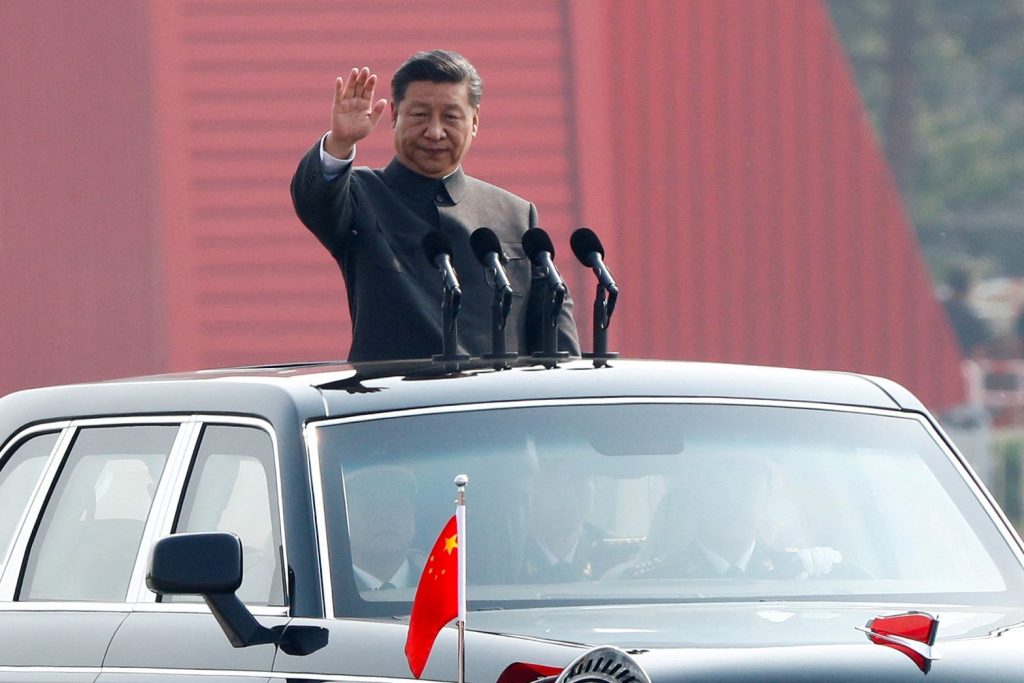

Chinese rulers have long used campaigns against corruption to sideline rivals and consolidate power. Xi Jinping is increasingly tying his authority to a new variation: a purge that never ends.

With echoes of Mao Zedong’s “continuous revolution,” Xi has sent fear rippling through the ranks of the Communist Party for more than a decade with the largest campaign against corruption in modern Chinese history. It is now threatening to petrify the party as it tries to steer the world’s second-largest economy through its greatest period of uncertainty in a generation.

Since he came to power in 2012, party enforcers have punished roughly five million people for offenses as serious as abuse of power and as innocuous as creating excessive red tape.

In 2023 alone, the unrelenting campaign swept through the worlds of finance, food, healthcare, semiconductors and sports—taking down scores of senior officials, bankers, hospital directors and even soccer administrators. China’s foreign and defense ministers went missing in the summer before being abruptly removed from their posts, leading to suspicions that they, too, have been purged. Beijing’s recent ouster of a dozen senior military and defense-industry officials from the national legislature and a government advisory body have fueled speculation about a broader shake-up of the country’s military establishment.

There is no end in sight. The Chinese leader recently outlined his plans for how the campaign would proceed in the next few years and has even targeted the very agency tasked with carrying it out.

Critics of Xi say the campaign’s extension into a second decade is a result of his refusal to accept structural changes and greater transparency that are necessary for cleaner governance.

The Chinese leader has instead cast the blame on the moral failings of individuals, while doubling down on his centralized and opaque style of governance, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of Xi’s remarks, party directives and official data. Only a continual cleansing can ensure the party remains potent and pure, he has argued.

“Battling corruption is the most thorough form of self-revolution,” Xi said days before starting his third term as party chief in October 2022. “As long as the soil and conditions conducive for corruption continue to exist, the fight against corruption can’t cease for a moment.”

Such an assertion clears the way for Xi to use disciplinary purges indefinitely as a way to enforce fealty, through fear, to himself and his vision.

“In China, campaigns are supposed to be an intense but short burst of enforcement,” said Yuen Yuen Ang, a political-science professor at Johns Hopkins University. “Xi has invented a paradoxical policy tool: a perpetual campaign.”

While the forever purge buttresses Xi’s authority, it also has instilled a constant apprehension and reluctance to act decisively among party members as challenges mount. The economy is struggling to shake its Covid hangover. Youth unemployment has skyrocketed, and the property market and consumer sentiment have tanked. Meanwhile, debt is piling up and foreign investors are increasingly turning their backs on the Chinese market.

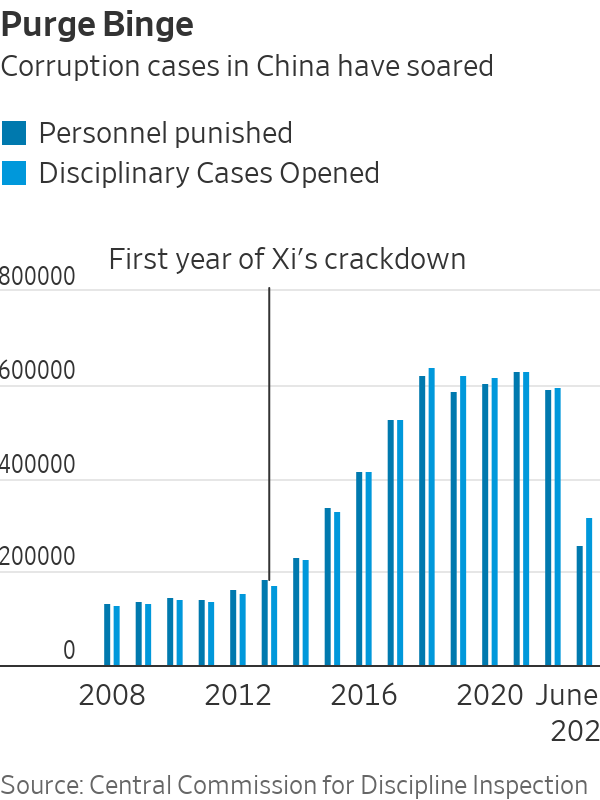

In the early years of the campaign, many officials saw it as a longer and more ambitious version of previous efforts. Roughly 180,000 people were disciplined for infractions in 2013, a number that climbed to some 621,000 in 2018, the year Xi proclaimed a “crushing victory” over corruption.

Official data show at least half a million people being disciplined every year since 2017—around four times as many as were typically punished annually when Xi’s predecessor held power from 2002 to 2012.

By some measures, corruption has indeed fallen under Xi. Berlin-based advocacy group Transparency International ranked China 65th in its 2022 index on perceptions of public-sector corruption in 180 countries and territories, an improvement from 80th out of 176 jurisdictions in 2012, the year Xi took power.

A survey published in 2020 by Harvard University’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation found that the proportion of Chinese citizens who saw officials as being generally “clean” rose to more than 65% in 2016 from roughly 35% in 2011.

There are other indications, however, that Xi hasn’t curbed corruption so much as pushed it deeper into the shadows. The new five-year plan for fighting graft released in September pledges to curb new and hidden forms of corruption where officials use murky corporate structures and “revolving doors” between the public and private sectors to seek illicit gains.

A recent case involving Zhang Jing, a former local official in southwestern China, shows corruption has remained insidious and persistent. Zhang’s offenses date to the early 2000s, when as a township party chief, he started accepting “red envelopes” of cash from entrepreneurs and friends in return for providing inside information about government projects, according to an official account.

When one of those entrepreneurs was detained by authorities in 2013, Zhang grew frightened, to the point of asking a feng shui master to pray for his safety, according to the account. He tried to cover his tracks, such as by returning a bribe to one entrepreneur through a bank transfer—so that he could cite bank records to plead innocence—before taking the bribe again in cash later.

Authorities didn’t catch up with Zhang until 2022, when the party detained and eventually expelled him. In March 2023, he was sentenced to four years in jail after being found to have taken more than 1.24 million yuan worth of bribes, equivalent to around $175,000 at current rates.

“I didn’t pull back from the precipice and confess to the organization in time,” he said in his confession. “Instead I racked my brains to try to cover up my crimes.”

Investigations involving more visible forms of corruption have fallen in recent years, according to official data. People punished for dining on public money dropped to around 9,300 in 2022 from 13,600 in 2018, and those disciplined for holding lavish events such as weddings and banquets slipped below 3,000 from 7,000 over the same period.

Meanwhile, the number of people disciplined for improper giving and receiving of gifts—a more hidden form of graft—have steadily climbed, rising to 23,000 in 2022 from about 6,800 in 2015.

The party’s top internal watchdog, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, has warned about a growing trend of “options corruption”—named after a type of financial contract—whereby crooked cadres provide favors in return for deferred bribes to be paid out only after they retire, as away to mask their misconduct.

Despite his efforts to fight graft, which include cutting government approvals and red tape that officials can abuse to extract bribes, Xi hasn’t enacted deeper structural changes—such as asset disclosures—that experts in clean government say are needed to attack corruption at its root.

Xi seems to accept some levels of graft as an unavoidable consequence of sustaining one-party rule, some analysts say, whereby corruption is to be suppressed—rather than eradicated—through eternal vigilance.

For Xi, “it is all about attitude and mental disposition, not about institutional checks and balances,” according to Daniel Leese, a professor of Chinese history at the University of Freiburg.

Leese and other historians say Xi’s perpetual purges are inspired in part by Mao’s ideas on waging “continuous revolution,” which were meant to avert ideological atrophy in the party and broader society.

But whereas Mao roused ordinary Chinese into purging class enemies and assaulting what he saw as a decaying party from the outside, Xi has shaken up the party from within, using fear to enforce virtuous behavior. Even the party’s discipline inspectors themselves have become targets, under a rectification campaign launched in February that aims to “turn the blade inward and cut out decaying flesh.”

The point is to maintain constant pressure, according to Leese. “There is simply no way of reaching a final stop with this model,” he said.

While it has helped Xi accumulate a level of power unseen since Mao, party insiders say his “rule-by-fear” approach has stifled policy debate and fueled indecision among lower-level officials at a time when China requires more decisive leadership to deal with long-term challenges.

The fear is leading bureaucrats to act timidly, with potentially significant impact on the economy, researchers say. “Officials are more inclined to provide favors to [state-owned enterprises], thereby reducing their career risks because such allocations do not imply corruption,” Zeren Li and Songrui Liu, a pair of Chinese researchers, wrote in a recent study. Such favoritism undermines economic efficiency and diverts resources from more dynamic private enterprises, they argued.

Party authorities also have issued fresh warnings against “formalism,” or box-ticking behavior that cadres engage in to feign compliance with Beijing—bogging down the bureaucracy in unproductive work.

The persistent slowdown in China’s economy magnifies both the stakes and challenges for the party. Xi’s dominance “has made it difficult for lower officials to make decisions because they are concerned about running into trouble,” particularly given conflicting policy demands, said Andrew Collier, managing director of Orient Capital Research in Hong Kong. “They are at the difficult end of choices between paying for social services, economic development, and lowering debt levels—an impossible balancing act.”

Xi has signaled no retreat.

“The struggle against corruption will never end,” the Communist Party’s top antigraft body said in a recent commentary. “It will only be ongoing, but never completed.”

Write to Chun Han Wong at chunhan.wong@wsj.com