Shadia Abu Middin had fled Israel’s war against Hamas twice. Then on Dec. 31, Israel told the 44-year-old mother of four in Gaza to run again, but she didn’t know where to go.

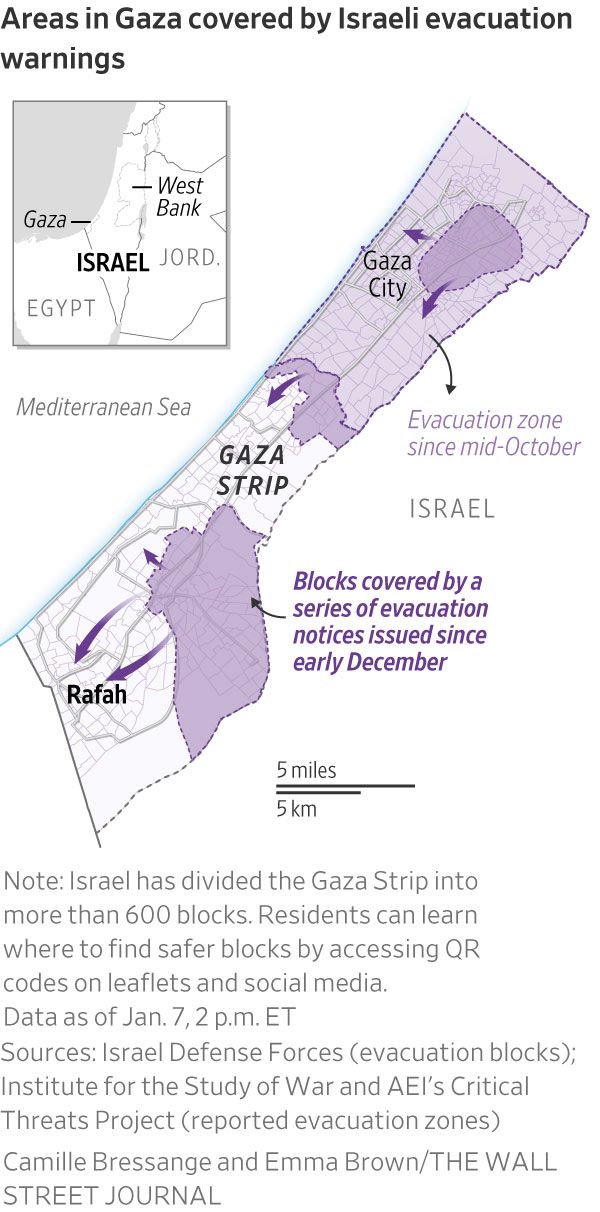

Palestinians are fleeing into an ever-shrinking section of the Gaza Strip as Israel’s offensive enters its fourth month and its military asks the enclave’s residents to leave more areas it says are unsafe. The Israeli warnings are pushing people to concentrate into just one-third of the strip, the United Nations agency for Palestinian refugees says. In effect, the ground available to its 2.2 million people has shrunk to an area slightly larger than the Bronx.

Those fleeing in the most-recent round of evacuations face an even deeper state of confusion and exhaustion than previous waves. Internet and communications systems are limited after months of war. Israel has largely banned the entry of fuel for cars, so Gazans are resorting to carts towed by horses and donkeys.

They are sheltering in abandoned buildings, sleeping in the street or pushing into already crowded U.N.-run schools that serve as shelters. Diseases such as hepatitis are spreading, aid groups say. Food and clean drinking water are scarce and Gazans are chopping down trees for firewood.

Abu Middin and her family, including the four children, left the Nuseirat refugee camp in central Gaza after Israeli aircraft dropped leaflets urging civilians to evacuate. The Israeli military expanded its ground operations in the area in late December, with Israeli soldiers fighting militants in the Nuseirat camp and other locations close to it.

The family packed blankets and some clothes, and first arrived in the nearby city of Deir al-Balah. Concerned that the advancing Israeli military could make Deir al-Balah its next target, they began scouting for other options—this time in the city of Rafah at the southern end of the strip that borders Egypt.

“Rafah is so crowded we barely could find a spot to pitch a tent,” said Middin.

They found one in a tent camp near Rafah and fashioned their own tent from plastic sheeting, and they are searching for a more permanent place to live, she said. Other families received tents handed out by aid agencies.

Around 1.9 million people, or 85% of the strip’s population, have been displaced by the war, the U.N. says. A million of them are squeezed into Rafah, an area with a prewar population of 275,000 that has become the epicenter of the humanitarian crisis.

The U.N. and other aid agencies say they face many hurdles in delivering aid to central and northern Gaza because of the fighting. Even in Rafah, which relief agencies reach more easily, humanitarian operations are under immense pressure because of a lack of supplies and other challenges posed by the war.

“The humanitarian community has been left with the impossible mission of supporting more than two million people, even as its own staff are being killed and displaced, as communication blackouts continue, as roads are damaged and convoys are shot at, and as commercial supplies vital to survival are almost nonexistent,” Martin Griffiths, the U.N.’s humanitarian aid chief, said last week.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has said that Israel would need to take control of the Gaza Strip’s southern border with Egypt to prevent Hamas from smuggling weapons into the enclave. If the fighting expands southward into some of the last-available areas of refuge, it could further escalate the humanitarian crisis by pushing people to flee yet again, though it isn’t clear where they would go.

For Israel, the concentration of displaced civilians will shape any future military operation in the area. An Israeli military official said that any effort to seize control of the border would likely be limited to an area about 500 meters to 1 kilometer from the border, and that the army would avoid a large-scale clearing operation in Rafah.

“I don’t think that we’re going to see what happened in the city of Gaza in the south of the Gaza Strip,” said the official, adding that the army would instead wage a long, lower-intensity campaign to erode Hamas’s capabilities in the south.

Fleeing to another country isn’t an option for most people living in the Gaza Strip, whose borders are sealed by both Israel and Egypt. Entry to Egypt is limited to a tiny minority who are able to obtain a special permit. Brokers promising to negotiate exit for Gazans are charging fees that have soared into the thousands of dollars, residents say.

Israel launched its offensive on Gaza in response to the Oct. 7 storming of southern Israel by Hamas militants that killed around 1,200 people, including massacres of partygoers at a music festival and residents of small towns near Gaza. Israel’s military operation is aimed at toppling Hamas from power and it has urged a series of civilian evacuations across the enclave—starting in the north and spreading increasingly to parts of central and southern Gaza.

More than 23,000 people, mostly women and children, have been killed in Gaza since the operation began, according to Palestinian health officials, whose numbers don’t distinguish between combatants and civilians.

Israel initially told displaced Palestinians to go to an area called Al-Mawasi, a stretch of land about 9 miles along the Mediterranean in Gaza. The U.N. says the area is simply too barren and too small to accommodate hundreds of thousands of displaced people. Some Gazans have gone there simply looking for anywhere to stay as the conflict continues.

Israeli officials say the evacuation warnings, issued via social media and in paper leaflets dropped from the sky, are essential to minimize the risk posed to civilians in areas of intense hostilities. They are also aimed at giving the military a freer hand to battle Hamas, which Israel says has embedded itself among the civilian population.

“While the IDF makes these efforts to evacuate the population out of the line of fire, Hamas systematically attempts to prevent the evacuation of civilians by calling on the civilians to ignore the IDF’s requests,” an Israeli military spokesperson said in response to questions about the evacuations, using the abbreviation for the military’s official name, the Israel Defense Forces. Hamas has denied using human shields and says Israel is shelling Gaza indiscriminately.

In the first evacuation order shortly after the war began, Israel urged more than a million people to leave the north of the strip, including the populous Gaza City. The Israeli military said in response to questions that civilians cannot return at this time because “the northern Gaza Strip remains an active and dangerous combat zone, with no change in the situation.”

A second wave of evacuations has taken place since the end of a cease-fire in late November. Under a new approach designed to allow for more limited evacuations, the Israeli military issues warnings using a system that divides the Gaza Strip into a numbered grid.

Some people have remained in the areas covered by the evacuation notices because they are unable or unwilling to leave. The old, sick and wounded might not be able to flee, while others fear the dangers of traveling during the war or are concerned that they won’t be allowed to return home.

Palestinians in Gaza and humanitarian groups also reject the notion that anywhere in Gaza is safe for civilians, pointing to Israeli strikes that have hit areas where the Israeli military has instructed people to go, including Rafah. Since the war began, at least 308 people have been killed and more than 1,000 injured in U.N.-run shelters, according to the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees.

Israel accuses Hamas of operating in and near U.N. facilities and says that it takes steps to protect civilians. Israel also doesn’t say that the areas it has designated for civilians are safe and instead uses language describing them as “safer.”

Even those who manage to reach southern Gaza safely are faced with a dire situation. A U.N. report last month said that 90% of the population was suffering from “high levels of acute food insecurity” with most people skipping meals every day.

“It’s beyond apocalyptic,” said Bushra Khalidi, a policy lead at Oxfam, an antipoverty charity. “It makes you question your entire humanity to hear the stories coming out of Gaza.”

Write to Jared Malsin at jared.malsin@wsj.com