GÖRLITZ, Germany—When the Cold War ended, European governments slashed their military budgets and spent a windfall of several trillion dollars on social welfare programs—a popular policy with voters when Europe faced few external threats and enjoyed the security protection of the U.S.

Now, European nations are finding it difficult to give up those peacetime benefits, even as the war in Ukraine has revived Cold War-era tensions and the U.S. tries to shift its focus to China . Most are failing to get their armies in fighting shape.

The lesson: It was easy to swap guns for butter; reversing the trend is far more challenging.

That means—despite promises to raise military spending —defense ministers say they are struggling to get what they need. In Germany, Europe’s largest economy, military bases are crumbling or have been converted to civilian use, including sports centers, old people’s homes and pension fund offices. The army, which numbered half a million in West Germany and 300,000 in East Germany during the Cold War, has today just 180,000. It now has a few hundred operational tanks, compared with more than 2,000 Leopard 2 main battle tanks its West German predecessor had in the late 1980s.

“That’s frustrating to me,” German Defense Minister Boris Pistorius told journalists recently, after getting much less than he had requested for next year’s military spending. “It means there are certain things I can’t do at the pace that…the level of threat requires.”

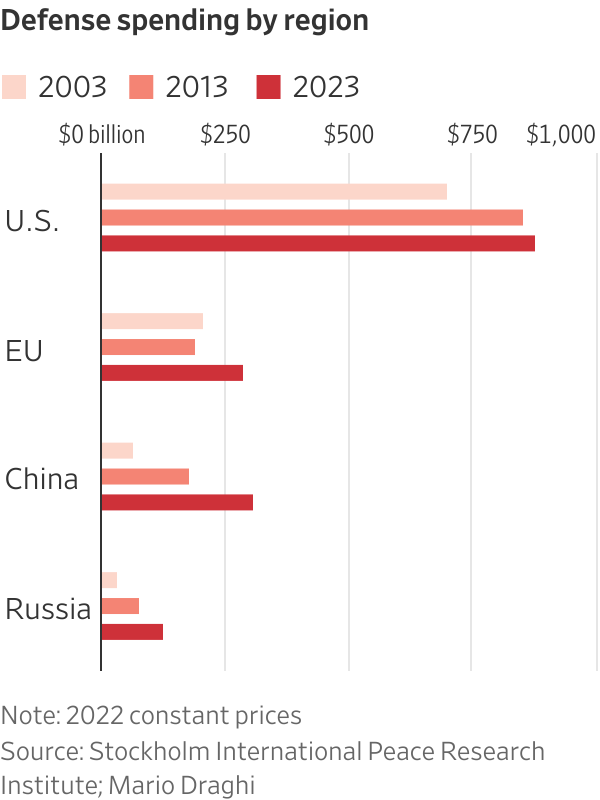

It is also likely to frustrate U.S. hopes that Europe will finally begin relieving some of the burden from Washington, which accounts for two-thirds of military spending among North Atlantic Treaty Organization allies. Both U.S. presidential candidates have said they want Europe to shoulder more of its security costs.

If Donald Trump wins in November, the call for Europe to do so would likely grow louder. Trump said in February the U.S. wouldn’t defend allies that don’t meet NATO’s minimum target of spending 2% of gross domestic product on their militaries, saying Russia could “do whatever the hell they want” with those that missed the target. In recent days, he said allies should be spending 3%—matching U.S. levels.

Few European nations, with the exception of Poland or the Baltic states , are close to spending 3% of GDP on their militaries. The U.K. had vowed, under the previous Conservative government, to raise military spending to 2.5% of GDP by 2030 from about 2.3%. But new Prime Minister Keir Starmer has refused to put a date on it. Military spending in Italy and Spain, meanwhile, sits under 1.5%.

At the current pace of rearmament, it would take Germany 100 years to return its artillery howitzer stockpiles to their 2004 levels, according to a report published earlier this month by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, an independent think tank.

Guns vs. butter

During negotiations for Germany’s 2025 budget earlier this year, Finance Minister Christian Lindner wanted to free up money for defense by freezing social spending for three years—letting it lag inflation. The move was rebuffed by other parties in the governing coalition, and the underlying defense budget was increased by just 1.2 billion euros, equivalent to around $1.3 billion, compared with 2024—just enough to cover the latest pay hike for military personnel. Spending on military aid for Ukraine was cut to €4 billion, about half this year’s level.

What the coalition parties did agree on was a €108-a-year increase over two years in Kindergeld—an annual €3,000 payment per child to all families, regardless of income. Today, that benefit alone, payable for offspring up to age 25, costs more than €50 billion a year, as much as Berlin’s annual Defense Ministry budget.

“The idea—we are dismantling the welfare state because we need more money for the military—I would find fatal,” said Economic Affairs Minister Robert Habeck .

Habeck argued that Germany not only faced an external threat from Russia, but an internal threat from people getting disillusioned with democracy—a jab at the ascendant far-right AfD party.

“Social spending is necessary to keep the country together,” said Habeck.

In the mid-1980s, West German military spending stood at around 3% of GDP and over 5% in East Germany. In 2022, the now-unified country spent around 1.4%. As a result, the country saved a total of €680 billion that was put toward rebuilding the formerly communist East and extending the welfare state there, according to Ifo, a Munich think tank. Europe as a whole has saved about €1.8 trillion since 1991 by spending less than 2% of GDP on its armed forces, Ifo calculates.

The meticulously restored town of Görlitz in Germany’s far southeast, a setting for Hollywood movies such as “The Grand Budapest Hotel” and “Inglourious Basterds,” shows the fruits of the country’s peace dividend.

In baroque town squares, pensioners sip flat whites. Students study free of charge at an airy, revamped university campus overlooking the river. The train station is being refurbished, a central square remodeled and the local hospital is building a new wing for the elderly.

The town also shows why politicians are leery of swapping butter for guns, economists’ term for the trade-offs states must make when choosing between military and social spending. With an elderly population and weak economy, the city receives the second highest regional transfers of taxpayer money in the form of subsidies and welfare benefits of any German district. Even so, spending pledges by the central government are straining the resources of Görlitz, which shoulders some of the costs, including support for children, said district administrator Stephan Meyer.

The district received a €40 million bailout late last year from the state government to cover a budget deficit. Meyer said he expects the gap between revenues and expenditures to grow to around €100 million by 2028.

“Everybody understands that we are at a very special juncture. The question is where will the money come from,” said Christian Mölling, a defense expert and director of the Europe program at the Bertelsmann Foundation in Berlin.

The turning point

Days after Russian President Vladimir Putin ’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz promised a “Zeitenwende,” or turning point. He pledged Berlin would raise military spending above 2% of GDP , and unveiled a special €100 billion off-budget investment fund for rearmament. Military experts welcomed the move, but warned the 2% threshold wasn’t enough to strengthen the military quickly given Germany’s chronic underspending.

Two years later, however, Germany’s underlying defense budget sits at 1.3% of GDP, and overall military spending is only meeting the 2% threshold thanks to the off-budget investment fund. When that runs out in 2028, Germany will have to hike its underlying defense budget by 60% that year to keep it above 2%—which analysts say is unlikely.

Not including the special fund, the share of the underlying defense budget that goes into procuring new weapons and ammunition has fallen from €10 billion in 2022 to €3 billion this year, according to Hans-Peter Bartels, president of the German Society for Security Policy, an armed forces lobby organization. The rest goes mainly to personnel, maintenance, training and building costs.

“The Zeitenwende has failed,” said Benjamin Tallis, a senior fellow at the German Council on Foreign Relations, calling the effort to rearm Germany “too little, too slow, too uncertain.”

Görlitz receives the second highest regional transfers of taxpayer money in the form of subsidies and welfare benefits of any German district.

The country’s public social safety net, meanwhile, totaled €1.25 trillion last year, an eye-popping 27% of GDP—higher than Denmark and Sweden and compared with around 23% for the U.S. in 2022, according to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Government officials counter by pointing to the rearmament fund and say strict budget rules mean Germany can’t borrow to spend more and cutting welfare risks endangering public support for Ukraine.

Unpopular with voters

Economists say there are many welfare measures that could be pared back to beef up military spending. A heavily subsidized €49-a-month ticket that gives access to public transport and regional trains nationwide costs the state €3 billion a year. Another €5 billion goes for training the unemployed despite an economy that is close to full employment, says Moritz Schularick, president of the Kiel Institute.

States such as Saxony, where Görlitz is located, offer additional perks, such as tens of thousands of dollars in subsidies for families who want to purchase their first home, and subsidized vacations for low-income families.

Raising Germany’s military spending to 3% of GDP would require finding an extra €40 billion a year, equivalent to France’s entire annual defense budget. A study by Mölling and colleagues published this month estimates that plugging the gap in Germany’s defenses by 2030 would cost €103 billion.

“I’m not sure [cutting welfare spending] is the solution,” said Michael Kretschmer , the conservative governor of Saxony, where Görlitz is located, saying the country needs to spend more on defense, but also on schools, infrastructures, and other items. “I think what we need is an economy that grows faster.”

The far-right AfD party has performed well in state elections in East Germany, in part by opposing more military spending. Photo: Yen Duong for WSJ

Upstart political parties, such as the AfD, have been betting that there is little appetite among the public for increasing military spending. The party won the eastern German state of Thuringia and almost won in Saxony state elections on Sept. 1—in part by pledging new benefits such as free school meals, while promising to seek reductions in military spending.

“Ukraine and refugees are more important than school food?” said Mike Moncsek, an AfD member of the German Parliament from Saxony.

The new far left BSW party also scored well in the election by promising butter over guns. “We don’t want to prepare for war, we want to prepare for peace,” said Zaklin Nastic, the party’s defense policy expert in parliament. “And above all, we need to preserve social peace here in Germany.”

Meanwhile, military projects have faced local opposition. Last summer, not far from Görlitz, hundreds of protesters and local politicians from the far right and far left protested close to a disused air base where Manfred von Richthofen, the World War I flying ace known as the Red Baron , once trained.

The protesters wanted to block the country’s leading arms manufacturer, Rheinmetall , from building a new ammunition factory on the site that would supply Ukraine and restock German stockpiles. Many feared the factory could become a target of Russia. Within weeks, the company said it would add capacity to an existing plant in Bavaria instead.

North of the city lies one of the largest military training grounds in Germany. Görlitz Mayor Octavian Ursu would like to expand the facility, but local politicians are opposing the move.

“Residents complain that too much is being done for Ukraine,” Ursu said.

Write to Tom Fairless at tom.fairless@wsj.com and Bertrand Benoit at bertrand.benoit@wsj.com