Two years after she started taking Xanax, Dana Bare began having panic attacks like never before.

Her memory started slipping. Her husband had to remind her how to make a sandwich. Bare’s ailments cycled her through emergency rooms and puzzled specialists, some of whom thought she was mentally ill or had cancer. No one knew what to do other than up her Xanax dose, to 2 milligrams a day at one point.

The popular pills had been a blessing at first when her general practitioner prescribed them for mild insomnia more than a decade ago. Bare was a busy mother of five running a charity based in Smith County, Tenn. Xanax helped sleep come easy.

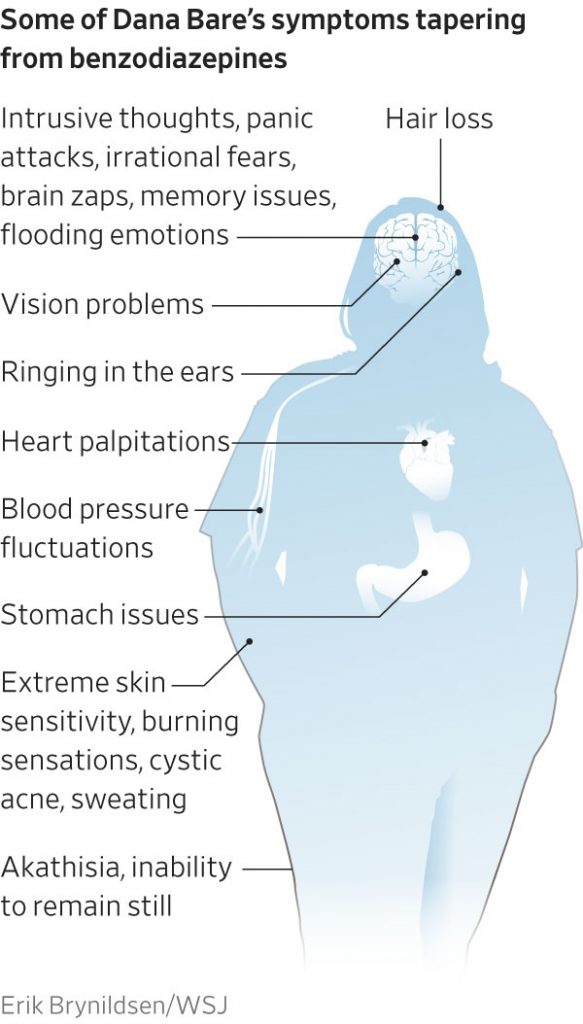

Over time, though, her nervous system developed a debilitating physical dependence on the drug. When she tried to quit after five years, crippling symptoms consumed her. “Brain zaps” hit her like electric shocks. Shower water jolted her so badly that she would suffer hourslong panic attacks and at times writhe in pain until she passed out.

“Never forget how much I have always loved you, but don’t spend too much time missing me,” Bare wrote to her oldest daughter in 2018, when she worried she might die amid her two-year journey to get off the drug. “There has never been anything greater than being your mama.”

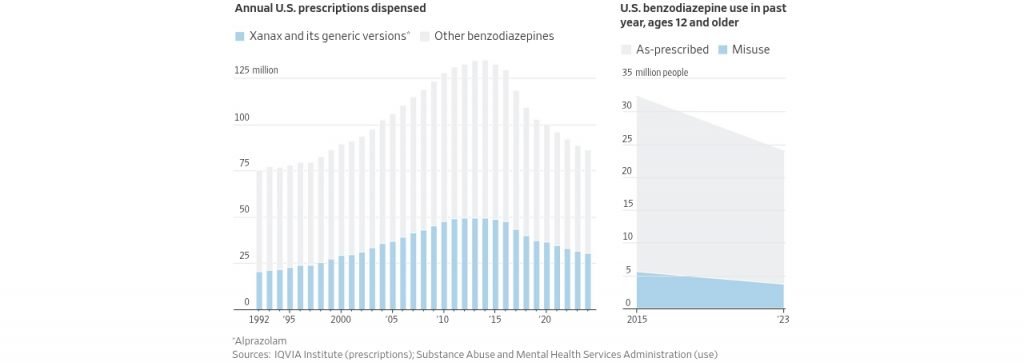

Over the past six decades, hundreds of millions of people have taken Xanax (the brand name for alprazolam) or one of its cousins in the benzodiazepine family—Klonopin (clonazepam); Ativan (lorazepam); and Valium (diazepam)—to lull them to sleep or deliver instant calm in an age of abiding anxiety.

Psychiatrists and primary-care doctors regularly prescribe the drugs for everything from mild anxiety to insomnia, making benzodiazepines some of the most commonly prescribed psychiatric medications in America. The pills’ omnipresence has left a mark on pop culture, turning up in Lil Wayne songs and HBO’s “The White Lotus” as bearers of chemical tranquility.

But as concerns increase about potential adverse effects of these drugs, some patients who try to quit are suffering what amounts to a hangover they can’t escape.

The problems are far from universal, but a subset of patients are finding it is almost impossible to taper off without suffering through anxiety that is far worse than before, including cycles of agitation that make it impossible to sit still, memory loss, nausea and more. Doctors describe the unique impact of benzodiazepine withdrawal for them as something akin to a neurological disorder.

While Xanax is notoriously misused as a party drug, most of the people suffering these symptoms are, like Bare, law-abiding patients. They took the medicines as prescribed for weeks, months or years, and built up a physical dependence that often led to doctors upping their doses.

“This is something we’re seeing specifically with benzodiazepines and it’s causing a range of symptoms across the entire neurological system,” said Dr. Alexis Ritvo, the medical director of the Alliance for Benzodiazepine Best Practices, a nonprofit organization , and assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Estimates of the size of the problem are all over the map. In a presentation late last year citing older studies, Ritvo said that between 15% and 44% of chronic benzodiazepine users experience moderate to severe withdrawal symptoms. A smaller group—10% to 15%—suffer from protracted symptoms that can last for months and continue long after these patients taper off the drugs. The pain is so bad for some that they take their own lives.

In 2023, a group of advocates and scientists including Ritvo proposed a term for the protracted condition: benzodiazepine-induced neurological dysfunction, or BIND.

There is a shortage of research into long-term use of the drugs—many of which are now generic—or what causes some people to experience devastating consequences from withdrawal, said Dr. Donovan Maust, a geriatric psychiatrist and professor at the University of Michigan.

“There’s lots of evidence that people can stop and they’ll be fine,” Maust said. “But you have these pockets where people have been profoundly affected in a very bad way.”

The Wall Street Journal spoke to nearly four dozen doctors, researchers, and patients or family members of patients who had been prescribed benzodiazepines. The patients ranged from doctors to mail carriers, veterans to tech workers, business executives to new mothers, all of whom say their lives were turned upside down by crippling effects of the drug.

Benzodiazepines have important uses. They are highly effective at preventing and treating life-threatening conditions such as seizures or alcohol withdrawal. Some psychiatrists say they can be effective as long-term treatment for certain chronic anxiety disorders.

See How Benzodiazepines Quiet the Brain

Many doctors say the drugs are too often prescribed for conditions they aren’t effective at treating, and often for too long. Studies dating back decades have shown that they have no clear advantage over a placebo for better sleep, one of the most common reasons they are prescribed.

Many guidelines recommend only short-term use of benzodiazepines—no more than four weeks. The U.K.’s National Health Service doesn’t offer prescriptions of Xanax; it stopped years ago amid growing concern about dependencies. (It does offer other benzodiazepines, with limitations.)

About a quarter of people who take benzodiazepines in the U.S. use them for four months or more, according to a 2015 study in the journal JAMA Psychiatry. A 2020 federal government report found that about half of office visits for benzodiazepine prescriptions were to primary-care physicians—doctors with fewer resources and training to manage psychiatric drugs.

“These were never really designed to be long-term medications,” said Dr. Haran Sivakumar, an addiction medicine specialist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York who also has his own private practice.

Some doctors who used to prescribe benzodiazepines regularly said they turned away from them as they saw patient after patient suffering serious withdrawal.

“Everybody knows that if you take benzos and you stop, you get withdrawal. What people don’t tend to know is that in some people, long-term use of benzos can be neurotoxic and damage the brain,” said Dr. Peter Martin, a professor of psychiatry , behavioral sciences and pharmacology at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. “Even when withdrawal is gone, there are cognitive deficits left over.”

Martin, who has been treating patients since the mid-1970s, said, “I’m an expert on this, and I was never aware that there are these patients who have long-term consequences of benzodiazepines. I personally feel a little negligent myself. I was not aware of it, and I should have been.”

After a rise in complaints, in 2020 the FDA required drug manufacturers to add a warning on benzodiazepines about the serious risks of abuse, physical dependence and withdrawal reactions.

But nearly 24 million Americans are still using them. More than 86 million prescriptions were written last year, according to the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science.

‘I Consider This to Be Murder’

Within a few weeks of starting a Xanax prescription in 2015, Dr. Christy Huff’s body was racked by an anxiety she couldn’t explain. The cardiologist had been prescribed 0.25 milligrams of Xanax by her primary-care doctor for trouble sleeping, but no one had warned her about the risks.

She did some research and realized she was experiencing withdrawals between doses. Her heart was racing, her body shook, and she struggled to breathe and swallow. She lost 15 pounds. “I looked like a skeleton,” she wrote in a 2016 blog post.

Her doctor prescribed her more Xanax: 0.5 milligrams up to three times daily. It didn’t help. She sought to get off the drug instead , and a psychiatrist helped her cross over to Valium, a longer-acting benzodiazepine considered easier to wean off of.

She was bedridden for months as she “micro-tapered” off Valium, filing down pills little by little using a scale. She documented 79 different withdrawal symptoms in tweets, from akathisia—an inability to stop moving her arms and legs—to dizziness. Walking felt like moving stone, because her muscles went into spasms, she wrote. She struggled to transfer laundry from the washer to the dryer.

It took her more than three years to stop. After that, she still had tremors—“buzzing like I’m plugged into an electrical socket”—a pounding heart and anxiety in the mornings. She joined a nonprofit group, the Benzodiazepine Information Coalition, as a volunteer medical director, contributing to research and seeking to highlight the harms of the drugs.

Huff, who had graduated at the top of her class as a physician, was outraged that she and other doctors were untrained about the potential ill effects of benzodiazepine use and “some of the most serious risks are not mentioned in the FDA Label —specifically that patients can suffer disabling neurological damage from benzodiazepines, which in some cases may be permanent,” she wrote in 2019.

In late 2023, she took a common “beta blocker” drug, which blocks adrenaline, and was besieged by adverse effects, including muscular atrophy and anxiety “bursting from my chest.” She surmised that “prior damage from benzodiazepines came into play.” Last March, she killed herself. Her husband later found a note she had written on her phone.

“If I end up taking my life or dying of natural causes, I consider this to be a murder,” she wrote, blaming damage from prescription drugs. “My body has been completely destroyed. I would never leave my family and beautiful daughter if I had another option.”

Early Success and Early Warnings

Huff’s tragic experience is a far cry from the early success of Valium, marketed aggressively in the 1960s and 1970s as a wonder drug that could wipe away worries more safely than barbiturates. The little yellow pill, stamped with a V, became a pharmaceutical blockbuster and cultural icon.

Valium use peaked in the late 1970s, as concerns about its potential for dependence and abuse proliferated. On its heels came Xanax. Approved by the FDA in 1981 and marketed by pharmaceutical company Upjohn, it acted powerfully and quickly to relieve anxiety. (Upjohn was later subsumed into Pfizer ; Xanax is now made by Viatris .)

There were some early warnings. At the end of one clinical trial, more than a third of patients who took alprazolam experienced withdrawal symptoms. Many had more panic attacks after stopping the drug than those on a placebo or than they had before the trial began. Still, the drug was approved as a treatment for panic disorder in addition to anxiety.

Other scientific studies had sounded warnings about benzos. Dr. Heather Ashton, a British physician and psychopharmacologist, devoted much of her career to seeing and studying patients who came to her for help quitting the tranquilizers. In a 1984 article in the British Medical Journal, she reported that benzodiazepine patients sometimes suffered from a protracted form of withdrawal unlike other drugs.

“Benzodiazepine withdrawal is a severe illness,” she wrote. She later produced a manual for tapering from benzodiazepines that is now used around the world.

A Viatris spokesperson said the safety and efficacy of Xanax have been proven in studies and “ongoing post-marketing surveillance in patients with anxiety disorders.” Prescribing information in the U.S. includes recommendations for discontinuing treatment over time, the spokesperson said.

The Medical System’s Failures

Jezel Rosa, a psychiatric nurse practitioner, estimated that more than half of the people she saw between 2021 and 2023 at a community mental health clinic servicing mostly low-income families in Florida were on benzodiazepines. Rosa, who now helps taper patients off the drugs, said in the decades after they became generic, benzodiazepines became a reliable and easy way for doctors to treat people from all walks of life.

“To help someone quick and fast, that is the tool in your toolbox,” Rosa said. “You give them a benzo.” There’s often no “informed consent” about long-term risks, she said.

For many patients struggling with benzodiazepine withdrawal, visits over the years to emergency rooms, doctors and specialists cost lots of money without providing relief or answers. Patients sometimes turned to rehab or detox centers for help in getting off the drugs, but many said the centers didn’t always know how to help them.

Even a trip to Cirque Lodge in Utah, a high-end rehab facility frequented by A-listers, didn’t take care of insurance executive Greg Gelineau’s intense withdrawal from Klonopin, which he’d been taking as prescribed for better sleep along with Ativan for a couple of years.

While Cirque got him off the medicine safely, Gelineau said the facility’s specialists didn’t understand the side effects of withdrawal and accused him of noncompliance with their program when he refused to come on a long hike with others. “I could barely function. I called my wife and said goodbye, as I didn’t think I could survive the intense suffering.”

After several days in a local hospital, Gelineau eventually landed at a treatment center that helped him deal with the more intense aftereffects.

His recovery, which he says is now complete, cost him more than $100,000.

The Veteran

A few years after Patrick Lantis returned home from a tour in Iraq, he had a major anxiety attack. He visited a psychiatrist at the Department of Veterans Affairs, who prescribed Ativan. A counselor at the VA pharmacy explained to Lantis how to take the drug, and the dangers of abusing it, but didn’t mention risks of physical dependence.

Lantis settled into a routine of taking a 1 mg pill in the morning, and one at night every day. The anxiety subsided.

When Lantis had been taking Ativan for about a decade, he started having difficulty concentrating and remembering names and words. He learned that cognitive impairment was a potential effect of long-term use and decided he should wean himself off the drug.

Two months after his first attempt, he was suddenly overtaken by anxiety, worse than he had ever experienced. His heart raced. He was sweating, and felt nauseated and weak, like he had the flu. He couldn’t sleep.

The fear and the panic felt “like somebody is holding a gun to your head,” Lantis said. He asked his father to take his handgun away, afraid that he might turn it on himself.

A psychiatrist put him back on Ativan and his symptoms dissipated in a few hours.

The second time, Lantis tapered more slowly, working with a psychiatrist outside the VA and a tapering coach. He was down to about 50% of his original dose by last October when once again, he developed paralyzing anxiety. His wedding was two weeks away. Unable to function, he went back on his full dose.

Lantis, a 40-year-old biologist in Omaha, Neb., who specializes in wetland conservation easements, has transferred to 20 mg of Valium a day and is preparing to taper for a third time, working with a therapist and psychiatrist. He and his wife are about to build a house and hope to have a baby.

“There is this huge difference between physical dependence and addiction,” he said. “I’m not taking it because I’m getting a high off of it.”

A Brewing Backlash

In 2020, the FDA updated a boxed warning—its strongest safety alert—about benzodiazepines, nearly 40 years after its Xanax approval. There had been a spike in reports to the agency of adverse effects involving the drugs, from 1.8 million in 2017 to 2.2 million in 2018, and a rise in calls to U.S. poison control centers about benzodiazepine withdrawal. The agency had already warned in 2016 that combining benzodiazepines and opioid medicines could be deadly.

The FDA called for proper guidelines for clinicians to help patients taper off the drugs and funded the American Society of Addiction Medicine to develop them. The new guideline , published this month by ASAM, recommends that patients who have been taking benzodiazepines regularly initially reduce their dose by 5% to 10% every two to four weeks and adjust the pace based on symptoms with each dose reduction. These patients should never quit benzodiazepines abruptly, it said.

Six years after taking her last dose, Dana Bare, 44, still struggles with panic attacks and agoraphobia. She is traumatized from the time that she spent in a psych ward in 2017 after a doctor briefly put her on an antidepressant on top of the Xanax, which led to intrusive thoughts of hurting her children. She had to quit running her charity and fell more than $10,000 in debt; now she cleans businesses in the evenings, often driven around by her husband.

“I went from being independent and totally functional to just slowly declining into this absolute pit of hell,” Bare said. “Coming off benzos didn’t kill me, but it was the hardest thing I’ve ever went through in my life and traumatized me in ways I’m still suffering with.”

Help is available: Reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (formerly known as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline) by dialing or texting 988.

Write to Shalini Ramachandran at Shalini.Ramachandran@wsj.com and Betsy McKay at betsy.mckay@wsj.com