LISBON—The Americans are here, and this sun-bleached coastal city is booming.

At bars, hotels and restaurants that line winding cobblestone streets, business is so good that Mayor Carlos Moedas recently slashed local income tax for residents. With economic growth of 8.2% last year and a 20% rise in tax revenue from prepandemic times, he’s also made public transportation free for young people and the elderly.

Centuries-old facades are being polished up after years of neglect. Planning is under way for a new airport, twice the size of the existing one, and for a three-hour high-speed rail link to Madrid in neighboring Spain. The Tribeca Film Festival will come to town this fall.

Room rates in the city are rising, and tourism investment is flooding in. Gonçalo Dias, director and co-owner of the Ivens, a $1,000-a-night hotel in downtown Lisbon, said he plans to add a jazz club in the basement. More than half of his room reservations come from Americans.

“Great times. The best times for the last 45 years,” he said. “It’s crazy.”

A Mediterranean rush

Across southern Europe, an unprecedented tourism boom driven largely by American tourists is turbocharging growth in places that had become bywords for economic stagnation, creating hundreds of thousands of jobs and filling the coffers of governments recently shaken by sovereign debt fears.

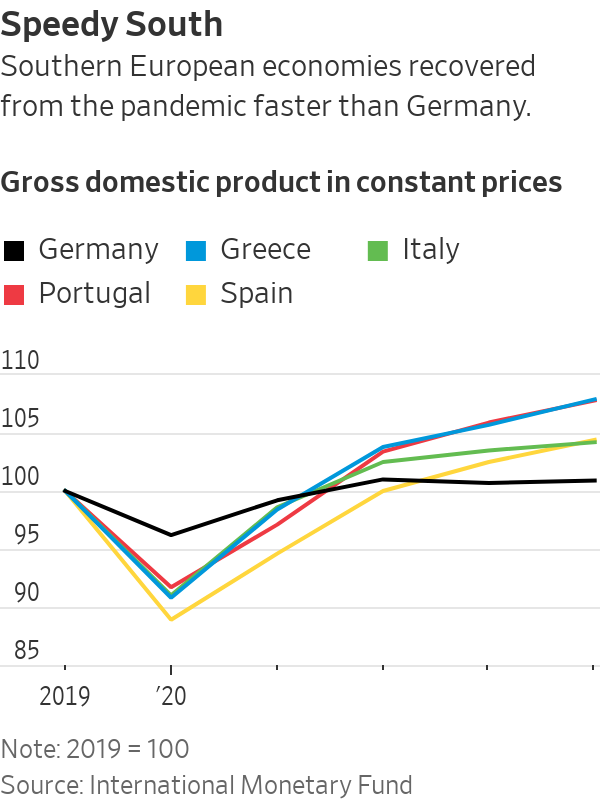

Even as some worry the boom may be creating other problems, the Mediterranean rush is turning Europe’s recent economic history on its head . In the 2010s, Germany and other manufacturing-heavy economies helped drag the continent out of its debt crisis thanks to strong exports of cars and capital goods, especially to China.

Today, Italy, Spain, Greece and Portugal contribute between a quarter and half of the bloc’s annual growth.

While Germany’s economy is flatlining , Spain is Europe’s fastest-growing big economy. Nearly three-quarters of the country’s recent growth and one in four new jobs are linked to tourism. In Greece, an unlikely economic star since the pandemic, as many as 44% of all jobs are connected to tourism.

The short term is bright, and governments are pushing to build on that momentum. But some economists, residents and politicians are concerned about the boom’s long-term implications.

Rent and other living expenses are rising in hot spots, making it harder for many locals to make ends meet. A heightened focus on tourism, which turns a quick profit but remains a low-productivity activity, tethers these economies to a highly cyclical industry. It also risks keeping workers and capital from more profitable areas, like tech and high-end manufacturing.

Can Europe’s emerging “museum economy” support sustained wealth creation and the expansive welfare systems Europeans have become accustomed to since the end of World War II? And what happens if the dollar falls and the tourists leave?

The new economic engine

In Portugal, a country of 10 million that juts out into the North Atlantic from Spain, Americans recently surpassed Spaniards as the biggest group of foreign tourists.

“It is literally, for Americans right now, the place to go,” said Ameshia Cross, a political strategist from Washington, D.C., visiting Portugal for the first time.

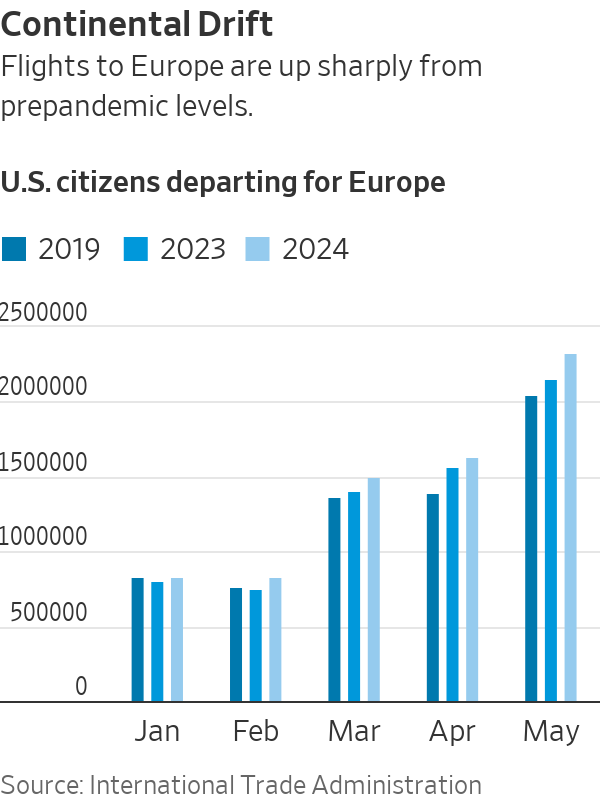

The strong dollar—and a powerful post-Covid recovery—has empowered millions of Americans who would have vacationed in the U.S. before the pandemic. They are now finding they can afford a lavish European holiday .

“Your dollar goes a lot further,” Cross said over coffee in the lobby of her five-star hotel. “You don’t feel you’re scrounging as much.”

On her six-day trip, Cross picked up cheap tickets to see Taylor Swift in concert —also the singer’s first visit to Portugal—and shopped for clothes on the tony Avenida da Liberdade. One of her friends happened to be in Lisbon at the same time, she said. More friends were coming in two weeks, and another group in September.

Tourism now generates one-fifth of economic output in Lisbon and supports one in four jobs. That boom has reverberated far beyond the capital.

Portugal’s gross domestic product grew nearly 8% between 2019 and 2024, compared with less than 1% for Germany, according to International Monetary Fund estimates. The government recorded a rare 1.2% of GDP budget surplus last year, and its debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to fall to 95% this year, the lowest since 2009. Portugal’s population is growing again after years of decline, thanks in part to an influx of migrant workers and to various tax incentives and investor visas that have attracted high-income workers.

Moedas, Lisbon’s mayor, says there’s room for further growth. For a city that doubles in size to around one million every day, including commuters, only around 35,000 are tourists, he said. “We are very far from a situation of so-called overtourism.”

How an economic crisis paved the way

The trend is part of a global readjustment following the Covid-19 lockdowns. Spending on travel and hospitality worldwide grew roughly seven times faster than the global economy over the past two years, according to Oxford Economics. That pattern is expected to continue for the next decade, though to a lesser degree.

Europe, especially southern Europe, has benefited more than many other regions. Though it is home to just 5% of the world’s population, the European Union received around one-third of all international tourist dollars—more than half a trillion dollars—last year. This is up roughly threefold over two decades, and compares with about $150 billion for the U.S., where tourism has been slower to rebound.

One reason is the brutal sovereign debt crisis that hit the continent’s south especially hard just over a decade ago. Unable to stimulate demand with public spending or to energize exports by devaluing their currency—the euro, which is shared by 20 states—those countries could only boost their competitiveness by lowering wages. This and a real estate collapse that left hundreds of thousands of workers suddenly available made the region’s tourist industry ultracompetitive, much cheaper than Caribbean beach destinations and on a par with Latin American destinations like Mexico.

For Portugal, there was another, little-known reason the eurozone debt crisis turned out to be an unexpected boon.

When the country was rescued with a €78 billion bailout in 2011, around $115.5 billion at the time—the final indignity at the end of a decadelong economic downturn —one way the government agreed to raise money in return was by privatizing TAP Air Portugal , the struggling national airline. It sold a controlling stake to a consortium formed by JetBlue founder David Neeleman .

“I was born in Brazil, speak Portuguese, but had never been to Portugal myself,” Neeleman said. “I didn’t know anyone who had been to Portugal…. It was so inconvenient that people didn’t do it.”

Once an owner of TAP, Neeleman increased the number of direct flights to the U.S. eightfold between 2015 and 2020, adding major hubs such as JFK and Boston Logan, betting that would open up an untapped market. As bookings soared, other U.S. airlines followed.

“It was actually comical, because I went from knowing no one who had been to Portugal to everyone telling me they were going to Portugal,” said Neeleman.

Moedas, the mayor, said: “I don’t think people at the time realized how important it was.”

Signs of discontent

For Gonçalo Hall, a 36-year-old tech worker, the influx of foreign cash that has transformed Lisbon has been overwhelmingly beneficial for the city. When he lived in the capital 15 years ago, he wouldn’t walk in the historic downtown after 8 p.m. It was “full of homeless people, not safe. Lots of empty and abandoned buildings,” he said.

Even so, the boom has had downsides for him and other locals—the most immediate of which is the rise in living costs.

“The quality of life in Lisbon doesn’t match the prices. Even expats are leaving,” said Hall, who moved to the Atlantic island of Madeira during the pandemic and continues to work remotely.

The average Portuguese employee earns around €1,000 a month after tax, or around $1,100 a month, and only 2% earn more than €2,000. A one-bedroom apartment in Lisbon can easily cost more than €500,000 to buy, or over €1,200 a month to rent. Rents in nearby cities are also climbing as people leave the capital, squeezed out as lucrative short-term rentals transform the housing market.

Jessica Ribeiro, a 35-year-old sociologist, pays around €490 a month for an apartment that she shares with her ex-husband in a town close to Lisbon. Neither can afford to leave. Both make a little more than the minimum wage of €820 a month, and soaring rents mean it is impossible to find an apartment in the neighborhood for less than €700, Ribeiro said.

“The harm that tourism has brought is infinitely bigger than the benefits,” Ribeiro said. “It sends people away from their place of work, making their lives much harder.”

A frequent complaint from residents and housing advocates is that some of the boom’s biggest winners are American companies, from Airbnb to Uber , which often pay little tax in the places where they do most of their business.

Lisbon is cracking down on Airbnbs and increasing taxes on tourists, doubling the nightly city tax from €2 to €4, which should raise €80 million a year. Airbnb has paid Lisbon and Porto, Portugal’s two biggest cities, more than €63 million after entering into voluntary tax collection agreements with local officials. Moedas said he is considering “a bit more regulation” of the city’s many Ubers, whose drivers he said don’t always respect traffic rules.

An Uber spokesperson said most of the revenue generated by the platform stays in the local economy, and the company last year helped drivers, couriers and restaurants in Portugal earn more than €500 million. All Uber drivers in the country are required to be licensed by a state agency, the spokesperson said.

Around nine in 10 Airbnb hosts in Portugal rent their family home and almost half say the extra income helps them afford to stay in their homes, according to a spokesperson for the company. “Guests using our platform account for just 10% of total nights booked in Portugal, and we follow the rules and only allow listings that are registered with local authorities,” the spokesperson said.

For many residents, the government’s remedies don’t go far enough. “All the city is subordinated to tourism,” said Rita Silva, a housing campaigner and researcher.

Higher rents are forcing many businesses and cultural and social spaces catering to locals to close, according to Silva. “This is not an economy that is serving the needs of the majority of people,” she said.

Signs of discontent are bubbling up across the region. Tens of thousands of local residents marched in Spain’s Balearic and Canary islands in recent months to protest mass tourism and overcrowding. On Mallorca, activists have put up fake signs at some popular beaches warning in English of the risk of falling rocks or dangerous jellyfish to deter tourists, according to social-media posts.

‘Beach disease’

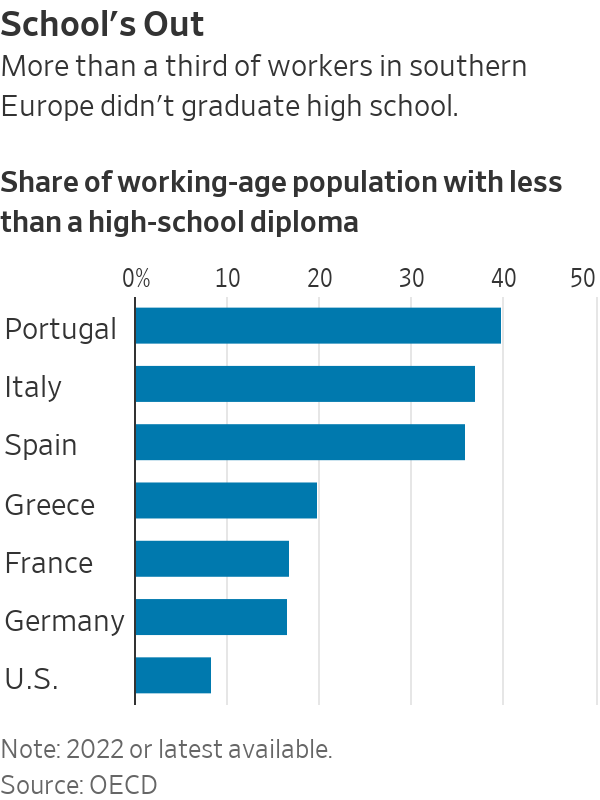

Some economists and others worry swelling tourism might be aggravating Europe’s existing economic challenges.

Serving foreigners is difficult to scale up and is more exposed to economic headwinds. Like the discovery of oil, southern Europe’s new focus on tourism can crowd out higher-value activities by hogging capital and workers, a phenomenon some economists have dubbed the “beach disease.”

“Portugal isn’t an industrialized country. It’s just the playground of the EU,” said Priscila Valadão, a 43-year-old administrative assistant in Lisbon. She makes €905 a month and rents a room from a friend for €250 a month. “The type of jobs being offered…are restricted to a type of activity that really doesn’t enrich the country,” Valadão said.

For Europe’s policymakers, having people open hotels or restaurants is easier than incentivizing them to build up advanced manufacturing, which is capital intensive and takes a long time to pay off, said Marcos Carias, an economist with French insurer Coface .

“Tourism is the easy way out,” Carias said. “What is the incentive to look for ingenuity and go through the pain of creating new economic value if tourism works as a short-term solution?”

Proponents say tourism attracts capital to poor regions, and can serve as a base to build a more diversified economy. Lisbon’s Moedas said he is trying to leverage the influx of foreign visitors to build up sectors such as culture and technology, including by developing conferences and cultural events.

“Some extreme left parties basically say we need to reduce tourism,” Moedas said, but that is the wrong approach. “What we have to do is to increase other sectors like innovation, technology…. We should still invest in tourism, but we should go up the ladder.”

In Athens, Mayor Haris Doukas says he is working on extending the tourist season, increasing the average length of stay and promoting specific types of tourism, such as organizing conferences and business meetings, to attract visitors with higher purchasing power. He’s also called for new taxes to help the city accommodate the millions of additional tourists thronging to the ancient capital.

Workforce woes and booming business

One symptom of “beach disease”: Higher living costs and a lack of high-wage jobs are encouraging more Portuguese students to leave the country, said Arlindo Ferreira, a school principal in northern Portugal.

Schools are also struggling to recruit teachers, “not only because of the living costs but also [they] can get better salaries in other areas,” Ferreira said.

More than one-third of highly qualified Portuguese students leave the country after graduating, according to Raquel Varela, a labor historian and professor at New University of Lisbon. Even higher-paid technology workers have started decamping to cheaper places.

Tiago Araújo, chief executive of tourism tech startup HiJiffy, has held on to his employees but says many of them have been moving out of Lisbon. The trend, which started during Covid, is now being primarily driven by the housing crisis.

Still, the tourism boom has helped Araújo’s company. Hotels now have extra resources to invest in HiJiffy products, including a Facebook messenger chatbot that allows guests to book rooms directly rather than through big online platforms that charge hefty commissions.

For many beneficiaries of the boom, the lure of free-spending Americans who have helped bring about this transformation is just too attractive.

While Dias, the hotel owner, is diversifying into nightlife, he refuses to envisage a future where the sector would have to rely heavily on visitors from elsewhere.

If Americans stop coming to Lisbon, he said, “I don’t think we can charge this kind of [price] because we will have to go to Europeans, and the Europeans, they don’t have money.”

—Patricia Kowsmann contributed to this article.

Write to Tom Fairless at tom.fairless@wsj.com