The Federal Reserve approved a quarter-point interest-rate cut Thursday, the latest step to prevent large rate increases of the prior 2½ years from weakening the labor market as inflation eases.

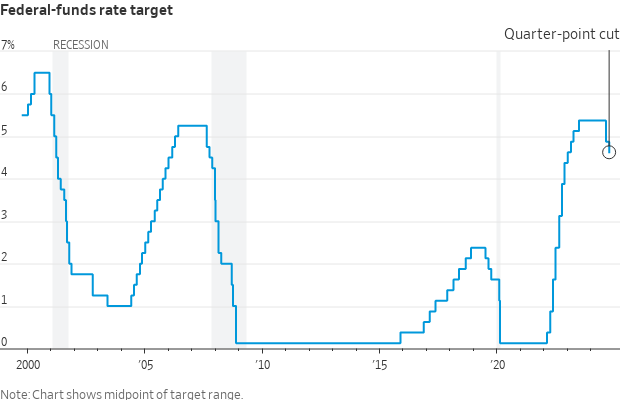

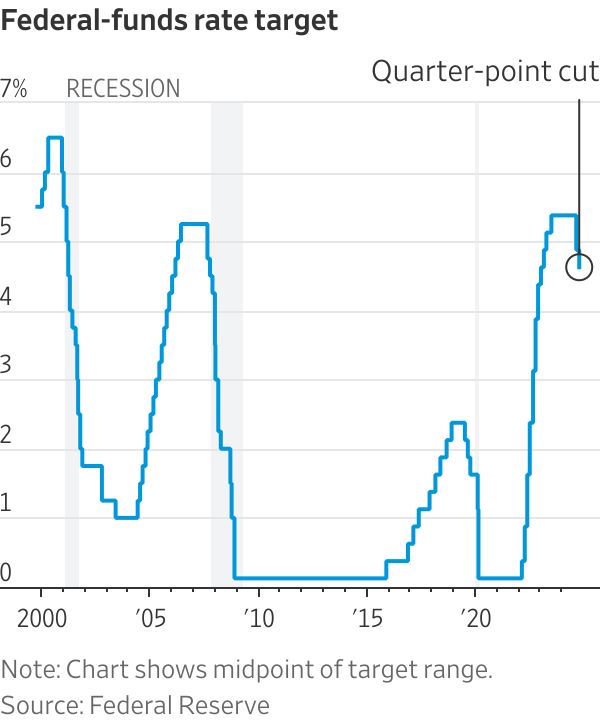

The decision, coming the same week as the election of Donald Trump to a second presidential term, followed an initial cut of a half-point in September and will bring the benchmark federal-funds rate to a range between 4.5% and 4.75%. All 12 Fed voters backed the cut.

Officials have said those moves are warranted because they are more confident that inflation will return to the central bank’s target and because they believe rates are still high enough, even with the latest cuts, to dampen economic activity.

The move was expected. Stocks and Treasury yields were steady after the announcement.

“We are committed to maintaining our economy’s strength,” Fed Chair Jerome Powell said at a news conference. He said officials are confident that with an “appropriate recalibration of our policy stance,” inflation can continue heading lower with a solid economy.

Trump’s election victory this week has the potential to reshape the economic outlook, with presumed GOP majorities on both sides of Capitol Hill enabling a broad shift on taxes, spending, immigration and trade. Economists are divided over whether the mix of policies will boost or weaken growth and drive up prices.

The shift in the outlook , in turn, has fueled questions on Wall Street over whether the Fed will alter its earlier expectation that rates could be steadily dialed lower over the coming year or two.

Since the Fed cut rates in September, longer-dated bond yields have climbed notably, meaning the cost to borrow for a mortgage or car loan has gone up. Yields have increased in large part because better economic data has led investors to reduce their worries about a recession, which could have triggered larger rate cuts.

But some analysts think the bond-market selloff may also reflect concerns by some investors about higher deficits or inflation in a second Trump administration.

Either way, the market has generated an unusual result: Borrowing costs rose after the Fed cut rates. The average 30-year mortgage rate has jumped since mid-September, to 6.8% this week from 6.1%, according to Freddie Mac.

Over a similar time frame, investors in interest-rate futures markets have steadily reduced their expectations over how much the Fed will cut rates over the next year or so. They now see the Fed cutting rates to around 3.6% by 2026, up from an estimated trough of 2.8% in September, according to Citi.

Officials are trying to bring rates back to a more “normal” or “neutral” setting that neither spurs nor slows growth. But they don’t know what constitutes a normal rate. Policies that boost economic activity or prices could also lead officials to conclude that they should maintain a moderately restrictive rate stance. That means they would hold rates somewhat higher than a normal or neutral level.

Before the 2008-09 financial crisis, many thought a neutral rate might be around 4%, but after the crisis and an extremely sluggish recovery, economists and Fed officials concluded the neutral rate might be closer to 2%.

Interest-rate projections that officials submitted in September show most of them expected that if the economy expanded solidly with inflation continuing to cool , they could cut rates to around 3.5% next year.

Inflation based on the Fed’s preferred index was 2.1% in September, from a year earlier. A separate measure of so-called core inflation that strips out volatile food and energy prices was 2.7%. The Fed targets 2% inflation over time.

Because officials don’t have much conviction over where the neutral rate sits, they are likely to be guided by how the economy performs in the months ahead. If inflation keeps slowing and the demand for workers looks soft, officials could conclude it makes sense to continue cutting rates along the path they envisioned in September.

If inflation progress stalls or ebullient financial markets raise concerns that inflation might get stuck above their target, officials might face more reservations around continuing to cut rates at a steady, meeting-after-meeting clip.

The most immediate focus is whether the Fed will cut again at its upcoming meeting in December. In September, 19 participants were about evenly divided over whether to cut rates one or two more times this year. Nine of them penciled in no more than one cut in either November or December, while 10 penciled in two cuts.

“The challenge is how do they signal whether or not they will move in December,” said Diane Swonk , chief U.S. economist at KPMG. “There’s a lot to learn between now and the December meeting. They can’t leave the door wide open, but they can’t close the door either.”

Even before the election result, recent data suggested that cutting again would be a finely balanced decision because inflation looks like it might end the year slightly above officials’ projection, while the unemployment rate has edged lower recently, said Matthew Luzzetti, chief U.S. economist at Deutsche Bank.

The election result— which sent stock markets to new highs while raising the prospect of stronger growth, higher inflation and better labor-market outcomes—boosted the odds that the Fed forgoes a cut next month, he said.

“Those could present a strong case from a risk-management perspective to potentially skip that meeting,” said Luzzetti.

In addition to juggling various assessments of how tariff increases or higher longer-term rates might alter the economic outlook, officials are grappling with an ongoing puzzle: The labor market has shown signs of cooling, with job postings falling, but consumer spending has been solid . It isn’t obvious how long these trends—steady consumption with a slowing labor market—can last.