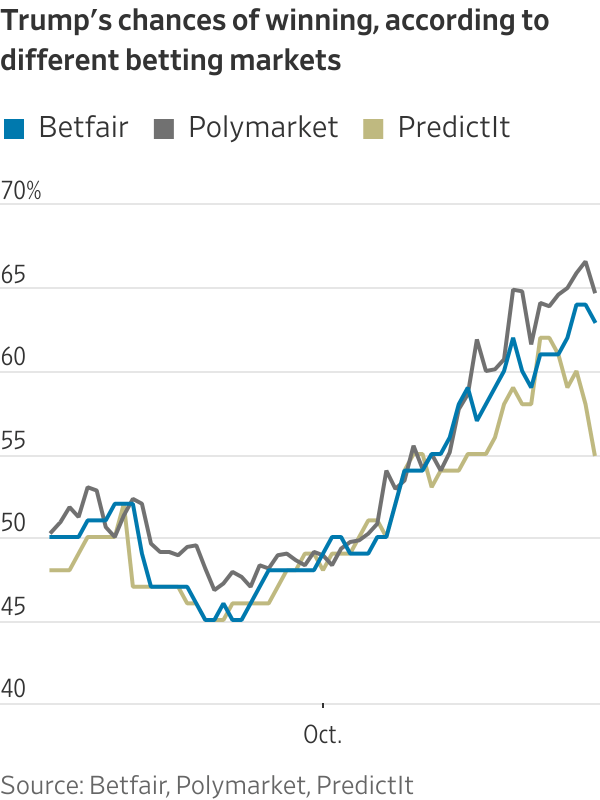

Betting markets show former President Donald Trump has a roughly 60% chance of beating Vice President Kamala Harris next week. Should they be trusted?

History suggests that betting markets have generally been good forecasters of U.S. elections. More often than not, the presidential candidate with the best odds before Election Day goes on to take the White House.

But there have been some glaring exceptions. In 2016, for instance, betting markets such as PredictIt and U.K.-based Betfair gave Hillary Clinton a more than 80% chance of defeating Trump in the days before the election. Instead, Trump won an upset victory.

Today, with polls showing Harris and Trump in a dead heat, the accuracy of betting markets has become a politically loaded question. Supporters of Harris have raised doubts about a recent run-up in Trump’s chances, arguing that betting markets are vulnerable to manipulation, skewed to a right-leaning user base and distorted by multimillion-dollar wagers placed by a small number of users. Meanwhile, Trump supporters say the betting markets are reacting to polls tightening in his favor and signs of Harris losing momentum in the campaign’s closing stretch.

Many of the biggest betting markets, such as Polymarket, don’t allow wagers by Americans. But a recent federal court ruling legalized election betting on regulated U.S. markets. The ruling set off a scramble as brokerages and trading startups enabled bets on the Trump-Harris race and launched a marketing blitz to juice customer interest before the election.

Betting on U.S. elections was common during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, before the rise of modern polling, and newspapers reported the odds for a Democratic or Republican victory in much the same way they report poll results today.

“Betting odds are generally taken as the best indicator of probable results in presidential campaigns,” The Wall Street Journal wrote in 1924. The era’s big betting firms dispatched men to attend candidates’ speeches and send back “unbiased reports of the psychological reaction of the audience,” helping the firms determine the odds they quoted to their customers, the Journal wrote. Banks relied on such firms for daily updates on election-betting trends.

In the 15 elections between 1884 and 1940, the candidate with the best odds as of mid-October won 11 times, and only once did the unfavored candidate pull off an upset, according to a 2004 study by economists Paul Rhode and Koleman Strumpf. In the other three elections from that period, the odds were essentially even and the races very close, according to the study.

Election betting declined after 1940, pressured by state antigambling laws and supplanted by the rise of scientific pollsters such as Gallup, the study found. Polls became the preferred method for the media to track elections.

In the 1948 election, pollsters got it wrong when they forecast a loss by President Harry Truman , famously leading the Chicago Daily Tribune to print the erroneous front-page headline “Dewey Defeats Truman.” What is less well-known is that betting markets got it wrong, too. Most bookmakers gave Truman a roughly 11% chance of winning in the weeks before the election, according to Strumpf, who is now a professor at Wake Forest University.

Starting in the 1980s, economists popularized the idea of using “prediction markets”—a more reputable term for betting markets—to assess probabilities of future events. A variety of online betting sites emerged, such as the Iowa Electronic Markets and Dublin-based Intrade, with boosters saying that they harnessed the wisdom of the crowd to predict the future.

Such sites struggled to gain scale and lasting traction, in part because of resistance from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. The CFTC pushed them to either accept stringent limits or block access to Americans so they wouldn’t be subject to U.S. regulation.

Still, they notched some successes in forecasting elections. In the closing months of the 2008 election, bettors on Intrade correctly anticipated that Barack Obama would beat John McCain, with Obama’s odds skyrocketing after the financial crisis began that September. In 2012, Intrade put Obama’s probability of winning re-election at mostly 60% or higher from September onward, according to data provided by David Rothschild, an economist with Microsoft Research. Intrade shut down in 2013.

Today’s prediction markets have seized on skepticism of opinion polls to argue that betting markets are a more accurate predictor of election results. Not only did pollsters miss badly in 2016, they have suffered from the growing difficulty of gathering information , as fewer Americans use landline telephones and many don’t answer calls from strangers.

“We believe Polymarket is the most accurate way to follow the election,” Polymarket founder and Chief Executive Officer Shayne Coplan said in an interview over the summer. “Nobody takes polling seriously anymore.”

In 2020, prediction markets gave Joe Biden lower chances of winning than polls implied—and their skepticism turned out to be prescient when Biden didn’t crush Trump in a landslide. At the end of October 2020, for instance, bettors on PredictIt were giving Biden a 65% chance of winning, while FiveThirtyEight’s poll-based statistical model put his chances at 89%.

But betting markets missed in 2022. Just before Election Day, PredictIt was giving Republicans a more than 70% chance of taking the Senate, reflecting media narratives of a “red wave” election. The Democrats ended up flipping a seat to win a narrow 51-49 majority.

Write to Alexander Osipovich at alexo@wsj.com