Doctors are rallying around an audacious goal: eliminating a cancer for the first time.

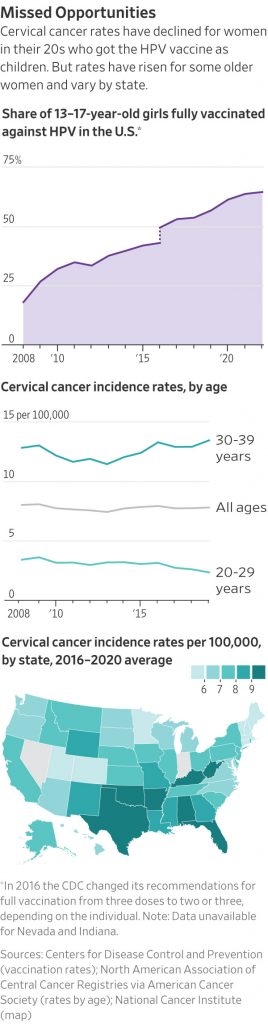

Cervical cancer rates in the U.S. have dropped by more than half since the 1970s. Pap tests enable doctors to purge precancerous cells, and a vaccine approved in 2006 has protected a generation of women against human papillomavirus, a sexually transmitted infection that causes more than 90% of cervical cancers.

With this evidence that the disease is preventable, groups that have worked for decades to end polio and malaria are turning to cervical cancer, plotting to take cases down to null. The World Health Organization is urging countries to boost vaccination, screening and treatment. Doctors in the U.S. are working on a national plan.

“We can eliminate a cancer for the first time ever,” said Debbie Saslow , a former American Cancer Society official who recently went to work for Merck, maker of the HPV vaccine Gardasil 9, which is the only one distributed in the U.S.

Now starts the last mile: targeting stubborn pockets of resistance and inadequate access to care that still result in deaths. HPV vaccination rates in the U.S. lag behind those for other shots. Screening rates also have fallen , and some women who do get screened and have abnormal results don’t return for treatment.

Cervical-cancer cases among women 30-44 rose nearly 2% annually from 2012-2019. Some 4,300 women will die of the disease in the U.S. this year.

Redoubled efforts

A proving ground for the elimination drive is Alabama, which has the nation’s fourth-highest cervical-cancer rate and worse numbers for Black women and women in rural areas. Health officials and doctors are aiming to wipe out cervical cancer in the state in a decade.

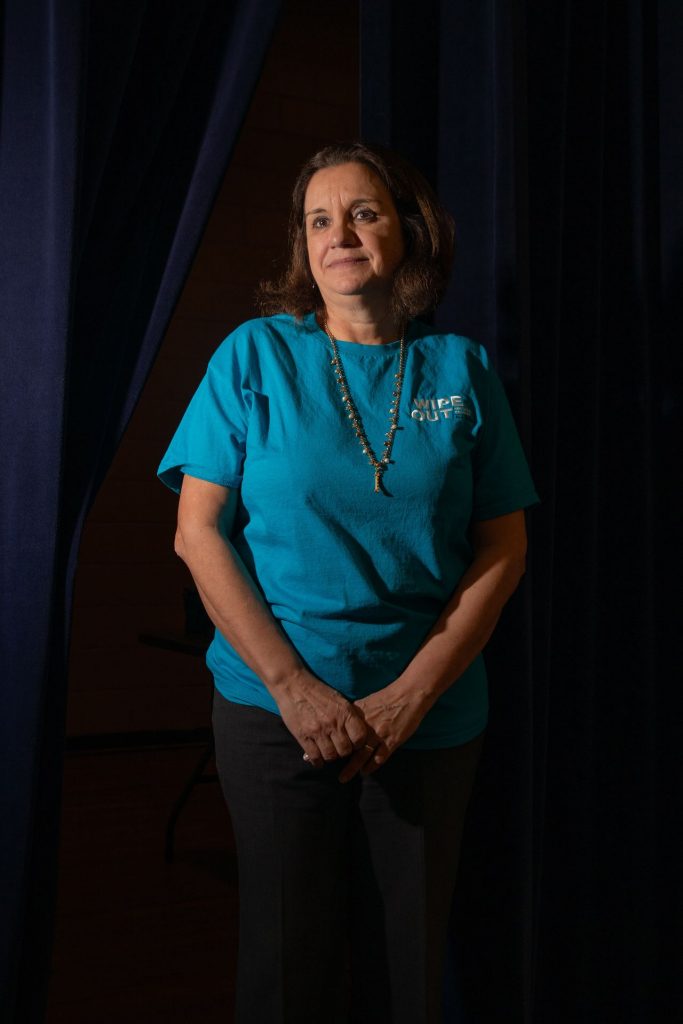

For Isabel Scarinci, the push to eliminate cervical cancer is personal. PHOTO: CHARITY RACHELLE FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Isabel Scarinci set out before sunrise in March for the 2½-hour drive from Birmingham to Chambers County, where cervical-cancer rates are more than four times higher than the WHO’s elimination target. Her aim was to vaccinate students at two schools.

For Scarinci, 61 years old, the push is personal. A polio infection as an infant in Brazil left her with a lifelong limp. She remembers her mother taking her door to door as a child, pleading with parents to get their children vaccinated .

In the decades since, the disease has come close to eradication. The last pockets of polio also have proved the toughest to stamp out, a reality Scarinci keeps in mind as she talks to school superintendents and women who didn’t know they were overdue for cervical-cancer screening.

“I’m going to work on this until the day I die,” said Scarinci, a behavioral scientist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “Because I know we can do it.”

Alabama hospitals are sending buses to screen women deep in the country, where gynecologists are scarce . Traveling nurse practitioners are examining women with abnormal results closer to home and without extra cost .

Scarinci and her colleagues vaccinated some 25 children between W.F. Burns Middle School and nearby Eastside Elementary School in eastern Alabama. As they packed up at W.F. Burns, a woman called to say she was rushing with her daughter to the school. They waited for her to race in, permission slip in hand. She held her daughter as she got her shot.

The turnout was lower than Scarinci had hoped. She and her colleagues planned to return to the schools this month.

“I’m not giving up,” Scarinci said.

Merck’s vaccine is approved for boys and girls as young as 9, but some parents don’t get it for their children because they worry about side effects or encouraging sexual activity. The shot doesn’t increase sexual behaviors and severe reactions are rare, studies show.

Tragic misses

Julianna Ferrone, 30, was eligible as a preteen for the vaccine. But her mother, Trish Swope, who survived cervical cancer herself, was worried about side effects, and Ferrone’s pediatricians pushed it off . When Ferrone sought the shot herself in her 20s, a doctor told her she was too old.

In 2020, her abdomen bloated and her pelvis pulsed with pain. Ferrone called a half-dozen clinics near her former home in Auburn, Ala. Three attributed her distress to irritable bowels or heavy periods. A doctor in Georgia finally gave her a Pap test. She had stage-3 cervical cancer. Ferrone credits him with saving her life.

Julianna Ferrone at home in Georgia with her mother, Trish Swope, who survived cervical cancer herself. PHOTO: AUDRA MELTON FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Swope said the news was harder to take than her own diagnosis. “I can’t help but feel like I failed her,” she said.

Ferrone underwent a hysterectomy in 2021, then chemotherapy and radiation. That kept the cancer at bay for almost a year.

Then it returned. She underwent chemotherapy again until last July. Today, she is cancer-free, beating low odds against a late-stage diagnosis with a disease she shouldn’t have gotten.

“Why is this still happening to so many people?” Ferrone said.

Write to Brianna Abbott at brianna.abbott@wsj.com