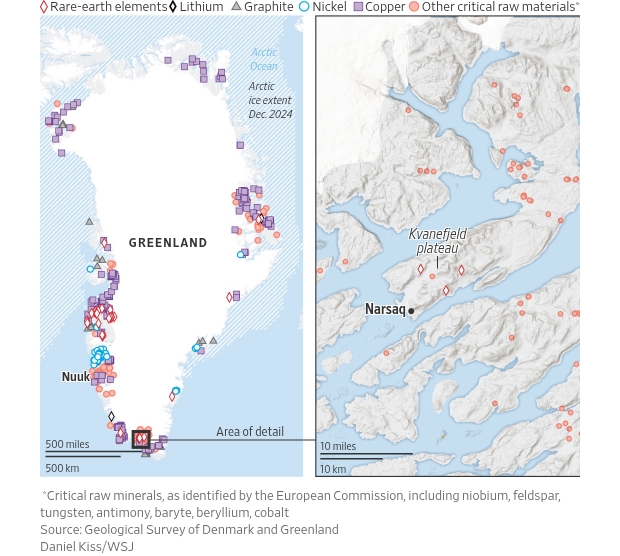

Teeming with underground riches, Greenland might set the scene for a modern gold rush. President Trump, for one, covets Greenland’ s deposits of critical minerals, some of the largest in the Western Hemisphere. But as the visiting Australian company, Energy Transition Minerals , has discovered, securing them is a daunting task.

Kvanefjeld, the site of the billion-year-old solidified magma in the mountains above the town of Narsaq, contains an estimated 1 billion tons of minerals, enough to potentially transform the global market for rare-earth elements, used in such things as electric vehicles, jet fighters, wind turbines and headphones.

To see Kvanefjeld up close, a Wall Street Journal reporter and photographer rode snowmobiles through a pathless gorge below the frozen plateau as the wind blew gusts of snow powder over the ridge. Forty-five minutes into the valley, local guides pointed out the mine entrance about 50 yards up the mountainside, hidden behind several feet of snow.

Mining companies in Greenland operate in one of the most challenging environments in the world because of the Danish territory’s sparse infrastructure, hostile weather and a tricky political climate. Mining here is expensive, and few investors are willing to pay for it given the uncertainties.

Despite its extraordinary mineral wealth, Greenland has only two active mines: a gold mine in commissioning phase and a mine producing anorthosite, used in fiberglass, paints and other construction materials. A ruby mine closed last year owing to bankruptcy. Greenland has extended around 100 mining licenses, mostly for exploration.

“Investing in Greenland is not for the faint of heart,” said Brian Hanrahan , chief executive officer of Lumina Sustainable Materials, which operates the anorthosite mine on the west coast of Greenland. “The local logistics are incredibly complex.”

Building a mine here involves high startup costs, and has to be done from scratch in rugged terrain. Greenland is nearly one-fourth the size of the U.S., and about 80% of it is covered by ice, with deep fjords and ice sheets up to a mile thick. There are no roads between settlements, and shipping is treacherous because of floating ice off the coast.

Bureaucracy is a hindrance, too. The process of granting licenses to foreign companies to mine is lengthy and cumbersome. While applying for licenses, companies need to keep employees on payroll with benefits. With a population of 57,000, Greenland’s labor market is tight.

In a previous role as vice president of the French mining company Imerys , Hanrahan oversaw 270 operating sites in 70 different countries.

“None of them were as complex as Greenland. It’s more challenging to manage this one site than dozens of those other sites combined,” he said.

Exploration is an ancient and inherently risky form of economic speculation, even more so in Greenland. Prospectors have circled the island since the 1800s, and the U.S. first evaluated its resource potential in 1868. But as opposed to other remote mining locations, such as Alaska and Canada, Greenland has no history of exploration done by local companies. That cools the enthusiasm of foreign investors who prefer to know what they are buying.

While Greenland attracts funding for exploration, it struggles to obtain the kind of institutional investment for exploitation seen elsewhere, said Charlie Byrd , investment manager of Cordiant Capital, which backs Lumina’s anorthosite mine. “That can become a sort of dark financial hole.”

Greenlandic government officials have in recent years visited Canada and Australia to court dozens of multinational mining companies. Many are tentatively interested, but want more data on its mineral deposits.

Breaking China’s monopoly

Extracting Greenland’s minerals is about more than profit; it is about resource control. Western governments are eager to break China’s dominance of the global market for rare earths and other minerals, which it could wield as a weapon in a trade war.

China produces roughly 60% of the world’s mined rare-earth minerals, and has tightened its grip on the entire supply chain. Beijing controls 91% of refining activity and 94% of production of magnets, the main product rare earths are used for. This dominance allows Beijing to keep prices low, making it harder to profit from Greenland’s rare earths.

“Greenland is host to some of the largest rare-earth resources known to exist globally, which have potential to supply virtually all the foreseeable needs of North America and Europe for decades to come,” said Ryan Castilloux , managing director of Adamas Intelligence, a consulting firm that advises on strategic metals and minerals. “It offers a real strategic upside for not just Europe, but the entire industry outside of China.”

Greenland contains an estimated 43 of the 50 critical minerals that the U.S. considers vital to national security. President Trump has insisted that the U.S. should own the Arctic island. Greenland and Denmark have rejected Trump’s bid to buy the island, but Greenlandic Prime Minister Múte B. Egede has welcomed American investment in his country’s mining industry.

Uranium U-turn

On top of all the usual hurdles to mining in Greenland, Energy Transition Minerals is dealing with a political curveball the company didn’t expect. In 2007, the company received a license to explore minerals in Kvanefjeld from the Greenlandic government, which saw mining as a chance to boost its economy.

Then, in 2021, Egede, a politician from Narsaq, was elected prime minister on promises of banning uranium mining. The law the government passed the following year prohibited mining minerals with a certain content of uranium, which occurs naturally in the rare-earths deposits in Kvanefjeld, effectively halting the project.

Daniel Mamadou , the company’s Singapore-based managing director, said that when he spoke to the Greenlandic government and objected to the uranium law, he was told by the minister for natural resources that the company had known the risks going in.

Mamadou acknowledged mining was speculative. “But the gamble is not on political grounds. The gamble is, are you gonna make a discovery, yes or no? And the discovery was made years before,” Mamadou said.

Energy Transition Minerals says it has spent $90 million on exploring Kvanefjeld and accuses the government of expropriation. The company has filed an arbitration case against Greenland and Denmark, demanding the right to mine or compensation of $11.5 billion—nearly four times Greenland’s gross domestic product.

The departing government, which passed the bill, has denied expropriating Kvanefjeld, and says that while mining could strengthen Greenland’s bid for independence, protecting the environment is vital for its tourism and fishing industries.

Granting American companies licenses to mine rare earths could be a way for Denmark to make concessions to the Trump administration, while helping Greenland diversify its economy, said Lone Dencker Wisborg, who served as Danish ambassador to the U.S. when Trump tried to buy Greenland in 2019. But the legal dispute in Kvanefjeld could spook investors, she said.

When directors from Energy Transition Minerals visited Narsaq in February, they were met near the icy helipad by protesters in brightly colored vests emblazoned with a logo spelling “Uranium? No, Thank You” in Greenlandic.

The mining executives went on a charm offensive in Narsaq, inviting influential locals for dinner and locally brewed beer and gin at the town’s only hotel. Among the guests was a prominent cattle farmer, to whom they pitched a plan to settle hundreds of workers on his land.

If realized, the mine would transform the small community in Narsaq, where residents mostly make a living off sheep farming and fishing.

The company says it will employ 1,000 people during construction of the mine, and 400 during operation, requiring labor from other parts of Greenland, and likely abroad. After blasting an open-pit mine in the bedrock of Kvanefjeld, the mining company would extend roads into the mountains and build a port to ship out the ore.

The company has proposed storing 100 million tons of radioactive contaminants in a mountain lake walled off by two 45-meter dams. Experts have questioned the safety of the proposal, and similar so-called tailing ponds have caused disasters elsewhere.

Many among the Inuit population of Narsaq are concerned about contamination of drinking water, plants and wildlife. “We live off nature as our forefathers have done for generations. We will be forced to move,” said Avaaraq Bendtsen, a 25-year-old archaeology student. “Think about the indigenous people as well. This is our land. It is our mountain.”

Others worry about dust from the mine, about 4 miles from town. “We want to be able to hang our laundry outside and open our windows,” said John Geisler, a shop assistant, as he pushed his toddler in a stroller up an icy hill in town. “We need to think first and foremost about our health.”

Local supporters in Narsaq hope the mine will bring much-needed employment to a town that has regressed in recent years. The local fish factory closed more than a decade ago. Many young people have moved to larger towns. Unemployment, otherwise rare in Greenland, has increased, which some locals say has led to alcoholism, crime and poorer overall health.

“This negative spiral is also unhealthy for society,” said Josef Petersen, a 49-year-old manager of a vocational school in Narsaq. “Now that people have rejected the mining project, then what? Is this the life you want?”

Write to Sune Engel Rasmussen at sune.rasmussen@wsj.com