At the annual convention of the International Longshoremen’s Association last year, two large screens played a TikTok video from a crane operator over the docks of Los Angeles.

“Aaaall of this, man, is all automated,” he said, pointing toward acres of stacked containers stretching to the Pacific. He marveled at the automated vehicles driving amid the containers: “No drivers in any of those machines…. They’re no joke, man.”

From the podium, Harold Daggett , the union’s pugnacious leader, was having none of it. “They say that’s the future,” he bellowed to the thousands of gathered workers. “Over my dead body.”

Tens of thousands of dockworkers last week returned to their jobs on East Coast ports after a three-day strike that threatened to snarl trade and hobble the economy. Workers won a 62% pay increase. But a much larger, thornier issue remains—one that’s playing out in other businesses as well, from factories to grocery stores to Hollywood: How much, and how quickly, are humans willing to concede to machines?

The new dockworker agreement extends only until mid-January. Daggett’s opposition to automation of any kind threatens to derail the continuing negotiations over the next three months and push the dockworkers back to the picket lines.

The long march of technological advancement has transformed manufacturing and countless industries over the decades—and brought attempts to defy change. Workers in a range of industries today fear being displaced by ever-more sophisticated machines, particularly with the rapid rise of artificial intelligence.

“Someone has to get into Congress and say, ‘Whoa, time out,’” Daggett said in a recent video interview. “What good is it if you’re going to put people out of work?”

Shipping executives note with frustration that U.S. ports lag behind facilities in Europe and Asia in automation. Major Asian and European ports consistently rank higher than their U.S. counterparts in an annual ranking by the World Bank that measures factors such as port productivity and the amount of time a ship spends in port.

One issue of contention is the effect of adapting automation on jobs. Employers say it creates new jobs as automation requires new roles and drives more cargo through ports. Unions point to roles lost to machines—a dockworker, for instance, might not be equipped to slot into a new job that requires specialized or high-tech skills.

It’s challenging to quantify the impact. Many factors impact the amount of work at any given terminal, including the size and frequency of ships arriving and departing.

Across all industries, Daron Acemoglu , an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, estimates that around six jobs are lost for every robot implemented. About 700,000 American jobs—many of them in manufacturing and other blue-collar trades—have been lost over the past 30 years due to automation, he said.

For dockworkers and others, “the real issue is what does this look like five years, 10 years into the future?” said Timothy Bartl, CEO of the HR Policy Association, a trade group representing chief human-resources executives. “How do we start anticipating that?”

More cargo

Shipping industry officials say they need machines, like automated stacking cranes powered by artificial intelligence, to squeeze ever-growing volumes of cargo through ports hemmed in by sprawling metropolitan areas. Some of the world’s most efficient ports, such as Khalifa Port in Abu Dhabi, are built on greenfield or offshore sites where space is abundant.

The U.S. already boasts some advanced cargo-handling operations. In sections of ports around the country, automated cranes lift massive containers from ships, autonomous vehicles carry boxes across the docks, and yet more autonomous cranes organize giant container stacks. Cameras and computer systems read codes on containers and truck trailers to automatically allow trucks into and out of ports and to track and speed the flow of cargo.

Automation drives predictability and consistency. Machines don’t call in sick, stop to chat in the parking lot with friends or text friends and family members during work hours. But they can’t solve everything. The supply-chain snarls during the Covid pandemic that led more than 100 containerships to back up off the coast of Long Beach and Los Angeles were caused as much by shortages of warehouse space, trucking equipment and railcars as they were by inefficiencies on the docks.

Still, the sole fully automated terminal at Long Beach worked ships and managed container stacks better than all of its peers in the pandemic. Now shipping companies are looking to add autonomous cranes and vehicles to terminals large enough to accommodate them. In terminals too small or awkwardly shaped to deploy robots, they’re aiming to make better use of cameras, artificial intelligence and other technologies.

The ILA and its West Coast counterpart, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, are opposing, stalling and drawing out expensive concessions from employers in return for allowing the technology.

Total Terminals International at the Port of Long Beach recently negotiated a deal with the West Coast union to install automated technologies. The details are still being worked out but are likely to include taller cranes that will be operated from a remote room and automated stacking cranes on the docks, said Ammar Kanaan , the chief executive of the terminal’s owner.

Kanaan said the total number of jobs at the terminal won’t be cut, but the mix of jobs will change. He said the improvements will allow the terminal to move twice as much cargo without expanding the facility.

Some in the shipping industry are concerned the company made costly commitments to the union on staffing requirements, according to one industry official. Dockworkers, meanwhile, are worried that the West Coast union is allowing automation at too many terminals, the official said: “The East Coast has seen what has happened on the West Coast and they want to prevent that from happening.”

The East Coast union says the Los Angeles automation project beamed into the ILA convention cost hundreds of dockworker jobs. The company that owns the terminal, Denmark-based shipping giant A.P. Moller-Maersk , declined to comment. But the West Coast employer group that represents companies like Maersk said the number of longshore workers at the Los Angeles and Long Beach ports where automation is increasingly used employed 13% more dockworkers last year than five years earlier.

The human impact

On the East Coast, the ILA’s labor contracts usually include language requiring employers to seek union approval for use of automation at existing port facilities. According to one shipping industry official, the tentative salary deal that would raise dockworker pay to $63 an hour from $39 an hour was reached on the condition that dockworkers agree to efficiency gains that include more technology.

Marc Santoro remembers the anxiety he felt when his terminal at Bayonne, one of the smallest at the Port of New York and New Jersey, installed automated dockyard cranes 10 years ago. Santoro, 44 years old, said the employer gave the impression the cranes would handle larger volumes of cargo and therefore create more work. What happened, he said, was 30 people who used to operate in shifts working 20 cranes became four people working in a room.

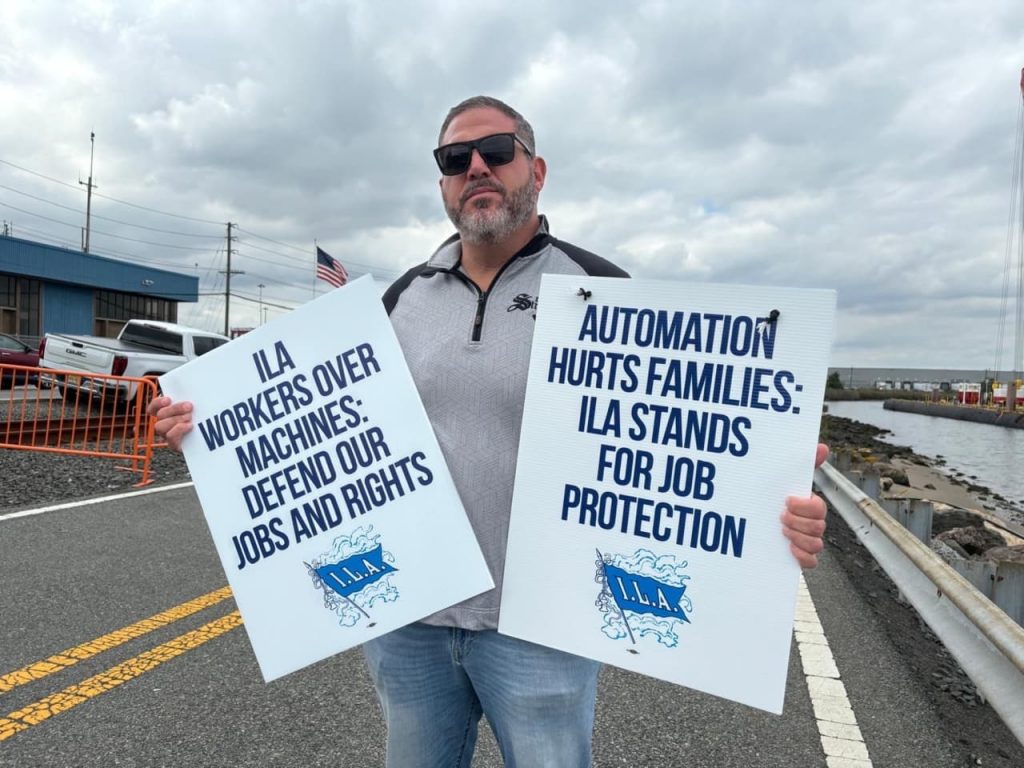

Santoro, a father of three who was on the picket lines outside Port Liberty last week, said people may not have been laid off as a direct result, but the restructuring was felt by crane operators like him immediately. He rushed to call other terminals to pick up new shifts, but “it definitely didn’t make up for the lack of work,” he said.

“Automation impacts humans and Americans,” he said. “If you have kids, you should be concerned about automation.”

At the Port of New York and New Jersey, the largest port on the East Coast, the number of licensed dockworkers in 2020 was virtually unchanged from a decade earlier at just over 5,800 workers, according to the port’s regulator.

Shipping industry officials say that more efficient cargo operations lead to more cargo, which requires more dockworkers to load and unload ships. Machinery requires more mechanics and highly skilled employees who can oversee, upgrade and fix computers and robots.

An executive at CMA CGM, the French ocean shipping company that bought the Port Liberty terminal two years ago, has said beefed-up automation will help the facility double its capacity so that it can move more than four million boxes annually over the coming years.

Daggett said he wants to take his fight worldwide. He has talked in recent months about joining with unions around the world to punish ocean shipping companies that push automation by temporarily refusing to work their ships.

“I don’t care about lawyers and governments,” he said. “It’s time to stop machines from taking our jobs, destroying our lives and crippling the American economy. It’s time we put companies out of business that push automation.”

Lessons from Germany

Over the past century, machines have upended many industries. In the U.S., robots have been used on automotive assembly lines since at least the early 1960s, with carmakers turning to automation to increase productivity, cut labor costs and reduce injuries, particularly on repetitive tasks. Robots took on the difficult work of lifting, welding and painting cars. Today, the auto industry is a top consumer of robots around the world.

Automation has also eliminated the need for many clerical workers and bookkeepers in corporate functions. Breakthroughs in artificial intelligence now threaten the jobs of even highly skilled professionals, such as software developers.

To lessen the pain for workers, the U.S. may be able to draw lessons from how German firms incorporated automation and technology, MIT’s Acemoglu said. There, unions and worker councils represent the workforce and advocate for technological changes and training programs that can allow employees to take on new jobs within the same organization. “The ILA saying no to robots is never going to work,” he said.

The challenge for workers is how to adapt, said Michael Chui , a partner at the McKinsey Global Institute, the research arm of the consulting firm.

“It’s very rare that a machine will come in and do everything that’s in someone’s occupation,” Chui said. “Typically, what we see is automation doing pieces of people’s jobs. It’s less about, ‘In comes the robot and out goes the person.’”

Proponents point to technology’s safety benefits. Dockworkers work long hours, sometimes around the clock, in heat and cold and rain, and around large containers, vehicles and cranes. Automation allows them to work in the comfort and relative safety of a climate-controlled office.

Many see efforts to hold off advances in technology as ultimately doomed to fail.

“Ever since the Luddites, it’s been pretty hard for workers to really slow down automation over the longer term,” said Harry Holzer, an economist at Georgetown University. “Unions can slow it down a bit, but really, not very much, and not for very long.

Write to Paul Berger at paul.berger@wsj.com , Chip Cutter at chip.cutter@wsj.com and Chao Deng at chao.deng@wsj.com