To Warner Bros., the Hollywood studio that brought Harry Potter to life in blockbuster movies and theme-park attractions around the world, J.K. Rowling may just as well have been wearing an invisibility cloak.

It was early 2022, and the Harry Potter author had avoided executives for more than two years. She’d recently skipped a reunion special that streamed on the company’s Max service, a notable absence amid the now-grown stars of the films. When she soon after attended the premiere of an installment in the spinoff “Fantastic Beasts” series, she didn’t pose for photos with the cast.

The stars who had embodied her iconic characters wanted little to do with her. Critics and former fans had spent the past two years castigating the author for public comments on gender and sex that they saw as attacks on transgender rights. When Warner didn’t rush to her defense, she felt betrayed by a company that had collected billions of dollars from her creation.

Then, like a letter arriving via owl post, word came that David Zaslav , the new chief executive of the studio’s parent company, Warner Bros. Discovery , wanted to try to repair the damage. Zaslav had started his new job when an associate told him to get on a plane to the U.K. if he wanted a chance at winning over the writer who controlled his company’s most valuable property.

Sitting across the table from one another at a London supper club soon after, Rowling and Zaslav spent four hours discussing their childhoods, their families, how they weathered Covid-19. Zaslav wanted to breathe new life into the Harry Potter franchise, seeing a new TV show as a potential tentpole in his streaming strategy. But he needed to use a light touch—this was about salvaging a relationship so complicated and emotional that many have described it not as a business partnership, but as a marriage.

“What was it like taking over this company?” Rowling asked him, according to a person familiar with the exchange. “What is your ambition?”

“A big part of it is you,” Zaslav replied.

Keeper of the keys

Over much of the past 25 years, J.K. Rowling held remarkable sway over the executive suite at Warner, which bought the rights to her fantasy series when she was an unknown writer. As Harry Potter’s popularity grew, Rowling’s power soared. Over time she exerted de facto control over the critical Warner asset, vetoing ideas, limiting its storytelling scope and issuing verdicts at biannual gatherings that Rowling referred to as “Ministry of Magic” meetings.

Executives flew across the Atlantic to charm her, or patch things up after a screaming match. For much of her partnership with Warner Bros., Rowling has largely kept her distance from the studio team, heightening an aura of impenetrability and suspicion. The few people who interact with her flex that closeness by calling her “Jo.”

The arrangement was tested time and again, but the results were undeniable, as Warner churned out one hit Potter movie after another for a decade, ending with 2011’s “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2.” More recently, a growing number of theme parks and other in-person attractions and a hit videogame have expanded the franchise’s presence around the world.

Now, Zaslav wants to write a new chapter in the once-in-a-generation franchise, in the hopes of sparking a magical turnaround in his company’s fortunes. Since taking over as CEO in April 2022, following the merger of WarnerMedia and Discovery , Zaslav has struggled to convince Wall Street that he can win in the cutthroat streaming business, where subscriber growth is anemic and profitability inconsistent. Warner shares are down nearly 65% since the merger. That includes a significant drop Friday, after the company reported lower revenue , a $400 million loss and fewer streaming subscribers in the U.S. and Canada.

Zaslav came to Hollywood presenting himself as a talent-friendly studio mogul. But he quickly made enemies. A cost-cutting campaign purged several TV series from the company’s streaming service and shelved movies like “Batgirl” and a new Looney Tunes feature before they had even aired. Partying with fellow millionaires at the Cannes Film Festival last May while picketing TV writers struck for better pay in Los Angeles didn’t help his case.

He can’t afford to alienate Rowling too. She is the last member of what was known internally at one time as Warner’s “A+ talent” crew, a group that included only two other members: Clint Eastwood and Steven Spielberg.

But now, Eastwood is 93 years old. Spielberg made his last two movies at other studios. Rowling appears to be the last one left.

This article is based on interviews with people familiar with Rowling’s relationship with Warner, including current and former employees of the entertainment giant and associates of the author.

A representative for Rowling said the author declined to comment. Her primary business partner, Neil Blair, said: “We pride ourselves on delivering best-in-class work for fans of the Harry Potter franchise globally. We hope under the new leadership at Warner Bros. Discovery that this will continue together, with the same care and excellence which the franchise has been synonymous with for over twenty-five years.”

The boy who lived

Warner Bros. was early to the Harry Potter phenomenon. The studio secured the rights to adapt the series after an eagle-eyed producer, David Heyman , read the unpublished manuscript of Rowling’s debut novel, released in the U.K. as “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.” Heyman took the idea to Warner Bros in early 1997.

Rowling wasn’t paid an impressive amount for the deal, whose terms gave the studio vast creative control over the property, reflecting her status as an unproven literary talent.

As millions soon came to learn, “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone” had been written by a single mom not far from welfare, stealing time to write while her baby slept by her side at Nicolsons, an Edinburgh cafe whose workers didn’t mind if she stretched a single cup of coffee for two hours.

By the time the third book, “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban,” was released in 1999, Pottermania was in full swing. The novels were bestsellers that inspired children’s names, tattoos and release parties flooded with young readers dressed in capes and glasses—fake scars scrawled on their foreheads. She not only got kids to read, she got them to line up for hours outside of bookstores for a chance to do so. The closest comparison many could find was Beatlemania.

That year, Rowling sat for an interview that would prove an early indication of the protectiveness with which she would guard her creation. It was with Lesley Stahl of “60 Minutes,” who explained how Rowling was turning down dozens of offers to license her characters to companies, from margarine producers to Boeing.

Toward the end of the interview, Stahl outlined a future where Harry Potter is in theaters, on TV and on toy shelves.

“I don’t know about the television series…,” Rowling said, shifting in her seat and growing uncomfortable. Action figures? She couldn’t hide her disgust at the thought.

“I’m a mother. I hate action figures,” she said, covering her mouth as though shocked at what’s coming out of it. “If the action figures are horrible, just tell the kids that I said, ‘Don’t buy them.’ ”

Then she added two words that would echo throughout studio halls in Los Angeles for years to come: “Sorry, Warners.”

Fantastic films and where to find them

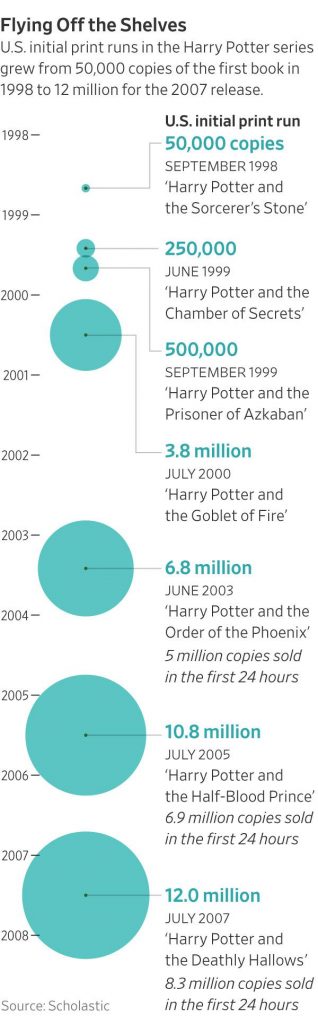

Over the next decade, Warner adapted Rowling’s Harry Potter books into eight movies. Seven of them are among the studio’s 25 highest-grossing films of all time. All told, the series collected nearly $8 billion at the global box office before ending in 2011.

But when Kevin Tsujihara took over as head of the Warner studio in 2013, he saw a franchise collecting dust, and had a challenge: What came next? Rowling had distanced herself from the studio, and Tsujihara flew to Scotland, where she lives, to reset the relationship.

Out of that rapprochement came an agreement to produce a new film series titled “Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them,” based on a spinoff book that takes place in the same wizarding world that Harry Potter lives in. Rowling, who had not adapted the Harry Potter books for the screen, wanted to write the Fantastic Beasts screenplays herself.

Tsujihara accelerated efforts to build a franchise team crossing film, consumer products, live attractions and other divisions, with one leader based in Los Angeles and another, per Rowling’s request, based in London.

A new enthusiasm infused the effort. Executives studied longstanding franchises to understand how a brand could become an “always-on” property.

George Lucas had allowed writers to expand the Star Wars universe with novels and TV series years after he’d finished directing the films. Jurassic Park and Batman have been revisited by different writers and directors time and again.

Harry Potter, by contrast, had a creator who didn’t want to lose any control.

No detail was too small. At one point, Rowling wrote executives to ask about the chocolate used to make “chocolate frogs”—a sweet featured in the books—that fans can buy at the parks. Why, she asked, was it not sourced fair-trade?

The incremental requests added up to significant contractual changes, turning a once-lopsided deal into one that granted her more rights and revenue as her stature grew. The new perks range from a bigger cut of merchandise sales to an understanding her team has influence over who on the Warner Bros. side manages the franchise.

Supporters say Rowling’s restraint has served her creation well. Harry Potter over the years avoided the franchise fatigue that would befall marquee Hollywood properties like Marvel and Star Wars, which lost some fans amid a glut of film and TV programming.

As Warner worked on Harry Potter’s next phase, executives had to rely on Blair, Rowling’s business partner, as the key liaison. A lawyer who had once worked for Warner, Blair had helped write her original contract. After that deal was signed, she hired him to run her business out of the U.K. He updated her on the studio’s ideas and pitches about once a month, visiting her home in Scotland, but Warner executives often felt left in the dark about what details he presented to her.

Most direct facetime with Rowling came at more infrequent Ministry of Magic meetings, held in London and New York. Warner employees would spend weeks preparing.

Inside the meetings, Rowling was often approachable and focused—one attendee noted that she never looked at her phone. But when things grew heated, over a contractual point or storytelling disagreement, the mood could get combustible. Screaming matches. Threats of boycotts. Tears.

Rowling often attached her personal history to the business at hand. At times she referred to her past as an abused woman, saying a group of men telling her what to do reminded her of her previous marriage, during which she has said her husband, Jorge Arantes, barred her from having her own house key and searched her handbag when she returned from trips out. (Arantes couldn’t be reached. In a 2020 interview with the British tabloid the Sun, he denied any “sustained abuse” in the relationship but admitted to slapping Rowling on the night she left him.)

At other times she invoked her time as a single mother, saying the characters under debate were like her children.

undefined Warner executives, certainly sympathetic to her history, didn’t know quite how to respond, and treated her as a de facto decider of matters large and small—even if, contractually, they didn’t have to.

They feared she would speak out if she disapproved of any Harry Potter item, discouraging millions of loyal fans from supporting it.

Around the studio, the refrain went: “We don’t want her to ‘60 Minutes’ us again.”

Wizards’ duel

The studio’s belief that Rowling should be the primary ambassador for the Harry Potter brand lasted for the first 21 years of the Warner Bros. relationship. Then, in 2019, Rowling found herself at odds with Warner Bros. employees and even some fans over comments she’d posted to Twitter concerning gender and sex.

Rowling had started by posting support of a London woman who had lost her job over what she called “gender critical” statements that included the belief that it is impossible to change one’s sex.

In Rowling’s view, the woman was simply standing up for the notion that “sex is real.” Six months later, Rowling mocked a newspaper headline for using the phrase, “people who menstruate.” She posted on Twitter: “I’m sure there used to be a word for these people. Someone help me out. Wumben? Wimpund? Woomud?”

Rowling, who had long publicly supported progressive candidates and repeatedly lampooned Donald Trump, became a world-famous enemy of some trans-rights advocates. Rowling responded to critics regularly, including in an extensive essay detailing the personal history that brought her to her stance.

“I refuse to bow down to a movement that I believe is doing demonstrable harm in seeking to erode ‘woman’ as a political and biological class,” she wrote. “I stand alongside the brave women and men, gay, straight and trans, who’re standing up for freedom of speech and thought, and for the rights and safety of some of the most vulnerable in our society.”

Rowling said she believed a vast majority of trans people did not pose any threat but that “any man who believes or feels he’s a woman” should not be permitted automatic access to bathrooms or shelters reserved for women.

Transgender advocates called her comments a “mountain of lies.” Fan sites dedicated to Harry Potter pledged to stop mentioning the woman who’d created the world they loved. Death threats against Rowling mounted.

Each time a new Rowling tweet about trans issues appeared, the Potter managers at Warner Bros. tried to work through their disappointment. Some agreed with her, others didn’t, but Rowling’s remarks threatened to drag an unimpeachable brand into a political maelstrom.

Executives began surveying the global fan base to anticipate how the author’s views might dent sales. The answer: not much. For the most part, Rowling’s statements had affected some peoples’ opinion of her , for good or ill, without having a material impact on the Harry Potter brand or business.

A smattering of Harry Potter fans claimed they would stop buying new books or products that put more money in Rowling’s pocket. But many responded like Aidan Stanley, a 26-year-old from Arizona first introduced to Harry Potter at age 4. He’s read the original seven books three times and plans a movie marathon each Christmas with his wife. Last year he played the latest Harry Potter videogame.

But Rowling? “She’s kind of whatever,” he said, speaking last month at the Wizarding World theme park in Southern California, clad in a Gryffindor robe and carrying his own wand. “I could not care less” about her comments, he said.

“I grew up with it, so I’m never going to be torn away from it.”

The Battle of Hogwarts

In June 2020, as the controversy reached a high pitch, Warner issued a statement: “We recognize our responsibility to foster empathy and advocate understanding of all communities and all people, particularly those we work with.”

Rowling wanted a stronger showing of support. Studio leaders felt they could not offer one without angering employees or other creative partners, such as the Wachowski sisters, trans women behind Warner’s Matrix series.

The core trio of actors in the Harry Potter films spoke out against her. Daniel Radcliffe, who’d portrayed the title character from ages 12 to 21, issued a statement soon after Rowling’s 2020 comments, saying: “Transgender women are women. Any statement to the contrary erases the identity and dignity of transgender people.”

An awkward family reunion neared. Warner’s streaming service, then called HBO Max, planned to stream a Harry Potter cast reunion in January 2022, gathering Radcliffe and other former students at the fictional Hogwarts School where the Potter series takes place.

Executives at Warner wondered how to involve Rowling. Some cast members didn’t want to see her, making one-on-one conversations between Rowling and an actor too risky to put on camera. Maybe she could narrate the special? Or appear by herself?

The problem was solved for them when word came that Rowling wanted no involvement at all in the reunion. The team behind the special was relieved.

The Chamber of Secrets

While Rowling’s relations with the Harry Potter actors frayed, Warner executives continued to pursue what had become a yearslong quest: getting a Harry Potter TV show made.

Franchise executives tried to get creative, at one point pitching her team on a stop-motion animation version of Harry Potter.

Warner executives watched in frustration as competing streaming services took off, and established franchises such as Star Wars and DC Comics became treasure maps full of potential shows.

Around three years ago, before Zaslav took over, the studio approached TV writers and asked them to brainstorm ideas in the Harry Potter universe. A prequel about the generation of wizards that included Harry’s parents was one idea. A look at a different school for young wizards was another.

The ideas weren’t presented to Rowling. Warner executives knew she had the right to kill the projects should she choose to do so.

That veto power stemmed from Rowling’s request in the early 2000s to grant her authority over “non-author written sequels,” legalese for the kind of prequels and spinoffs that the studio wanted to explore with writers other than Rowling.

The issue eventually landed on the desk of Warner’s top executives. The verdict: Rowling could have the rights for her lifetime. But that too was eventually amended at the request of Rowling’s team, so that the rights will be controlled by a literary trust when she dies, giving a representative of the author veto power in perpetuity.

Reparo

When Zaslav was named CEO of Warner Bros. Discovery in 2022, he gathered his deputies and through “sheer force of will” mandated a renewed effort among his lieutenants to get Harry Potter onto TV, recalled Casey Bloys, chairman and CEO of the company’s HBO and Max content divisions.

“Not, ‘What would you do if…’ ” Bloys said. “But, ‘We’re going to make this happen.’ ”

Warner’s HBO has a rich heritage of producing hits dating back decades, from “The Sopranos” and “Sex and the City” to “Game of Thrones” and “Succession.” Zaslav’s task: building Max into a brand of its own by bringing a new wave of must-see shows to the streaming service, while holding down costs and delivering the profits investors crave.

A Potter series would be costly, but could prove a major subscriber draw. Zaslav soon concluded, however, that the only Potter show Warner could legally pursue without Rowling’s permission was one that stuck to the stories of the original seven books, since those were firmly in the studio’s control and not the kind of prequel or spinoff she’d clawed back the rights to years earlier.

When Zaslav met with Rowling following her months of anger toward Warner Bros., he knew he was on strong footing to create a TV remake of the books, but he still wanted her on board.

“It’s just not a great creative move to have the architect unhappy,” said Bloys.

Months of talks followed as Zaslav spoke to Rowling directly. The studio pitched Rowling on the big-budget treatment that TV can afford now, in a market where per-episode costs routinely exceed $20 million. There was also the chance, through a show likely to premiere more than 20 years after the first movie, to use the series to hook younger audiences on the wizarding world.

The new series will bring to the screen subplots and tertiary characters who didn’t make the cut in the eight movies. A single season may cost up to $250 million, a reflection of the kind of cinematic, high-budget production now expected by fans in TV’s prestige era.

“Max’s commitment to preserving the integrity of my books is important to me,” said Rowling in a statement when the show was announced last April.

Max executives are meeting with writers now to hear how they would approach the TV series, Bloys said, with a small group pitching Rowling on the concepts.

When the show was announced, Rowling responded on X to disaffected fans who said they’d boycott the series because of her involvement.

“Activists in my mentions are trying to organise yet another boycott of my work,” she wrote. “As forewarned is forearmed, I’ve taken the precaution of laying in a large stock of champagne.”

Mischief managed

Zaslav has a series in development that he says will debut in 2026—and that means he has gotten a Harry Potter TV project closer to the finish line than any of his predecessors did in years of trying. Behind the thawing relations, executives say, is a shift in the studio’s approach—one that seeks to avoid alienating the Rowling camp without automatically ceding power to it either.

Billions of dollars in investment are now coming to fruition, after years of negotiation to get the author on board.

Potter theme parks and live attractions have hit nearly every country where research has revealed a high concentration of fans. A new offering just went up in Cologne, Germany, and Abu Dhabi is on the docket. Potter attractions in the U.S.—built at Universal-owned properties as part of a deal with that company—have boosted attendance at theme parks in Orlando, Fla., and Southern California.

The parks are built around the stories in Rowling’s original series, putting their development in the purview of her original contract with the studio. Behind each development, executives say, is an expectation she and her team will have signoff on matters large and small.

In Tokyo, fans buy trunks that look ready for boarding at Platform 9¾, used by young wizards to ride the train to Hogwarts. Hufflepuff cardigans ($90) and personalized wands ($79) can complete the look.

“The closer you can get people to touch and feel, the more success you can have,” said Simon Robinson, Warner Bros. Discovery Studios’ chief operating officer.

Another lucrative part of the franchise is the blockbuster “Hogwarts Legacy” videogame, the bestselling title of 2023, with more than 24 million copies sold, generating more than $1 billion in revenue. The game’s performance—especially coming after Rowling’s tweets—reminded executives anew of the cash machine the author’s creation remains.

For years, Rowling eschewed some mobile-game ideas, worried that her characters could be used in ways that might exploit children and get them to spend their parents’ money without permission. But mobile games such as “Magic Awakened,” which allows players to role-play as new Hogwarts students, eventually made it to market.

The division overall has enjoyed greater flexibility than its film and TV counterparts.

“Hogwarts Legacy,” for instance, had a notable element: It didn’t feature Harry Potter. Instead the game takes place in the 1800s, with allusions to characters who readers would know but with a kind of literary distance that gave its designers storytelling license.

A videogame based on the Hogwarts game of Quidditch is among the next projects, after engineers overcame an early snag. Building the game, they realized systems wouldn’t run as smoothly if they featured seven players on each Quidditch team, as portrayed in the book.

Reducing the number of players on a team, though, contradicted Harry Potter lore.

Rowling allowed it. The game is now in development.

Write to Erich Schwartzel at erich.schwartzel@wsj.com