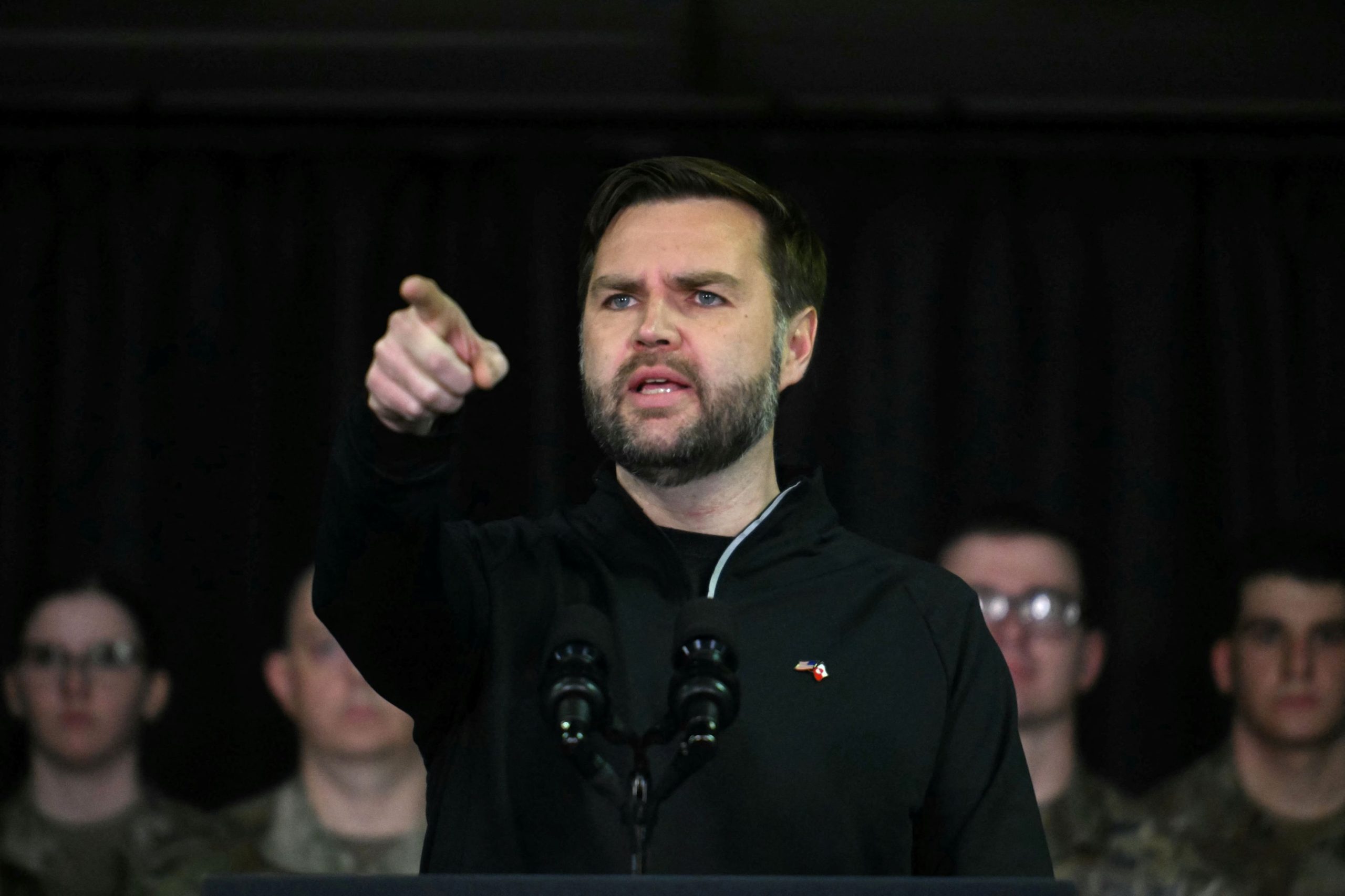

European leaders had hoped that Vice President JD Vance ’s antagonism was a political show to build domestic support. Now, after Vance expressed disdain for Europe in a private text chat about Yemen attack details, officials are coming to terms with a vocal vice president whose antipathy for Europe appears to run deep.

“I just hate bailing Europe out again,” he said regarding planned U.S. strikes against Houthi rebels, in an exchange published by the Atlantic magazine. He told fellow administration officials that the U.S. was “making a mistake” by hitting the Houthis, whose attacks on Red Sea shipping have scrambled global shipping routes.

He noted that only “3 percent of US trade runs through the Suez. 40 percent of European trade does.” Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth replied to Vance’s comments: “I fully share your loathing of European free-loading. It’s PATHETIC.”

Vance has played a leading role in sharpening tensions between Washington and Europe, articulating a degree of contempt for the Continent that transcends President Trump ’s milder scorn. He lambasted European democracies in a speech in Munich last month, calling European Union officials “commissars.” He once called Ukraine “a country I don’t care about.” In the Oval Office recently, he berated Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in front of Trump and international media.

People close to Vance said his stance comes from a desire to bolster Europe with U.S. interests in mind.

“It might look bad from the outside, but what you’re doing is having the tough talks you need to be strong,” said Rep. Brian Mast (R., Fla.), chairman of the House Foreign Relations Committee and a friend of the vice president. He said both he and Vance, who served in the military, have “some level of a chip on the shoulder” because Europe hasn’t been pulling its weight on security, though it has begun to thanks to pressure from the administration. “What we need from Europe is a Europe that doesn’t need America,” Mast said.

Another close friend and informal Vance adviser, Cliff Sims, said the vice president “has a fully formed worldview that is clearly thought out. These are sincerely held beliefs. A lot of Europeans get mad at his comments but they can’t refute the underlying substance.”

Most European leaders have remained quiet about Vance’s disdainful comments, but a few have spoken out.

Partners should show “more respect and consideration” than Vance has, said Bruno Fuchs, chairman of the foreign relations committee in France’s National Assembly. Otherwise, he said, the administration should “express clearly that the historic relationship between the United States and Europe has evolved to the point that Europe is no longer a privileged partner of the United States.”

Vance hasn’t shied away from ruffling feathers. After the White House on Sunday announced a visit to Greenland this week by Vance’s wife and senior administration officials that sparked ire in Denmark, Vance on Tuesday said he would join the entourage, further angering Danes.

“There was so much excitement around Usha’s visit to Greenland this Friday that I decided that I didn’t want her to have all that fun by herself,” Vance said of his wife in a video posted to X . The White House later said the visit would just be to a U.S. military base on the island.

A former U.S. senator who holds a law degree from Yale University, Vance cites data on Europe’s economy and military to illustrate its poor performance and reliance on the U.S. He mixes that with strong opinions, like that Europe is more endangered by “the threat from within”—which he described as a retreat from fundamental values such as freedom of speech—than from Russia.

While Europeans have long faced ridicule and criticism from the U.S. for red tape, short working hours and weak militaries, among other issues, Vance’s venomous comments are unprecedented from such a high-level official.

A growing concern among people in the U.S. and Europe who value the trans-Atlantic relationship is that if Vance’s views gain traction in White House policymaking, America’s deepest and most valuable international relationship will risk profound harm.

Vance, who spent five years as a venture capitalist, including working with tech entrepreneurs in the Bay Area, echoes views on Europe aired by other Trump-allied tech leaders. Prominent among them is Elon Musk , who is now a senior administration official. Musk, like Vance, has criticized Europe for punishing views that he considers free speech and slammed Europe’s openness to migrants.

For now, Vance is the loudest voice in one faction of Trump’s inner circle. It remains unclear how much influence he has on the president, who has a record of playing off those around him against each other.

During Trump’s first term, people around the president worked to maintain calm, said Gabrielius Landsbergis , who was until recently Lithuania’s foreign minister. Now it seems his advisers are fanning volatility, he said.

Officials who support disengagement from Europe, including Vance, “are using Trump as a cannon to level the trans-Atlantic bridges,” Landsbergis said. “If it is ideological, then all of us just need to prepare for a post-American world in Europe.”

Trump hasn’t been gentle with Europe, either. He has browbeaten Europeans for freeloading on American support, placed tariffs on European products and threatened to pull the U.S. from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Yet European officials have still believed they could work toward some kind of transactional accommodation with him.

Vance has Europeans flabbergasted because his approach seems to be driven by a fundamental dislike of the way European democracies work. His public animus is even more confounding because many European officials have found him friendly, supportive and positive in private conversations. One senior European official who first met him a few years ago said one could agree to disagree with Vance over Ukraine and other issues but still have a useful conversation.

Europeans first grasped Vance’s antagonism during a speech last month at the Munich Security Conference, in which he lambasted the Continent for abandoning Western values.

“You could feel the hatred emanating from him,” said Alina Polyakova, president of the Center for European Policy Analysis, a Washington-based think tank. Polyakova, who was in the auditorium during Vance’s address, said his approach is much more dangerous for Europe than that of Trump, who tends to view politics as similar to contract negotiations, with little emotion.

“Vance is emotional about his hatred for Europe. It’s hard to break through that,” said Polyakova.

When the Trump team took office, European leaders had hoped they could work with Vance, a bestselling author whom many had met over recent years. Days after the inauguration and before the Munich conference in mid-February, Germany’s top politician spoke optimistically about a planned conversation with Vance at the event.

“I’m looking forward to meeting him,” Friedrich Merz told The Wall Street Journal shortly before winning elections that have made him chancellor-designate. “I read his book five or six years ago. I didn’t expect that I would one day meet this author in his role as vice president of the U.S.”

After the conference, one official close to Merz said the dominant feeling was confusion. Vance’s speech had excoriated Europe’s mainstream parties for not bringing far-right forces into government and hinting that U.S. military protection for the region could be withdrawn if they persisted.

But in a private meeting with the German conservative leader, the official said, Vance was all smiles despite Merz’s categorical refusal to form a government with the far-right Alternative for Germany, which Vance has supported.

Write to Daniel Michaels at Dan.Michaels@wsj.com , Laurence Norman at laurence.norman@wsj.com and Matthew Dalton at Matthew.Dalton@wsj.com