Hundreds of businesses have volunteered to measure and report their impact on the natural world, as they recognize the growing risks to their own operations from environmental degradation, including a denuded Amazon rainforest and dying coral reefs.

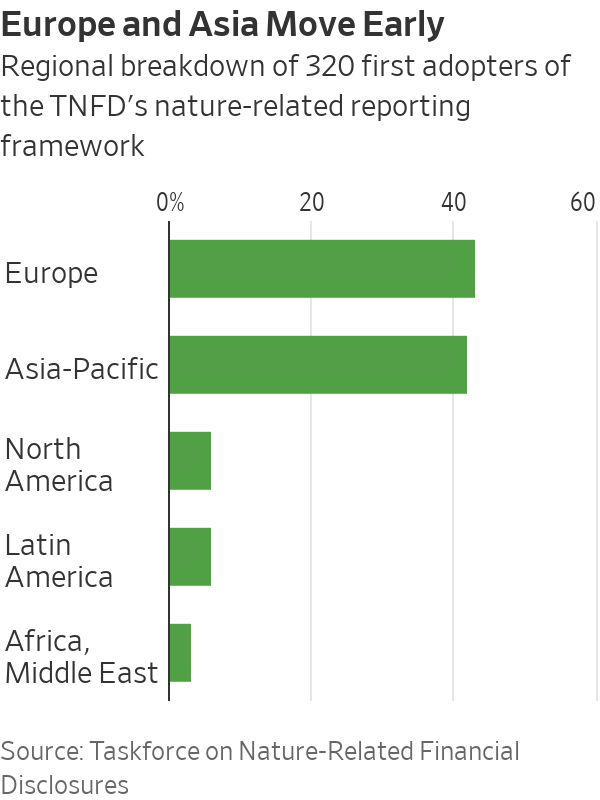

While many businesses are struggling to meet coming requirements to report their climate impact, more than 300 banks and companies are pledging to go much further. Early movers from across sectors and countries have promised to regularly publish nature-impact information as set out by the Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures, or TNFD, a United Nations-backed initiative.

The first adopters represent $4 trillion in market capitalization and around $14 trillion in assets under management. They include seven of the world’s 29 globally systemic banks, Japanese investor SoftBank, Norway’s sovereign-wealth fund, Gucci parent Kering, miner Anglo American and pharmaceutical majors GSK, AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk.

Take-up by sector leaders should encourage peers to accelerate their efforts, said Tony Goldner, executive director of the TNFD. The framework is aligned to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework agreed to in 2022 by nearly 200 countries. It recommends disclosures in governance, strategy, risk and impact management, as well as sector-specific metrics and targets for reducing impact.

Biodiversity impact is both a new type of risk and a new opportunity, said Valentin Alfaya, sustainability director at Spanish-listed infrastructure group Ferrovial, one of the first movers. “As a consequence of the implementation of the TNFD and our own natural capital assessment program, sometimes investments are going to be left aside,” Alfaya said.

“When you are interacting with those protected areas that are very relevant in terms of ecological value…it’s really risky for the company, not just in terms of reputation but also in terms of operations and even finance,” he said.

Using the framework will guide investment and help integrate nature into financial decision making, said Marisa Drew, chief sustainability officer at lender Standard Chartered. The move is a “significant opportunity for us to facilitate financial flows toward nature-positive outcomes,” Drew said.

Gauging impact is central to business decisions and managing risk, said Jennifer Motles, chief sustainability officer at tobacco giant Philip Morris International. “The TNFD recommendations and guidance will support us as we continue to focus on nature-related dependencies, impacts, risks, and opportunities,” Motles said.

The ramp-up in disclosure comes amid heightened awareness of the threat posed to the world by such natural degradation. The top four medium-term risks are all environmental, according to the World Economic Forum’s global risk report published earlier this month. They include extreme weather events, critical changes to the Earth’s systems, a collapse of the ecosystem and natural-resource shortages. “The collective ability to adapt to these impacts may be overwhelmed,” the report warns.

The World Bank estimates that the global economy could lose $2.7 trillion by 2030—which would mean a 10% drop, on average, in the economic output produced across all nations—if certain at-risk ecosystems collapse, such as fisheries or pollination by bees.

Adoption of the TNFD is “a clear signal that investors, lenders, insurers and companies are recognizing that their business models and portfolios are highly dependent on both nature and climate,” the taskforce’s co-chair, David Craig, said. Natural risk should be treated both as a strategic risk and an investment opportunity, Craig said.

But reporting the damage done to the natural world isn’t the same as stopping it, said John Tobin-de la Puente, a professor of corporate sustainability at Cornell University. Disclosure is less about encouraging companies to change than it is about giving investors clear information on risk, he said.

Unlike carbon emissions, which can be assessed in terms of metric tons, there isn’t consensus on how to gauge environmental impact—whether, for example, in terms of protected species, general biodiversity, or a bundle of measures, said Tobin, a tropical ecologist and corporate lawyer by training. Some efforts have been made to create units of ecosystem impact, but for now, no universal metric exists, he said.

Alternatives to current business models will also need to be created, just as renewable energy has been developed to replace fossil fuels, Tobin said. “Will we get there at some point soon, before it’s too late for the biosphere?” he asked. “That question is still open.”

Write to Joshua Kirby at joshua.kirby@wsj.com